What gave T.J. Lane, for instance, the idea to walk into a public high school in Chardon, Ohio, in February 2012 and begin shooting his peers is not very mysterious. Half a century of public gun violence in schools and other public spaces has provided copious examples for imitation. But what gave Charles Whitman the idea to go to the top of the University of Texas Tower in 1966 and kill fourteen people remains at least somewhat mysterious. He had no historical precedent to mime. Did he have a fictional one? How did he get from Point A to Point B? For now, hold in memory this central question -- what caused Charles Whitman to see the UT Tower as a sniper platform -- under the topos "Charles Whitman and the Whiteness of the Whale."[3 ]

Despite renewed attention to topical invention systems from rhetorical scholars of both writing and speech, the spaces between the places -- between Point A and Point B -- have received relatively little notice. Topoi came to rhetorical invention through the ancient Greeks. In the rhetorical turn of the mid-twentieth century, Chaim Perelman and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca, following Cicero and Quintilian, went Latin-ward and called the places of invention loci. Topoi or loci, topical invention systems are central to all periods of rhetorical theory and practice. Topos or locus singular; topoi or loci plural. Tower is a topos; sniper perch is a topos. Coordinate the two with a linking verb -- "the Tower is a sniper perch" -- and you have a definitional claim. Whether we stop to reflect on it or not, we human creatures use topoi -- literal and/or figurative places of memory, invention, and reinvention -- in every thought and utterance we generate, awake or asleep, every moment of our lives -- for we are always somewhere, until we are not. Topoi govern what we think, what we speak, and what we remember; topoi govern but do not determine. For one who has become native to a place (Jackson), a topos can be architectonic: a fundament. And topoi recollected allow for the possibility of reinvention. Further, topoi generated and suffered by humans are located in time as well as in regions: time-spaces span the places and generate ratios between. Despite the power of the kairic now, the most fundamental of these in-between spaces is chronological time -- khronos -- itself, as Mikhail Bakhtin suggested with his synthetic idea of chronotopes.

Bakhtin, a Russian scholar whose work on the social contexts and consequences of the European novel was repressed by Soviet officials through the mid-1960s, held that all language is dialogic: utterances are always responses, always in dialogue with other utterances. Further, Bakhtin argued, tyrannies attempt to destroy the dialogic nature of language by communicating through single-voiced monologues of absolute authority -- a view encouraged at least in part by Bakhtin's experience of forced internal exile for his writings. Further, several of Bakhtin's friends and colleagues were "disappeared" for their intellectual work. In contrast to monologic authoritarianism, Bakhtin described an imagination he called "chronotopic," a visualization of time and space in which the two collapse. "Time and space merge ... into an inseparable unity,” Bakhtin wrote. “A definite and absolutely concrete locality serves as the starting point for the creative imagination." Bakhtin argued that chronotopic imagination unites the present, the past, and the future to aid reinvention and thus keep vital the possibility, even in politically repressive contexts, for change.

In addition to time and space, cause -- the how(l) -- is another way of getting from Point A to Point B. Cause is a time-laden path strewn with posts and propters, source of innumerable fallacies and false conflations with correlation. This chapter focuses on the spaces between the places and pauses to consider how ratios of rhetorical influence -- spaces between here and there, between Point A and Point B -- accidentally and by design provide resources for invention, reinvention, and, perhaps, intervention (Atwill). For words are no transparent medium through which thoughts pass unsullied. Though the danger of a single narrative is clear, multiplicities of conjectures and causes bring their own kind of entropic peril when the need is to know -- or to do.

In their volume The Effects of Rhetoric and the Rhetoric of Effects, editors Amos Kiewe and Davis Houck and their impressive stable of authors contribute to a timely reexamination of “effect” in rhetorical criticism. While the book is indispensable to any scholar needing a snapshot of the state of the art on rhetorical criticism about effect in the communication tradition, the book lacks, beyond a mention or two of composition studies and literary criticism, any account of work in interdisciplinary rhetorical studies that traverses similar territory. Unfortunately, like some of Roderick P. Hart’s work (3-4), Kiewe and Houck’s volume reinscribes Aristotle’s exception-that-proves-the-rule divorce of rhetoric from poetics in a way that keeps the volume from looking at how stories and practices of all kinds exert rhetorical influence on values and actions.

The Rhetorical Influence of Austins

The Texas Observer had an official office dog: Mine. Her name was "Shit.” I always wanted a dog with that name, so I could go out back and scream "Shit!" whenever the occasion called for it.

− Molly Ivins, quoted in Red Hot PatriotDriving north across the Mason-Dixon on my way back from D.C. in early March several years ago, I stopped to visit my parents' graves. It had been a year or two, and it felt like time. Austin Austin Austin Austin. Dallas. Dallastown.

I got to Blymire's cemetery, just outside my hometown of Dallastown, Pennsylvania, saw the 1855 church where one of my nieces was married, and behind the church, the gravestone with my last name on it. I parked, walked over to the place where my name was, careful to tiptoe between, rather than on top of, the graves, like a good funeral director's daughter.

I saw the gravemarker of "Rosa B.," my grandmother. Then I was startled to see, dropped over the "Austin H., 1915 to 1998," two berry-seed-laden droppings. Cat shit. On my father's grave marker. Without a thought, I pushed the excrement off my father's first name with my shoe -- the droppings had been there for a while and so neither stuck nor stained -- and then realized that, from this place, this point, this distance, this far after March 15, 1998, this act was the only act of care possible. I then righted the little flag that my sister Sarah Jane had placed there the previous fall for Veterans Day. Weird to care for one's father, arguably, thirteen years after he died. That's when the tears came: the coldness of cleaning off the stone with my shoe compared to my small victories of wringing warmth from him across the years.

"Memory believes before knowing remembers." Like so many other sentences from William Faulkner, that one, from his novel Light In August, regularly bounces through the echo chamber of my head. My cousin David and I were upstairs with the bedroom door closed. He was on his back with his knees bent and his feet pointed toward the far corner of the ceiling. He told me to sit on his feet, and I did, and he propelled me through the air. I landed with a lardy thud, and we laughed and laughed and laughed. Thunder started from below. Loud footsteps. More thunder. "What bumped?" my father roared. Loud footsteps closer. I don't remember anything else.

Sixth Marine Division. My father served in the South Pacific during World War II. He lost much of his hearing from sleeping on wet ground. His first wife died, and the Marine Corps wouldn't let him come home for her funeral. What bumped? It was not until I began to bring friends home from college and had to offer some context about who my father was that I realized through speech that my father -- my first Austin -- had been first a butcher, then a Marine, and finally a funeral director. War always comes home. Even when the soldiers, alas, do not.

As I stood in the cemetery looking at the leavings, I remembered one of my father's favorite phrases: "Mean as cat shit." Thus the tears troped away. Inuits have scores of words for “snow”; Pennsylvania Welsh Germans can say and do a myriad of “mean.”

Austin. Austin H. Eberly. The Austin H. Eberly Home for Funerals. It was my father's role as a public man in small-town Pennsylvania that made me so interested in publics theory in graduate school: in the ratios -- the spaces between -- public ethos and private pathos. In particular, social psychologist Richard Sennett's book The Fall of Public Man helped me understand that I needed to balance my father's often inconsiderate behavior at home -- I here enjoy the relative comfort of euphemism -- with the public role that he played not only in his business but in Dallastown. I recollect too that when he retired he had on the books the funeral expenses for several families in our town, costs he covered when the families could not or would not pay. I too recall the volunteer ambulance service he offered to the community for decades. Likely for legal reasons the ambulance was called an "invalid coach," the phrase fuel for the ear-engines of a child with language obsessed.

I have thought often about the stories he did and didn't tell: the bodies he scraped off highways, the maggots -- he would sometimes talk about this at dinner -- he had to remove. It is only recently -- after being with several creatures as they make the transition from animated to what-we-do-not-know -- that I have begun to reflect on the situations he may have encountered when he walked into the homes of the very recently deceased. Among my earliest aural memories are of Dad on the phone, reading obits out loud to the newspapers.

Once in high school when I was complaining about how my father wouldn't let me travel to Bermuda with the high school band -- I was the only one not allowed to go, "because of the Bermuda triangle" -- my friend Cary gave me a glimpse of my father I knew I'd likely never see. Cary's uncle had died many years earlier in a swimming accident, and Cary's family -- according to Cary -- talked about not only how my father consoled the family but also how he told stories about the uncle, stories that made grieving people feel better and helped them to begin to attempt to smile and laugh again. While Dallastown was too small for many of us to dwell collaboratively outside the bonds of family and friends, as Sennett says is necessary for public life, it was clear to me that Cary's story reflected a realm of action separate from how my father lived, at least in my experience, in the privacy of his home.

Then one day I met Mr. Love at Market. My dad graduated from high school in 1933, at the height of what would come to be called "The Great Depression." He and his father, who I never knew, butchered animals and peddled meat around Dallastown. They also had a stand at one of York's farmers’ markets. Many times I had gone to York's sprawling Central Market wondering where the Eberly's Meats corner stand had been -- but for one reason or another never getting a satisfactory answer. One day during the summer after my eldest sister passed away, I found myself driving around downtown York, hungry for lunch. I realized the red light where I sat was a few blocks from Penn Street and another of York's markets, which was open the days Central Market was closed. I walked in, a bit delighted with myself that I had thought of stopping at an urban farmers’ market, and found the nearest stall inhabited by two lean, ebony merchants selling mango and black bean salsa beside fruit smoothies. I ordered a smoothie and waited, appreciating York's diversity and how what was for sale had over the last decade become more healthy than potato chips and whoopie pies. While I waited, enthused, the merchant asked a man walking past if he wanted to try the salsa. "I've tried it, and it's great," I turned around and, beaming, found myself saying to a man who looked a lot like me: puffy and white, unlikely to stop at this particular counter.

"Sure. I'll have a taste," the man said. And he ended up ordering something. And so we waited together. The name of the stand was "Simply Mixed."

Small talk turned biographical. "I'm from Dallastown. Rosa Eberly," I said, offering my hand, as women still really aren't supposed to do where I come from. He shook my hand and said his name. What I remember is that his last name was Love.

"Are you Austin Eberly's daughter?" he asked, looking surprised.

"Yes I am. Did you know him?"

Mr. Love hesitated. "I'll tell you what," he said. "Your dad was tough. He was a perfectionist. And he demanded perfection from everyone around him.”

"Yep," he concluded, "your dad was tough."

Suffice it to say that his name was Austin. And my brother's name is Austin. And my nephew's name is Austin. And then there is the Austin where I lived for eight years. Austin as topos. Point A, Point B. Moving back home, I have learned, will not bring your parents back to life.

The Austin H. Eberly Home for Funerals, 104 W. Main St., Dallastown, Pennsylvania, is where I lived for the first several years of my life, in the apartment above the funeral home. My dad and my brother used to shoot from the dining room window pigeons off the roof of the Lutheran church next door. The embalming room was below the bedroom where my three siblings and I slept.

When I was three, my hometown turned 100. My first memory is of the day President Johnson visited for the centennial parade: September 3, 1966. He gave a speech at the post office. We were not allowed to go. Austin Austin Austin Austin: Dallas, Dallastown.

I could find no documents in the LBJ Library indicating with certainty why the president was attracted to visiting a tiny Pennsylvania town called "Dallastown." However, I can imagine two reasons: Johnson's retreats from Washington, D. C., in the Summer of 1966 were part of an effort to move the national mind away from the escalating disaster that was becoming the US presence in Vietnam. News stories about a town called "Dallastown" might have helped to reframe the Dallas topos after the assassination of President Kennedy in that Texas city two and a half years earlier. Unlikely. But imaginable.

September 5, 1966. The centennial parade. People couldn't stop talking about the snipers on the roof of Dr. Piper's house across Main Street from the funeral home -- and up the street, on top of the American Legion.

The Open Square: War Always Comes Home

Five weeks -- 34 days -- before President Johnson rolled slowly by my father's funeral home, some towheaded three-year-old me standing beside a veteran of the Spanish-American War in his wheelchair, watching dark-suited men seeming to float on the four finned corners of the black, gleaming presidential limo, Charles Whitman took an elevator to the top of the University of Texas Tower and, after killing his wife and mother, in his words to "spare them the embarrassment," beat a receptionist to death with the barrel of a rifle and then shot nearly fifty people, killing another 14 over 90 minutes. That's why there were snipers on Dr. Piper's roof and on top of the American Legion. SWAT teams being born.

The shooting and killing parts of gun stories tend to get told -- at least the shooters' stories, if much less often the victims'. The shooting and killing part of Charles Whitman's story, in different forms and through countless cultural allusions, has been told. A Whitman -- that’s Charles, not Walt -- a Whitman story that has not been told, though it merits a brief dismissal in Gary M. Lavergne’s comprehensive “true crime” account of Whitman's life and the shootings, A Sniper in the Tower: The Charles Whitman Murders, is that of Ford Clark's 1962 Fawcett Gold Medal novel The Open Square. "Gold Medal," let me assure you, is a brand and not an award.

The Open Square is, in part, a novel about an unhappy and aggrieved undergraduate male who goes to the top of a university administration building -- a dome with a tower atop it, very likely set in Iowa City, near where the author lived -- and shoots people, turning the university and capital city into a war zone. However, the “bell tower boy” plot is in many ways subordinated to the other central plot of the novel: a homophobic, bodice-ripping celebration of heteropatriarchy and rape culture. Sometimes you can judge a book by its cover: The Open Square advertises itself as “A stark, penetrating novel of a man who tried to win power by pawning his wife’s body -- and a boy who tried to win glory with a rifle in his hands and a whole town prostrate at his feet.” Harry Keeler, the city manager, is the alleged wife-pawner, and Ted Weekes is “the boy in the tower with a rifle.” The two other main characters are Police Chief Ashton and Elaine, once Keeler’s wife but -- in the novel’s present tense -- now Ashton’s.

The Open Square is also trite, misogynist, and quite possibly just the kind of puerile, macho crap that would influence the imagination of a dysphoric, amphetamine-eating late adolescent Marine sharpshooter -- that is, Charles Whitman. About any possible influence of The Open Square on Whitman's actions, Lavergne concludes, "No evidence was ever uncovered that Charles Whitman might have read the book, by checking it out from a library for instance, or even that he might have known such a book existed" (276). In what Lavergne describes as "a haunting coincidence" (275), the boy in the tower in The Open Square climbs a tall building on a university campus somewhere in the Midwest and begins firing a high-powered rifle at students, faculty, and townspeople below. Lavergne writes that "clear evidence does exist that Whitman had immediately recognized the value of the Tower as a fortress the first time he saw it in 1961, almost certainly before [The] Open Square was published" (276). As reported in TimeLife’s True Crime: Mass Murderers, while staring at the Tower Whitman once remarked to a friend he met in the Marines, “A person could stand off an army from atop of it before they got to him” (46). Infamously, Whitman told UT staff psychiatrist Maurice Heatly during his first and only appointment four months before the shootings that he often thought “about going up to the top of the Tower with a deer rifle and shooting people” (TimeLife 56). According to Lavergne,

Heatly was nonplussed. He had heard many references to the Tower by students over the years. The Tower spawned many sick jokes such as “I feel like jumping off the old Tower!” To Heatly the Tower was a “mystic symbol” of the university and the frustrations of college life. Since its construction it had become impossible for many to think of UT without thinking specifically of the Tower. The doctor interpreted Charlie’s Tower reference as a “transient feeling” or an expression of depression common among students. Heatly concluded Charlie was not dangerous, but asked him to return at the same time one week later and/or to call at any time he needed help. Further treatment depended completely on Charlie’s initiative. Dr. Maurice Heatly would never see Charlie again. (71-72)

According to Lavergne, "By 1 August of 1966 many forces had contributed to decisions by Charlie Whitman to become one of the most violent and destructive individuals in American criminal history. Those forces were demons crusading to conquer his mind, and soon they would win, but many people face similar demons and they do not fight back by becoming violent" (75). Assuming Lavergne means "demons" figuratively, where did Whitman get the specific idea to imagine -- and use -- the Tower as a sniper perch?

In the national incredulity following the shootings, "attention fell on the unlikely person of Ford Clark of Ottumwa, Iowa, little-known author of a novel entited The Open Square" (275), Lavergne writes. Clark told Austin Statesman reporter Glen Castlebury two days after the shootings, "My first reaction was just 'oh, God, don't let it be due to my book.’ Actually, it kind of scared me. I was afraid he got hold of the book.” A United Press International story four days after the shootings reports that Clark "has received threatening phone calls since the rampage of University of Texas sniper Charles Whitman." Clark added, according to the unbylined report headlined "Tower Sniper Book Author Threatened," that "one caller from Dallas threatened to 'blow [Clark's] brains out with a plug from a shotgun.'" The UPI article, in one-sentence-per-paragraph wire service style, compares and contrasts additional plot points with Whitman's actions four days earlier. For example, "Like Whitman, the central figure of the novel took two jugs of water and 500 rounds of ammunition with him to the tower. In the book, the young man did not intend to kill anyone, but shot and killed two persons before his siege was ended." Wire service deadlines rarely accommodate close readings of novels, regardless of the pulp quality of the fiction. Nonetheless, in addition to leaving a great deal unattributed and making at least one error of fact (that Whitman moved from Florida to Dallas), United Press International or the editors at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette missed a number of significant potential correspondences between Charlie Whitman's life and the life of Ted Weekes, the reluctant sniper of The Open Square.

Given the similarities between not only certain specifics of the novel and Whitman's actions but also the backgrounds and values of the main characters and Whitman's own character, I can't help but wonder whether Charles Whitman was influenced by The Open Square regardless of whether he read it. Rhetorical theory is most helpful, at least in rhetoric's interpretive capacity, to get us through the places where the empirical evidence hasn’t yet been found. I could theorize why Whitman might have been influenced by a book he didn't certainly read -- by something we might call "the vernacular cloud" -- but I'd rather have facts if facts there be.

In When Books Went to War, Molly Guptill Manning lists the Armed Services Editions of classic and contemporary literature that were provided to soldiers during World War II. While the Armed Services Editions program was discontinued in 1947, anecdotal evidence indicates soldiers in Vietnam received boxes of paperbacks from publishers; perhaps paperbacks were circulated to and by Marines in the States as well. Perhaps before Whitman left the Marine Corps to return to Austin, Texas, he read a piece of marginal literature, a novel called The Open Square. Perhaps we'll never know for sure. For now, then, the question is in the realm not of certainties but of probabilities -- of that-which-can-be-otherwise. In other words, the question is perfect for rhetoric. While I find The Open Square odious and regret giving attention to it, to get at the question of rhetorical influence, to try to get from Point A to Point B, dwell upon it briefly we must.

The first page of the novel reports that a milkman has been shot near "the administration building of the local college" (5). The building's architecture is described a few pages later: "The administration building was two stories high -- a high two stories because the rooms inside had tall ceilings -- with a square tower on the roof almost as tall as the building and gold-painted dome on top of the tower" (8). At the University of Texas, the Tower has housed the campus and system administration from time to time over the decades. Further, "the Tower" by synecdoche represents the administration in conversation: "it depends what the Tower does," or "we’re waiting for the Tower to approve it." Both settings are also state capitals. In Austin, the Tower rises just fifteen blocks north of the dome of the Texas State Capitol; former UT President Homer P. Rainey, fired by the UT Regents for defending academic freedom, wrote a book called The Tower and The Dome: A Free University Versus Political Control. In The Open Square, on his way to climb the tower, the boy passes "pictures of past presidents of the university and past governors of the state" hanging on the walls (11).

Both in the novel and on the UT campus, the tower location -- the literal topos -- provides a strategically powerful vantage point. In the novel, the gunman, Ted Weekes, remarks from the tower, "You can see almost the whole town from here" (13). Further, both locations offer cover while retaining the ability to surveil: There are slits near the floor of the tower in the novel, and Whitman shot through waterspouts at the bottom of the observation deck of the Tower after experiencing return fire from below.

From the second page of the novel, the militarization of public space is obvious. Police Chief Ashton chooses a temporary office for his police command in a bank office with six windows that "faced the administration building and had venetian blinds. While Ashton's men could see out and across the large snow-covered lawn to the administration building, the boy there with the rifle could not see them and would not know they were there" (6). Comparative evaluations of gun power are also central to the logic of the novel from the beginning:

As Ashton walked between the double row of desks, a sergeant who was on the phone stopped him to say that the manager of the local sporting-goods store, whom he was speaking to, had several 30.06's which they were welcome to use; he would bring them over. Ashton nodded and went over to the desk Lieutenant Ross had set up shop on and looked at the map of colored pins that represented his men around the square and the placement of his four patrol cars. He was thinking about their artillery. In addition to the regular 16-gauge Remington pump guns which were carried in the patrol cars, the department had three .41-caliber carbines, old and slow but with a range of two miles and a lot of smash -- when they got there.

"I hope we get those sporting rifles soon. But until then," Ashton said, pointing twice, "carbines here." (6-7)

A few pages later, as Ebing, the night watchman who allowed the "boy with the rifle" into the administration building, describes the weapons the boy is carrying, the prose veers toward gunporn:

Ebing got his first good look at the work on the wood of the stock with its high, fine cheek rest. He noted the look of the action and the barrel; he heard the sound when the boy worked the bolt, and he knew the gun for sure -- it was one of those Weatherby Magnums like the ones in the gun catalogs. They didn't come any better. It was the gun you used to stop anything -- bear, moose and on up to and including elephant; a gun with all that velocity could knock a hole in a brick wall. Ebing lay there and watched the boy take a Lyman telescopic sight out of the small green felt bag and mount it on the rifle. The sight looked like one of those Wolverine 6-power jobs, only bigger. (12-13)

The boy had overpowered Ebing by pointing a rifle at his groin -- "the boy swung the rifle around in a small upward arc and sat there, with the gun pointed right at where Ebing wouldn't want to be shot, even though he wasn't a young man any more" (10) -- and taking his gun. From beginning to end, the novel clearly equates guns with masculinity -- the bigger, the better.

Throughout the novel, Ted Weekes, a student spurned by his fraternity brothers and his father for refusing to go along with what he saw as an injustice -- allowing the married son of a fraternity official to become a member of the frat without going through pledging and "hell week" -- is referred to as "the boy in the tower" or "the boy with the rifle in the tower." In addition to the weapons and gasoline, the supplies carried by Weekes are similar to what Whitman carried to the top of the UT Tower, having prepared to stay for a while: "The first suitcase held canned goods, a small GI kerosene cooker, four jugs of water and a roll of toilet paper” (12). The many similarities between what Weekes and Whitman carried led Austin coroner Dr. Coleman de Chenar to opine during a press conference after the autopsy was performed on Whitman’s already-embalmed body, “It is my personal feeling [Whitman] did read the book” (Petersen; cf. Akers, Akers, and Friedman 221-231).

The August 5 UPI story mentions yet another unattributed conjecture about reception of The Open Square: that it "enjoyed its greatest success on college campuses.” Yet this claim is not without potential warrants. In the absence of data about where the novel sold, the novel itself offers several warrants, including the college-aged antagonist, the college-town setting, and a scene from late in the book's chronological yet flashback-driven narrative:

To the right was the three-story chemistry building and North Hall, dotted with the flickering lights of student campfire. No classes today, with the danger of rifle fire with your algebra, but rather a holiday spirit. They even had their rooting section cat-calling at passing police cars and cheering for the boy in the tower who was, after all, one of their own. They probably had flasks. You could hear their occasional laughter, muffled by the falling snow.

We will return to the topos of algebra below. Meanwhile, the image of college students drinking and cheering a sniper in their midst -- but at a distance -- stands in stark contrast to scenes of contemporary shootings in educational settings. As semiautomatic assault rifles have replaced deer rifles, students run and huddle rather than celebrate -- and campuses offer strange mixtures of campus carry laws and active shooter training videos.

Yet The Open Square is not only about a student who goes to the top of a university tower to turn a university town into a war zone. The Open Square has another, arguably more central -- it certainly consumes more pages -- pulp passion plot. The obvious choices of character names contextualize both plots: "Weekes" is morally weak; "Ebing" is ebbing; Ashton is hot: in fact, he is often called "Ash" by Harry Keeler, the city manager whose internalized homophobia destroys his marriage when he finds himself attracted to the police chief: "He noticed that Ashton had, for his size, rather heavy thighs and calves and as he came around the desk he presented a mental picture that Keeler found somehow familiar and disturbing. Keeler knew he didn't have the slightest homosexual leanings -- certainly nothing like that. It was just that Ashton jarred him somehow, standing there beside the desk. Keeler actually felt light-headed for a moment" (21). After the police chief gives him two aspirin and a glass of water: "Keeler was feeling much better now; he felt almost gay.” On the back cover of the book it is revealed that Keeler "thought sex was dirty. And making love for sexual gratification certainly was a shameful way to treat a woman. Indeed, Harry Keeler was a fine person -- so calm and reasonable that he drove his beautiful wife nearly out of her mind and into the arms of the man she needed -- a tiger named Ashton," who also happens to be a war hero, having served in Korea and been awarded a Silver Star (36). Thus to the final character in The Open Square that we need to meet: Elaine, first Harry Keeler's wife and then Ashton's.

We meet Elaine soon after city officials begin coming to terms with "the boy with the rifle in the tower." Ashton "waited for her and she came up, wedging herself between the wall and the car.... [S]he did nothing more than touch Ashton on the arm, but that and the look of her was enough to remind him of how moist she was; for with him she had been a woman not dried and shriveled up, either between the legs, or above the neck, in the heart or in the mind" (23). Well, hello Elaine. Whatever your last name might be. A few pages later we learn about Elaine's values, remembering that this is a male author's representation of a female character's thoughts:

Harry knew what he was going to do. And because he knew he was going into city government and do things that would help, it gave him a purpose and a place, and because she was his girl it also gave her a place and a meaning. It was what she wanted out of life; to be a woman, a wife, a mother ... to a man. To give his life meaning because she was part of it. If that seemed too simple, that was unfortunate. It was the way she felt" (37-38).

Two paragraphs later, we learn this about Elaine, as her marriage to Harry begins to fall apart: "In the East he had kissed her often and put his arms around her, but at night she had wished for more fire from him; she wanted him to hurt her a little, to demand from her and not be so much like a child breastfeeding at the end of the day" (38). Finally, more than three-quarters of the way through the book, the pulp fiction passion plot culminates in Elaine getting the fire -- or at least the Ash -- she apparently wanted. Here lies the odious heart of this novel: its assent to what now is called rape culture. Not only is their rendezvous physically violent; the author remarks, "It was like being raped. Elaine was like the small bird watching the snake coil its way toward it, hypnotized by its own destruction” (138). And, finally, of course, “She joined in the rape now” (139).

Fawcett's marketing makes my case for the violent misogyny of the novel better than I could if I were to quote the whole book. Inside the book, printed on the flyleaf, dialectical companion to the back-cover revelation that Harry Keeler finds sex dirty, is featured part of the scene I quote above, enticing and invoking the kind of reader who would be interested in some violent soft porn and the vision of a frustrated male holding a college town hostage with "magnum" weapons.

Charles Whitman and The Whiteness of the Whale

It is the liaison of the "boy in the tower with a rifle" plot with the misogynist, homophobic, and violent pulp fiction plot that heightens the possibility, at least in my mind, of Whitman reading and identifying with -- and dissociating himself from -- specific characters in the novel. The unproblematic relation of violence and sexual passion in the novel, while revolting, is not atypical for the early 1960s in mass-market paperback fiction. And it remains typical of many cultural products today.

The two plots of Ford Clark’s Gold Medal novel combine two kinds of violence: domestic violence and rape culture in private space and seemingly random terror in public space, in the open square. Lavergne concludes his prologue to A Sniper in the Tower with these observations:

It took Charles Whitman an hour and a half to turn the symbol of a premier university into a monument to madness and terror. With deadly efficiency he introduced America to public mass murder, and in the process forever changed our notions of safety in open spaces. Arguably, he introduced America to domestic terrorism but it was terrorism without a cause. (xi)

Note the double-voicedness of the word "cause": First, there were a multitude of antecedent causes that prompted Whitman to act as he did. Then, people ascribed causes -- a posteriori purposes -- to his actions, emplotting the personage of Charles Whitman and his deeds in narratives intended to delight or disturb, celebrate or caution.

Charles Whitman was a former Marine sharpshooter who had been -- as told by Lavergne and by psychologist Stuart Brown, not to mention by Whitman himself via his journals in the Austin History Center -- regularly beaten by his father, surrounded by guns, denied any chance to learn how to play while becoming the nation's then-youngest Eagle Scout, and witness to the daily brutalization of his mother by his father. In his journals, Charles -- Charlie -- Whitman admitted to assaulting his wife, just as his father, Charles A. Whitman, had assaulted his mother before him. The elder Whitman, quoted in TimeLife’s True Crime: Mass Murderers, remarked after the shootings, "I did on many occasions beat my wife, but I loved her and love her to this day…. I have to admit it, because of my temper, I knocked her around" (40). Lavergne adds, "When discussing relationships, C.A. Whitman had a propensity for mixing love and violence” (3) -- a propensity, as evidenced by the note that Charlie Whitman left next to his mother’s body, shared by his eldest son:

I have just taken my mother’s life. I am very upset over having done it. However I feel that if there is a heaven, she is definitely there now, and if there is no life after, I have relieved her of her suffering here on earth.

The intense hatred I feel for my father is beyond description. My mother gave that man the 25 best years of her life and because she finally took enough of his beatings, humiliation, degradation, and tribulations that I am sure no one but she and he will ever know -- to leave him. He has chosen to treat her like a slut that you would bed down with, accept her favors and then throw a pittance in return. I am truly sorry that this is the only way I could see to relieve her suffering but I think it was best. Let there be no doubt in your mind that I loved the woman with all my heart. If there exists a God, let him understand my actions and judge me accordingly. (53)

In the summer of 1966, Charles Whitman was nearly out of money and used dextroamphetamine and tranquilizers to attempt to manage his moods. Because of his father’s violence, his mother had left his father a few weeks earlier. Subsequently, Charlie drove to Florida to move his mother to Austin, and his father hounded them with phone calls (TimeLife 49).

In addition to Whitman’s family stress and substance abuse, historian Doug Rassinow, in his book The Politics of Authenticity, argued persuasively that Charles Whitman was also a racist, inflamed by white supremacists, who chose his victims not randomly but for specific reasons. Rassinow describes Whitman as “a student with strongly racist views and apparently with ties to the Minutemen” (175). TimeLife’s True Crime: Mass Murderers quotes anecdotes reported by Whitman’s friends of his bullying African American students and international students.

Finally, although Whitman’s body was for unknown reasons embalmed before an autopsy was conducted, Dr. Coleman de Chenar discovered a “pecan-sized” tumor at the base of Whitman’s brain. Both de Chenar and the subsequent Connolly Commission investigation of the shootings were inconclusive about the causal connection between the tumor and the first public mass murder in US history. Among the many people who have contacted me unsolicited over two decades about Charles Whitman are one of his cousins, asking me whether it was safe for her to have children -- a question clearly beyond my expertise -- and Whitman’s best friend from the Marines, who is still wrestling, more than a half century later, with the fact that Whitman told him that the Tower would be an unparalleled sniper perch. He is working on a book, he says, called “The Charlie I Knew.”

Causes may forever remain unknowable -- even unto those who perpetrate violence, as Whitman's final letter suggests: "I don't quite understand what it is that compels me to write this letter. Perhaps it is to leave some vague reason for the actions I have recently performed. I don't really understand myself these days" (TimeLife 52). In the fifty years since the shootings, conjectures about what caused Charles Whitman to do what he did on August 1, 1966, have often revealed as much about the person making the claim as about Whitman. In that way, Charles Whitman has for the past half century served a purpose similar to the great white whale in Melville’s Moby-Dick: the unfathomable creature onto which we project our imagined yet otherwise inarticulatable terrors. “The whale is many things to many people,” remark Hubert Dreyfus and Sean Dorrance Kelly in their 2011 book All Things Shining: “The whale is a mystery, so full of meaning that it verges on meaninglessness, so replete with interpretations that in the end they all seem to cancel out” (169).

The Rhetorical Influence of Rage

One other comment from coroner de Chenar, reported in the TimeLife True Crime: Mass Murderers volume, provides another possible way out of this labyrinth -- or fun-house? or prison-house? -- of conjectures and claims about causes and consequences. De Chenar said at the press conference announcing the findings of the autopsy that Whitman was “a walking charge of dynamite waiting for a spark.” While it is possible we will never know whether The Open Square provided the inventional spark that led Whitman to imagine the Tower as a sniper perch, the fuel-fire metaphor prompts recollection of Wayne C. Booth’s reluctant conclusion in The Company We Keep: An Ethics of Fiction that “if books can be good for you, they can be bad for you, too.”

Indeed, author Stephen King, who has made nearly half a billion dollars writing and selling books, recounts in his essay Guns that he demanded his publisher pull one of his books from the shelves -- the pseudonymous novel Rage, published under the name Richard Bachman -- after it was found in the backpacks of two boys who shot and killed teachers and fellow students at their public schools. One boy committed the murders in his algebra class and then quoted from the novel -- “This sure beats algebra, doesn’t it?” -- before another teacher knocked the gun away. King subsequently learned of two additional fatal school shootings in which boys who brought guns to their schools and terrorized fellow students and teachers said they got the idea from reading Rage. “That was enough for me,” King wrote. He continued,

According to The Copycat Effect, written by Loren Coleman, I also apologized for writing Rage. No, sir, no ma’am, I never did and I never would. It took more than one slim novel to cause [the four boys] to do what they did. These were unhappy boys with deep psychological problems, boys who were bullied at school and bruised at home by parental neglect or outright abuse…. All four had easy access to guns…. My book did not break [the four boys] or turn them into killers: they found something in my book that spoke to them because they were already broken. Yet I did see Rage as a possible accelerant, which is why I pulled it from sale. You don’t leave a can of gasoline where a boy with firebug tendencies can lay hands on it.

If you do not find the physics or metaphysics of the fuel-fire metaphor satisfactory -- or if you do not deem Stephen King an adequate arbiter of the broken and the whole -- consider an agricultural turn: On the evening of June 17, 2015, when the twelve faithful at Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, welcomed the young white man into their fellowship, the verse under discussion offered an account of rhetorical influence that remains haunting nearly two years later. As reported in the New York Times three days after the shootings that left nine dead, “It was unusual for a stranger, much less a white one, to come to the Wednesday night session, but Bible study was open to all, and [Rev.] Pinckney welcomed him. They sat together around a green table, prayed, sang and then opened to the Gospel of Mark, 4:16-20, which likens the word of God to a seed that must fall on good soil to bear fruit” (Fausset, Eligon, Horowitz, and Robles).

Meanwhile, King’s Rage continues to circulate, and King has published two apologias for writing the novel, the first in 1985, before the book was found in the lockers or backpacks of school shooters, before school shootings became almost routine in the United States, before gun violence became epidemic, and before police forces became thoroughly militarized. In “Why I Was Richard Bachman,” King’s introduction to the 1985 “omnibus” edition of Rage and three other novels King published under Bachman’s name, King offers copious reasons intended to defend his decision not only to publish under another name but to construct an identity around this Richard Bachman, this alter-ego, to distance King’s work from Bachman’s as far as possible. These reasons range from -- in King’s words -- “Sometimes something just says Do this or Don’t do that” (v) to “The numbers have gotten very big. That’s part of it. (OVER 40 MILLION KING BOOKS IN PRINT!!!, as my publisher likes to trumpet)…. [S]ometimes I feel like Mickey Mouse in Fantasia. I know enough to get the brooms started, but once they start to march, things are never the same)” (vi) to “I think I did it to turn down the heat a little bit; to do something as someone other than Stephen King…. Sometimes it was fun to be Bachman” (vii). Most remarkable about his first apologia for Rage is that King ended three of the introduction’s 14 short sections this way: “Good thing I didn’t murder anyone, isn’ it?” (v); “Good thing I didn’t kill anybody, huh?” (v); and “I repeat, good thing I didn’t kill someone, huh?” (vii).

Here the ratios of rhetorical influence come very possibly full circle: King started the novel -- originally called “Getting It On” -- in late 1966, a few months after the Tower shootings. King has, by the way, described Charles Whitman as “America’s favorite sniper,” but that was well before our most recent undeclared wars and the ascendancy of the iconoclastic American Sniper. In any case, in his second introduction to the Bachman books, published in 1996, King reconsiders his responsibility and implores, “All I can say … is that if there is anyone out there reading this who feels an urge to pick up a gun and emulate Charlie Decker, don’t be an asshole. Pick up a pen, instead…. Violence is like poison ivy -- the more you scratch it, the more it spreads” (“The Importance of Being Bachman” vi).

“That Letter Killed Marc”: The Rhetorical Influence of Guns

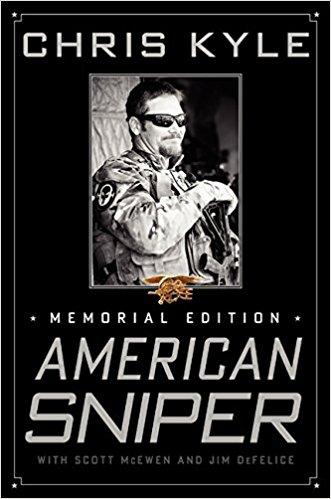

This chapter has offered you implicitly and explicitly several different ways of thinking about rhetorical influence. The two editions of Chris Kyle’s #1 New York Times bestselling memoir American Sniper, originally published in 2012, and the Clint Eastwood film of the same name, released in 2014, provide a few more. The memoir and the film tell largely the same story:

From 1999 to 2009, U.S. Navy SEAL Chris Kyle recorded the most career sniper kills in United States military history. His fellow U.S. soldiers, whom he protected with deadly precision from rooftops and stealth positions during the Iraq War, called him “The Legend”; meanwhile, the enemy feared him so much they named him al-Shaitan (“the devil”) and placed a bounty on his head. (Harper Collins)

Though Kyle writes honestly about the pain of war, including the deaths of two close SEAL teammates, both the memoir and the film were criticized for contributing to Islamophobia. Further, Kyle states repeatedly that he “likes” or “loves” war, suggesting how technological advancements have thoroughly dehumanized an already inhumane practice.

Despite his vocation for killing, witnessing the deaths of his buddies, particularly of fellow SEAL Marc Lee, left Kyle with posttraumatic stress disorder, a condition he recovered from in part by helping disabled veterans, providing them with exercise equipment and personal training, even taking some to shooting ranges. It was on a shooting range that Kyle and a friend were shot and killed by a 25-year-old US Marine Corps veteran, also with PTSD and diagnosed schizophrenia.

Kyle was murdered as Eastwood was finishing the film version of American Sniper. Kyle was already known as “The Legend” by his fellow troops, but Kyle’s death enabled Eastwood and former Goldman Sachs banker Stephen Mnuchin, who financed the film -- and who is now treasury secretary -- to create the myth of Chris Kyle, American Sniper and fallen hero. Among the several differences between Kyle’s memoir and Eastwood’s film, one factual difference stands out in the context of accounts of rhetorical influence, and it involves the death of Kyle’s SEAL brother, Marc Lee, in Ramadi in 2006.

In Ramadi, Lee drew fire when he exposed his position to try to redirect attention from his fellow soldiers. Kyle tells the story that way, as does the military’s official account of Lee’s death. Lee was posthumously awarded the Silver Star, the Bronze Star with Valor, and the Purple Heart. Lee majored in Bible & theology in college before changing his major to law, and was by all accounts a sensitive as well as brave soldier. Lee wrote a letter home shortly before he died (“Marc’s Last Letter Home”) -- also called, by some, his glory letter. Here is an excerpt:

Glory is something that some men chase and others find themselves stumbling upon, not expecting it to find them. Either way it is a noble gesture that one finds bestowed upon them. My question is when does glory fade away and become a wrongful crusade, or an unjustified means … which consumes one completely?

Yet Eastwood cannot let Marc Lee’s mix of valor and compassion -- of complex human dignity and struggle -- stand. In the film version of Kyle’s story, Kyle, played by Bradley Cooper, tells his wife, Taya, played by Sienna Miller, “That letter killed Marc.” Nothing remotely like that is in the memoir.

We rhetoricians are taught to read for the unstated premises, for the part of the enthymeme that is missing. What is missing here and left for the viewer to supply is not merely the suggestion that the act of composing would somehow lead to death -- all of the sudden I prefer Stephen King’s account, that writing can stave away various kinds of madness. What Eastwood -- and, it must be said, Cooper -- intend audiences to take away from the film version of American Sniper is that anything short of loving war and never questioning the rightness of the fight or the evil of the enemy -- any questioning of the single narrative -- will be fatal.

In the wake of The University of Texas at Austin’s thirty years of repression about the victims of the Tower shootings, Charles Whitman became a cultural antihero, celebrated in film, song, and “fan club” websites. In a recent article, “What’s so American About John Milton’s Lucifer?”, in The Atlantic, Edward Simon argues that “Milton’s Lucifer can be read as a kind of modern, American antihero, invented before such a concept really existed. Many of the values the archangel advocates in Paradise Lost are regarded as quintessentially American in the cultural imagination…. What Milton’s Paradise Lost, the first version of which was published in 1667, also demonstrates is what can be so dangerous about mistaking an antihero for a hero.”

The question of rhetorical influence continues to hector scholars of rhetoric from across the proximate but not often enough allied disciplines of communication and writing studies. In the absence of empirical evidence of effect, texts are nonetheless often said to "invite" responses from real or imagined listeners, readers, viewers, audiences, publics. Partly in response to the problematics of rhetorical influence, scholars gathered in late February 2012 at Texas A&M University to discuss the concept of "symbolic violence." Did, for instance, potentially violent rhetoric in the form of posters with crosshair targets over specific congressional districts contribute to the shooting that resulted in severe brain injuries to then-US Representative Gabrielle Giffords and the public murders of six people at a political rally in Tucson, Arizona, in January 2011?

Fatal public gun violence has become so common in the second decade of the twenty-first century that questions of inventional causality -- rhetorical influence -- demand scholarly interrogation sufficiently comprehensible to inform public deliberation. Interdisciplinary rhetoricians should continue to work to find or create persuasive, probabilistic accounts of whether certain kinds of rhetoric might incite certain kinds of violent consequences. Furthermore, we must do so without ignoring the roles of all forms of political, economic, and communicative oppression. For these purposes, close examination of texts is necessary but not sufficient.

Not only language affects language. And language -- and the absence of language -- affects and effects more than language alone.

3. I want to thank the graduate students in my Spring 2017 Rhetorics and Poetics seminar for a particularly great discussion of Milton’s Areopagitica. We read Areopagitica along with Of Education and excerpts from Paradise Lost. Alongside the seventeenth-century Milton we read Nicholson Baker’s novel Vox and Stephen King’s pseudonymous novel Rage, originally called “Getting It On” -- more on that novel later in this chapter. I wrote in Citizen Critics in part about readers who wondered whether James Joyce’s facility for writing about psychopathology meant he was a psychopath. The early twenty-first century provides another fitting context for pausing to ask and reflect together upon the possible consequences of making Lucifer so damned attractive.