This treatment of modality and language as in themselves producing specific effects is encouraged by the prefix “multi-.” The term “multimodality” suggests an array of discrete modalities which one can then choose from among (viewed as resources), just as the term “multilingualism” suggests an array of discrete languages which one can then choose from among, switch between, or even “mesh.” Distinctions among these various “modes” and “languages” don’t hold up under scrutiny. Absent such scrutiny, there is a slippage between “modality” and “medium” (following the notion of “multimedia”) that leads to restricting understanding of the experience with a particular technological medium to a particular sense (say, printed text understood as associated with the visual).

That slippage overlooks the necessary labor of readers/viewers/listeners in their encounters with a particular medium and, more broadly, traditions of reading/viewing/listening practices, and the ultimate inextricability of the senses as they work and rework (with/on) particular modes and media, whether printed alphabetic words, film, audiotape, dance, f2f speech.

In other words, dominant understandings about the traditions of engaging with specific media and modes (for instance, that one approaches speech [and music] only as an aural/acoustic phenomenon, vs. also always simultaneously as visual and tactile, say) abstract from the complex of the experience/event. They yield a highly reduced understanding of the “mode of production” (to invoke a different sense of “mode”). This limited understanding in turn encourages the danger of treating modes and media and languages as an array of discrete resources rather than acknowledging the plurality of interactions and relationships present in the complex production of languages/language media/modes. 16

Labor, Sense 2: Resistance to Moving beyond SL/MN

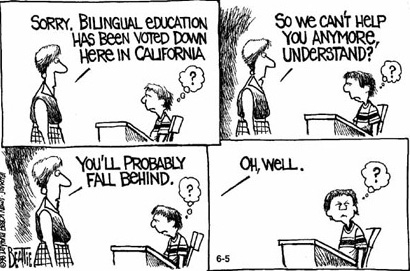

There may be a parallel between the resistance folks have to the idea of learning new media and the resistance they have to the idea of moving beyond monolingualism. While it’s tempting to dismiss this resistance as a manifestation of adherence to SL/MN ideology (and while often enough that may well be the case), we need to attend to the work necessary to such shifts in practices and perspective. These are not simply beliefs to be shucked off, but shifts in material social practice that require not only access to hardware, say, but also time, effort, training, and so on. 17

However, part of the problem here may be that what seems to be demanded is more than what is actually being demanded: conventional definitions of multilingualism, for example, seem to demand that individuals develop a putative “native-like” fluency in more than one language (see Horner, Donahue, & NeCamp, 2011). Dominant understandings of language competence as an individual achievement of mastery of a “target” language, and the myth of native-speaker fluency (as if all speakers of a given language have identical fluency in all aspects of that language), then lead people to feel personally defective for failing to achieve native fluency in more than one language (or even one language) and to imagine that what seems to be asked of them is far more lofty and unreachable than it actually is.

We suspect a parallel/coterminous debilitating belief about communicative competence may be operating in people's resistance when they are confronted by demands to be “fluent” in seemingly “new” modalities and communication media. So how do we introduce and advance an alternative and more capacious view of competence in our work with our colleagues and students (e.g., one that locates competence as an ongoing and collaborative achievement)? This question, of course, leads us directly to matters of pedagogy.

See also my metacommentary entry on page two.

See also my metacommentary entry on page two.

Beethoven’s Hammerklavier sonata (opus 106) exploits the extended range of volume that the “hammerklavier” offered in comparison to the harpsichord. In saying this, I am of course potentially shaping the listening practices of those hearing and seeing the performance of that sonata in the clip.

Beethoven’s Hammerklavier sonata (opus 106) exploits the extended range of volume that the “hammerklavier” offered in comparison to the harpsichord. In saying this, I am of course potentially shaping the listening practices of those hearing and seeing the performance of that sonata in the clip.