In 2013, I lost my grandmother and my best friend. This is my way of remembering them. This is a story about working with their loss.

In their digital book Techne: Queer Meditations on Writing the Self, Jacqueline Rhodes and Jonathan Alexander theorize ways “to provoke visceral awareness of the interimbrication of bodies and technologies, orienting and reorienting one another” (“Introduction”). My multimodal memoir attempts such provocation in regard to experiencing the death of my loved ones. I situate my own experiences of remembering to not just provoke, but to also evoke the act of memorializing as an act of healing. This memoir, then, provides me the opportunity to theorize backwards in an attempt to heal the wounds of loss that have forever shaped my ability to write and produce scholarship.

All the pictures and videos in this memoir are mine. I have collected them together as my first act of memorializing because usually the only thing we can do after loss is remember.

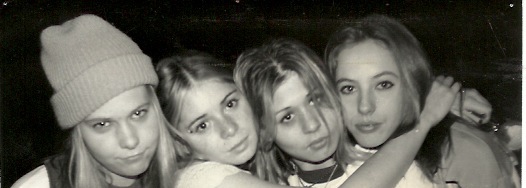

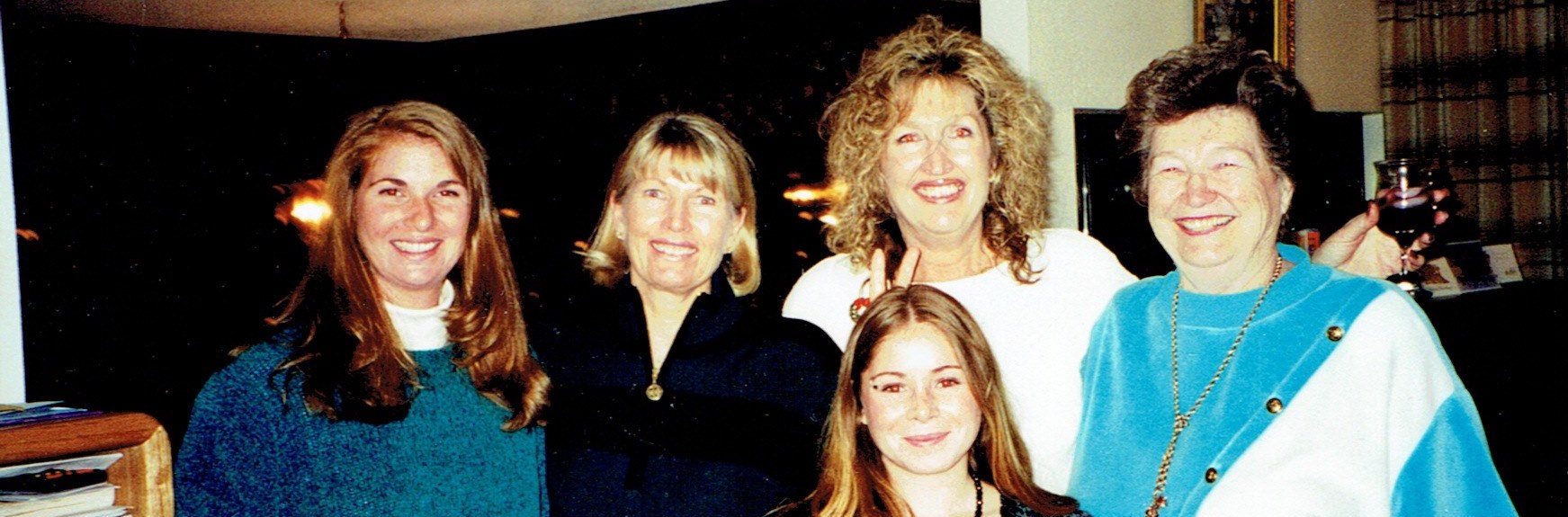

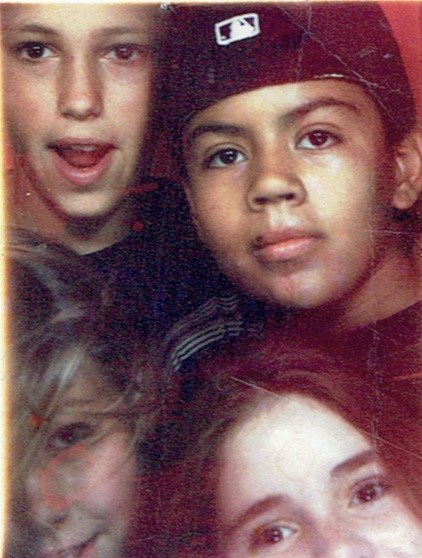

From left to right: Sari, Les, Candace, Chantel. The four best friends.

Me and my grandmother.

A note on moving through this text: You will scroll through waves of theory, reflection, memory, prose, image, and eventually video. The purpose of this is to imitate the messy act of remembering and the fragmented way we come to reposition the past in the present. Every underlined phrase or word has an accompaning hyperlink. You may, at times, feel lost between times, as we sometimes are. This is the sort of embodied provocation I adopt from Rhodes and Alexander. My hope is you engage with the text in a sort of playful way, but one that asks you to use your body as part of the experience.

Joshua trees seen through a desert rain-smudged windowpane.

I begin theorizing my memoir on loss with how Rhodes and Alexander use Sara Ahmed’s theory of orientation from her book Queer Phenomenology, in which she argues,

Orientations are tactile and they involve more than one skin surface: we, in approaching this or that table, are also approached by the table, which touches us when we touch it. As Husserl shows us, the table might be cold and smooth and the quality of its surface can only be felt once I have ceased to stand apart from it. This body with this table is a different body than it would be without it. And, the table is a different table when it is with me than it would be without me. Neither the object nor the body have integrity in the sense of being “the same thing” with and without others. Bodies as well as objects take shape through being orientated toward each other, as an orientation that may be experienced as the co-habitation or sharing of space. (54)

This phenomenological frame allows Rhodes and Alexander to embody narrative as they determine the ways in which they are oriented to—and through—technologies. For the purpose of this memoir, I lean on my memories captured in images, prose, and video to analyze the ways in which these texts (re)make memory into my story about loss.

As Anne Frances Wysocki reminds in "Seriously Visible," "It is old and not uncriticized news that" hypertextual documents encourage readers to be more engaged with the text they are reading and offer visual elements to their textual argument that demand serious attention (37). My use of this medium, with its hypertextual and multimodal affordances, allows me a way to engage with the various forms of texts I have collected here to create a visually complex memoir about loss—one I can embody over and over again as I come back to this essay and recompose the narrative. New pieces of this story about loss emerge through time's unfolding in my life, bringing with them narrative digressions, departures, and affirmations.

For every moment of composing, I enact the embodiment of this narrative and bring to view a story yet written from my mind. Joddy Murray asserts that "the impact of images, language, and emotion becomes immediately apparent to any theory of consciousness. All three work to create an environment in which text generation and imagination engage the mind and its consciousness to produce text—to write" (124). So it is that I take from Murray his understanding of the role consciousness plays in composing and connect it to the phenomenological frame Rhodes, Alexander, and Ahmed give me.

"Working with Loss," first and foremost, becomes a space in which I bring my experience with loss into being through a hypertextual, multimodal writing process. Composing this memoir has enabled me to make sense of the year when my grandmother's and Sari's death nearly incapacitated me. I stopped writing entirely for months, feeling that my voice had vanished along with them. It took time and a lot of stumbling to begin writing again.

This memoir is the first full-length anything I have been able to write without grief taking hold, which is not something easy to proclaim because writing is the primary function of our work in rhetoric and composition.

It was by writing about loss that I was able to work again. The act of memorializing allows my voice not to be silenced by overwhelming grief, but to embody that grief, give it a name, honor it, and work with it. This is my story about loss.

A dandelion plucked from my yard. 2012.

Remembering Shirley

I come from a long line of strong women. My grandmother was the strongest.

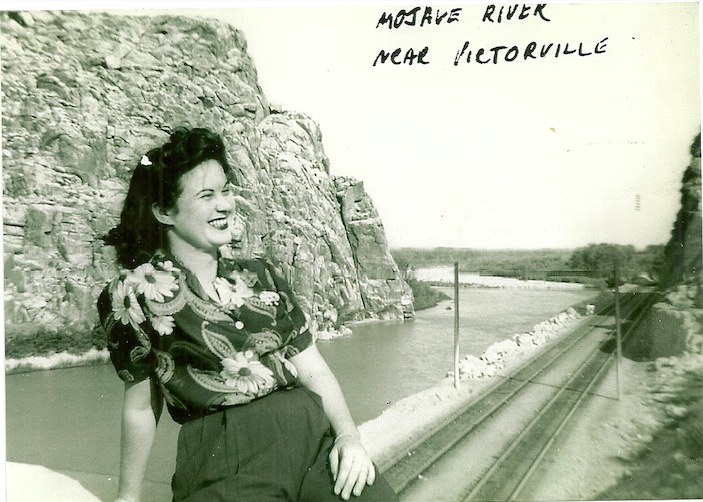

A young, vibrant Shirley Hutchinson smiling over the railroad tracks in Victorville, CA. Picture taken by my grandfather. Scanned and emailed by my father.

Me and my grandmother in her backyard. 1984.

Photographed by my father.

TMy grandmother, childhood friend Gayelyn, and me on my fourth birthday. Photographed by my father.

Scene: Winter 2012.

It's snowing.

My grandmother becomes ill.

I have been estranged from my family since the summer before.

Familial differences.

Political differences.

Race differences.

Class differences.

In an accidental admission, my brother tells me that they've hospitalized her.

Despite all her wishes, my family put her in a nursing home.

Despite her wishes.

In spite of her dementia.

|

|

|

| Snow the night before February 7th. |

Selfie, day of. | Holding hands. |

February 7th, 2012

I sneak into the nursing home where they've hidden my grandmother. I am dressed to the nines: heels, a dress, my "nice" cardigan, a crystal broach. I approach the desk. No one is there. I keep walking down the hall. Corridor after corridor, I look into each room. For her. Her smiling face. Eventually, I find her.

She looks distressed and uncomfortable. I reach out and grasp her hand. I snap a picture of them together, one withered by time, the other from early onset arthritis from writing too much.

*snap*

None of that matters now. We're together. The only problem? She doesn't know who I am. She will hold no record that I am here.

"I suppose that's for the good," I think, "This way, they'll never know I snuck in to see her."

My grandmother was the only person in my family to support my decision to go back to college after having my son. I suppose her support had a lot to do with her regret at not attending herself. After listening to my latest report from school while the two of us sat on her couch, she’d recount the stories of her English teacher’s mentorship and how that mentorship landed her a job working for an attorney in Texas, and then how that Texan attorney introduced her to my grandfather. The story would run off, just as she did with him, to California, where she had my aunts and my father—events leading up to him having me. Every tangent she would bring back to my education, ending her story with declarations of pride for my achievements and a cause to celebrate with a glass of Crown Royal on the rocks. I’d squeeze her hand as the ice clinked in her glass, watching tears well up in her eyes, crystallizing. She was my rock. She was what was inside me that makes me so driven and resilient.

| My archive. Taken by my mother. < |

My archive. Taken by my mother. |

My archive. My mother and cousin looking on. |

I was tasked to compose this memoir in an assignment for Alex Hidalgo's class Academic Memoirs Across Media. The first thing I did was run to my photo albums and gather together every photo I have of my grandmother. Shirley lived an extraordinary life. From building government bridges after WWII with a construction company she shared with the grandfather I never met to managing a casino in the middle of the desert, my grandmother set a standard for the working single mother in my mind.

I had no pictures of the Shirley who lived before I was born. In fact, I have very few pictures of her at all. Delving into my own archives, the two boxes of photographs I've carried with me across the country, I realized these are all the captured memories of her I own. And I don't even remember all of these moments.

So I turned to my family, thousands of miles away.

"Do you have pictures of Grandma you can send me?" I ask my father. I ask my aunt. They're coming, they say. My aunt's never arrive. My dad emails a few of the old ones here. And in their arrival to my email inbox, I start to recall pieces of her I barely knew.

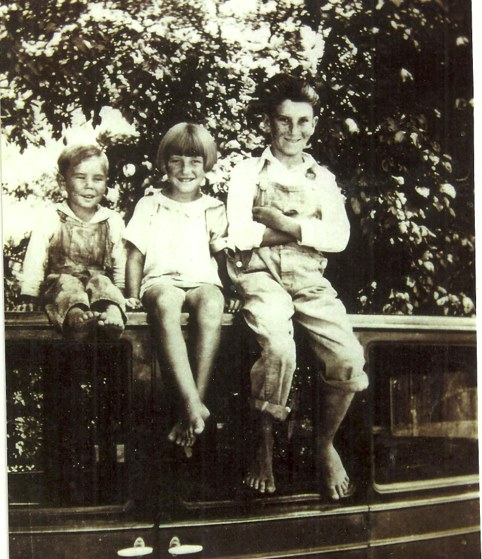

Uncle Wayne, Shirley, and Uncle Don. Emailed to me by my father. Circa late 1920s.

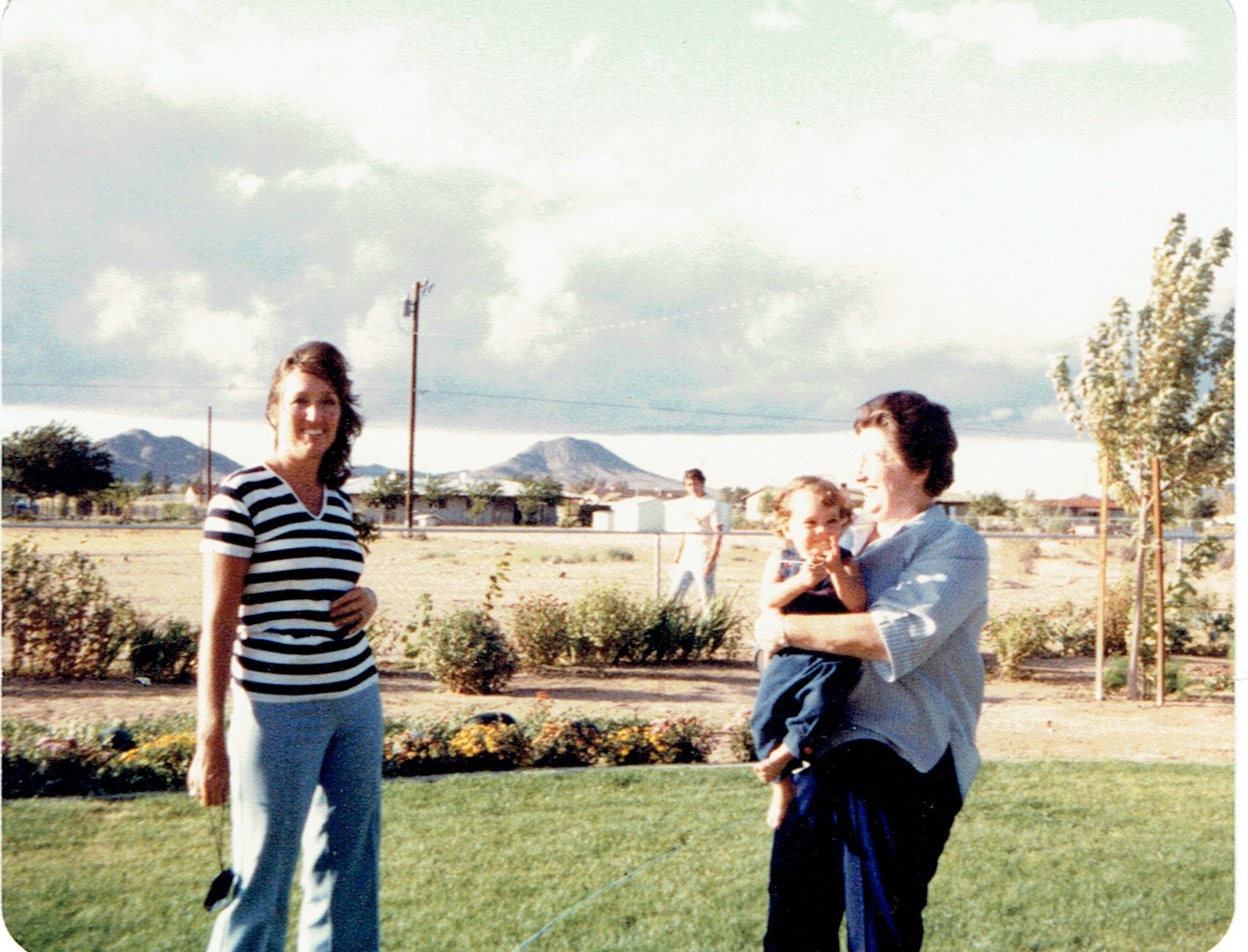

My Aunt Leigh, me, and my grandmother. Bell Mountain is in the background, along with my cousin. Photographed by my father. 1982.

Shirley grew up in Texas during the Depression. She never spoke to me about surviving then, through the specific hardships I've come to know from lore and history classes. Instead, I got one storied bit from her. To make it through the especially rough financial times, they used to make strawberry wine and sell it to folks driving through town. Serving alcohol would be a running theme throughout her life.

Life of the party.

***

My grandmother used to say that she loved the desert because of her ability to see it stretch out into the horizon. She would stare out her kitchen window, through her yard, past Bell Mountain, and toward the end of the sunset. She would have this wistful look on her face, eyes still (and always) twinkling. She would hold my hand, turn to me smiling, and walk on. The ice in her glass of Crown Royal continually clinking.

Write the map to where you live. Start as close or as far from your home as you wish. The map back to home reads like a Joshua Tree. Start from any point, all you see are light green fronds. They pierce your skin if you dare to touch too close. I suggest holding yourself together tight. The fronds will shred into a million little threads if you pull a single one too hard. So don’t. Press lightly. Be prepared to move on. When you follow them down, you’ll find the buds of the tree’s flowers. They’re rare, so be gentle. Look, but keep going. At the bottom of the fronds and the flowers are the branches. They’re covered in this burly, bristly fur like thick, unmattable hair. You can’t braid it or put each strand together. They’re there to make sure you take your time. That you keep looking closely. That you don’t get too close. That you don’t stay long. As you follow the branch you’re on down, you’ll notice how many other branches there are around you, how many others can be traveling on this road home.

“No matter how badly we want to leave, we always come back.”

So says our lore, we the people who live with the Joshua Tree.

You’re walking your branch, hoping you might catch a glimpse of who, too, gets to come home—who else has stories with them about why they left. You’ll meet where the branches and trunk meet. Their union is symbolic of years of growth. So is yours.

The trunk has shed the Joshua Tree’s fur over its lifetime of weather and experience. Its skin feels gnarled to the soft touch of your fingertips. The map will tell you to place your palm against it to feel the desert pulse of yesterdays. You will, because you will need to go on. You’re not home until you plant your feet on the ground.Dust will gather in your toes, even if you’re wearing shoes. It’s the nature of this desert’s sand. Like air, the tiny bits of dust cling to you. They’re your mark of travel.

They’re your mark you’ve arrived.

Signify the moment by standing in the shadow of the tree. Tell us the story of how you’ve come home. We’re close behind, learning.

Clockwise from left: Cousin Ryanne, Aunt Lynne, Aunt Leigh, Shirley, and me. My father's house. Christmas 1998.

.jpeg)

Shirley, me, my ex-stepmother, and my father. Hawaii, 1999.

In "Traces of the Familiar: Family Archives as Primary Source Material," Wendy B. Sharer writes about how, after losing her grandmother during the first year of her PhD, she had a desire to explore her grandmother's history in deeper detail. Sharer's grandmother had taken part in post-suffrage political activism. Sharer recalls her feeling remorse at having not had more time to speak with her and learn about her life (48).

Sharer and I have a lot in common. I, too, lost my grandmother early--in the year between my MA and PhD. I, too, wish I had more time to learn about my grandmother's incredible and inspiring life. All we both have left are traces of lives led by incredible women. Sharer speaks of her scholarly obligation to tell her grandmother's story, an obligation I understand and am honoring myself, here.

Sharer explains that "writing history is not merely an exercise in the objective recording of factual information. Rather, it entails the careful selection and arrangement of historical traces from among an infinite number of possibilities" (53). Unfortunately, my grandmother's story, at least as I can tell it, is limited by the sparseness of my archive.

My father with his mother. Benihanas in Las Vegas. 1993.

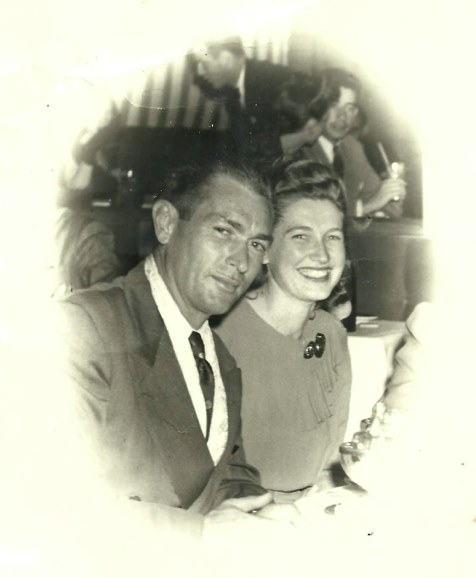

Lloyd Sterling and Shirley Hutchinson at Ciro's in Hollywood. 1946.

I have had the enormous pleasure of learning more about my grandmother by simply mentioning the making of this memoir to family, giving my Aunt Leigh, my father, and even my mother opportunities to remember her life for me.

My dad would tell me, everyone thought my grandfather looked like Errol Flynn, so of course he became Flynn's stunt double in Hollywood. Recalling the likeness between my grandfather and Flynn would tickle my grandma.

On the phone a couple days later, my Aunt Leigh recounted my grandmother's timeline from leaving Texas to opening and running a saloon on the side of a desolate, two-lane highway in the high desert of California. Men used to ride their horses up to the bar for drinks; my grandmother and great-grandmother would greet them with jokes.

My grandmother, like everyone on both sides of my family, had a fondness for horses.

My mother's act of remembering my grandmother on the phone with me is a little more complicated and triggering then the acts made by her children.

As a Mexican and an outsider, my mother remembers fighting for acceptance from her ex-mother-in-law. Memories surface of racism and classism. My great grandmother's insistence that the Hutchinson family's German blood remain free from spoil. My grandmother's deep love and respect for my mother despite this fact, despite the brownness of my mother's skin. But how, when my dad left her, my grandmother told my mother that Hutchinsons keep to themselves. Divorce was to cut her off, nearly irrevocably forever, from the family she had married into.

Until, that is, my grandmother would be on her deathbed, needing the care of the nurse her ex-daughter-in-law would always be.

Scene: March 2012.

They've brought my grandmother home from the nursing home.

Her hip has healed from her fall.

My Aunt Leigh decides she cannot care for her ailing, dementia- bound mother.

She asks my mom, the trained nurse, to come help care for her. That they'll pay her.

The Hutchinsons have no problem letting in "the help" so long as its on their terms.

My mother agrees.

She was never one for grudges.

She'll tell me, "I've always loved your grandmother, you know."

I'll nod, jealous she can spend time with her when I can't, but also feel relieved my mother is there.

And at my grandmother's bedside my mother will stay, listening to her exciting stories over and over.

And over.

Patiently. Happily. Proudly.

"Your grandmother was a remarkable woman."

I'll nod to the woman who never went back to her maiden name.

We're all Hutchinsons.

Having rekindled my relationship with my father and his side of my family the Christmas of 2012, I was finally allowed to spend time with my grandmother. A few months later, in June, I graduated with my master's degree.

My aunt had asked me to look for a bedpan at the local pharmacies on Fourth of July weekend. Those that were open had none in stock. The hospitals couldn't be bothered.

My son and I drove around the desert in that stark heat, looking.

Days later, on July 10th, my grandmother died, slowly succumbing to dehydration.

I remember seeing the light, yellow polyester shirt clinging to her sagging skin, barely covering her thin withered body. My son and I took turns holding her hands.

We both got to say goodbye.

It is there, in that particular corner of her backyard (see previous image) where I sat crying while my family gathered inside, drinking wine. They would congratulate my cousin Ryanne for marrying well. I would be lectured by my aunts on wasting my time in college when I could be finding a husband. This infuriated me, and I left, peeling out of my grandmother's driveway, hitting a wooden fence. My Aunt Leigh called the next day asking me to pay to have it fixed.

Less than a month later, I moved to rural Kansas, taking a full-time temporary job as faculty at a university there.

I have yet to return to my grandmother's house, but I hear my Aunt Leigh took out this patch of grass and filled it with rocks.

To save water.

In Kathleen Wider’s “In a Treeless Landscape: A Research Narrative,” Wider approaches the problems with trying to encapsulate a life into biography.

She proposes, “Making sense of a person’s life is always a work in progress, since each life is embedded within the complex web of connections that constitute reality” (71). Like Wider, I do not seek to compose a cohesive story about my grandmother, or Sari, or even my experience with losing both of them. Instead, I seek to make this a digital space forever open to composing a story about remembering them.

Wider continues,

“Since it is impossible for humans to attain [complete] understanding [of any one life], we must settle for a partial and ongoing modification of our understanding” (71).

I choose this ongoing modification of our understanding. That’s the beauty of digital composing processes—they can remain forever open. And because of that, I am free to reflect here and now on their lives as I remember them, with the hope that more memories will come the more time I spend composing this memoir.

Remembering Sari

A couple months later, while I was working at the university in Kansas, my best friend Chantel called me to tell me that our other best friend, Sari, had died unexpectedly the night before in her bed from an asthma attack.

Faces of Sari through the years.

Scene: A Tuesday night in early February, 1997.

Two teenage girls are sitting in an old Hyundai Accent in the empty parking lot of a country club; it's been raining.

The asphalt looks like black glass.

Obsidian.

They giggle about boys, gossip, high school.

Sari takes her index finger and draws their names in the condensation on the windows.

"Sari. Plus. Leslie. Equals. Best Friends. Forever."

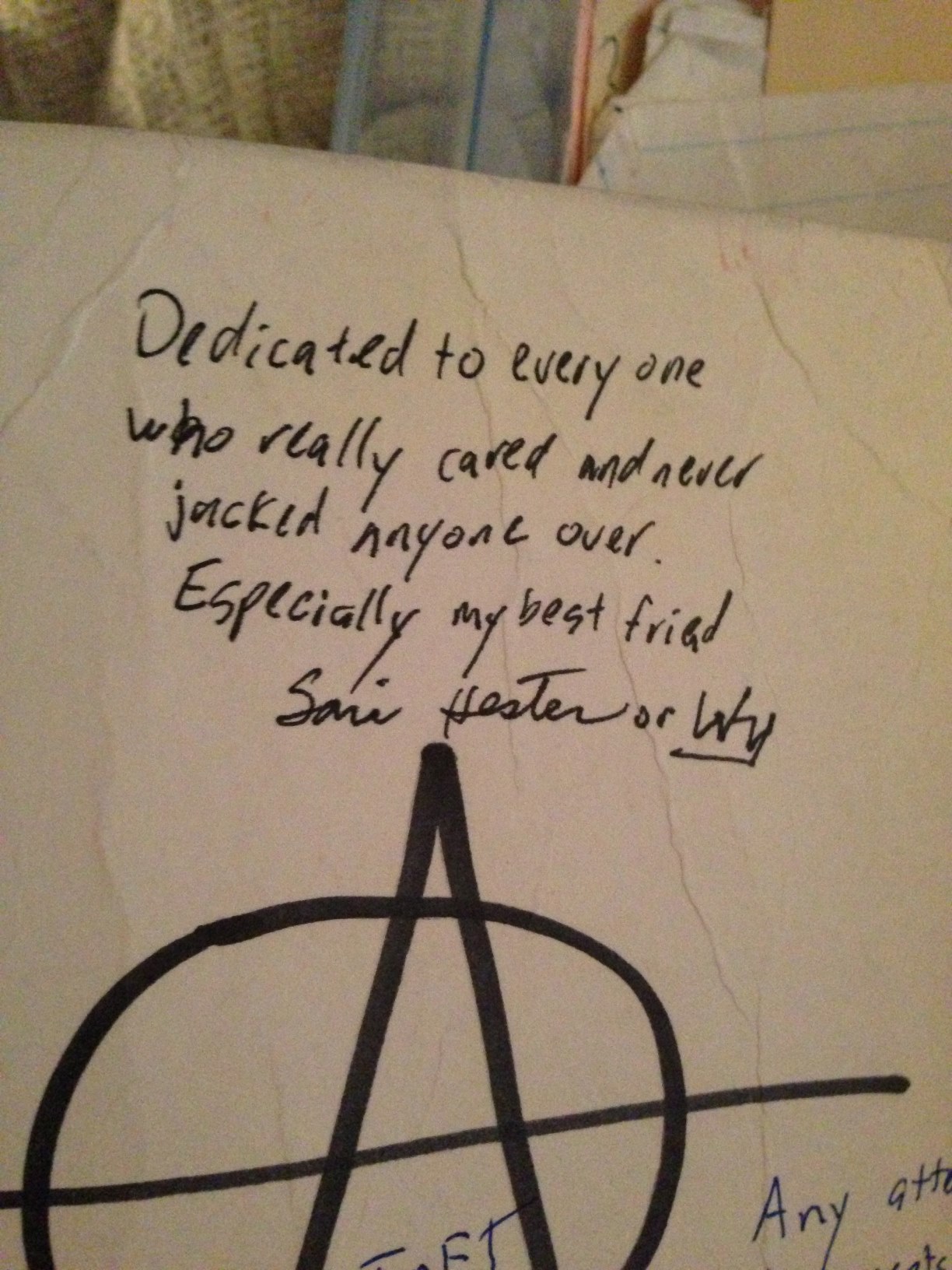

Journal inscription. Circa 1994.

Claude Mark Hurlbert and Michael Blitz discuss the role writing plays in healing after loss and death. Their essay from Composition Studies, "Equaling Sorrow (A Meditation on Composition, Death, and Life), found me a few short months after losing Sari and my grandmother. I felt drawn to the way they theorized writing, and in an homage to those feelings along with the spirit of remembering, I am integrating them here.

Hurlbert and Blitz believe that

Writing is not simply a way to learn—and know—about one’s own life and death. Writing brings us as close as we can be to the things we write about, even when those things, and people, have passed away and into memory and, often sorrow. Writing puts us—and keeps us—in the thick of living because it is an act of living (85).

The focus on keeping in the thick of living makes the act of memorializing a phenomenological relationship with life through the embodied experience of writing. By writing, we are embodying an act of living.

And remembering.

An integral facet of my and Sari's friendship was writing. We befriended one another just as the call to reflect on reality through prose, poetry, story, and letters began.

Throughout this section of the memoir, I have collected some of those texts. Some mention Sari; some are coauthored with her. A favorite pastime of ours was to scribble thoughts down together when we were separated from one another in class.

One time, while stuck in detention for an entire day, Sari wrote me a seventeen-page letter. I still have it.

Several pictures of a young Sari in GIF form.

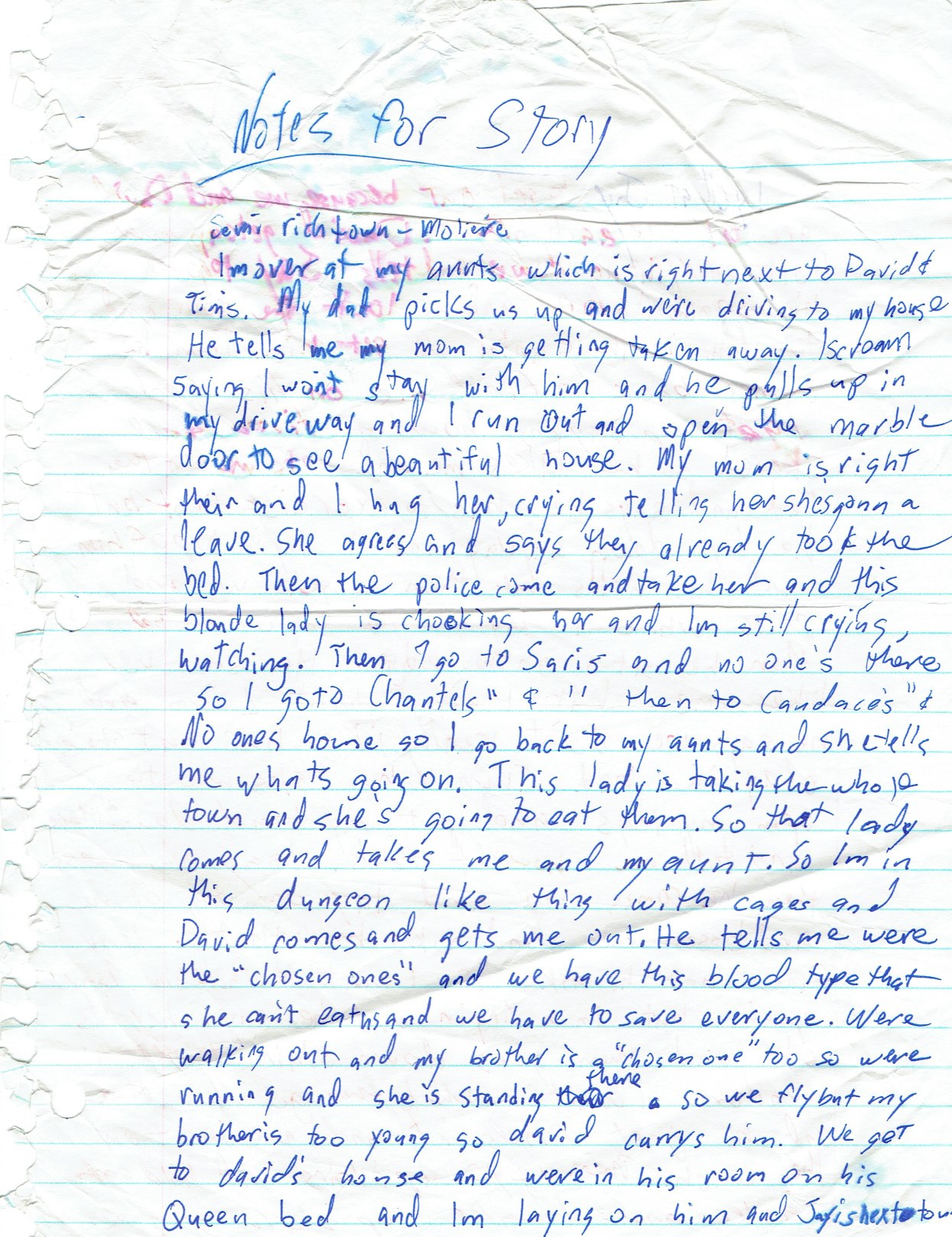

Scribbled notes of a story I had written in junior high.

Sari and I pose with a group of friends on the last day of junior high.

Sari and I met in elementary school, but it wasn't until eighth grade of junior high that we became best friends. We bonded over feeling like outcasts in our divorced families and our mutual love for alternative music. During many nights of ogling Jordan Catalano from My So-Called Life and rocking out to Hole's Live Through This, Sari and I would write poems and stories together, often fantasizing about many futures where we weren’t feeling crushed by our parents’ use of drugs and alcohol, or our poverty.

Clockwise from top left: Ray, Paul, me, and Sari. A photo booth.Summer 1995.

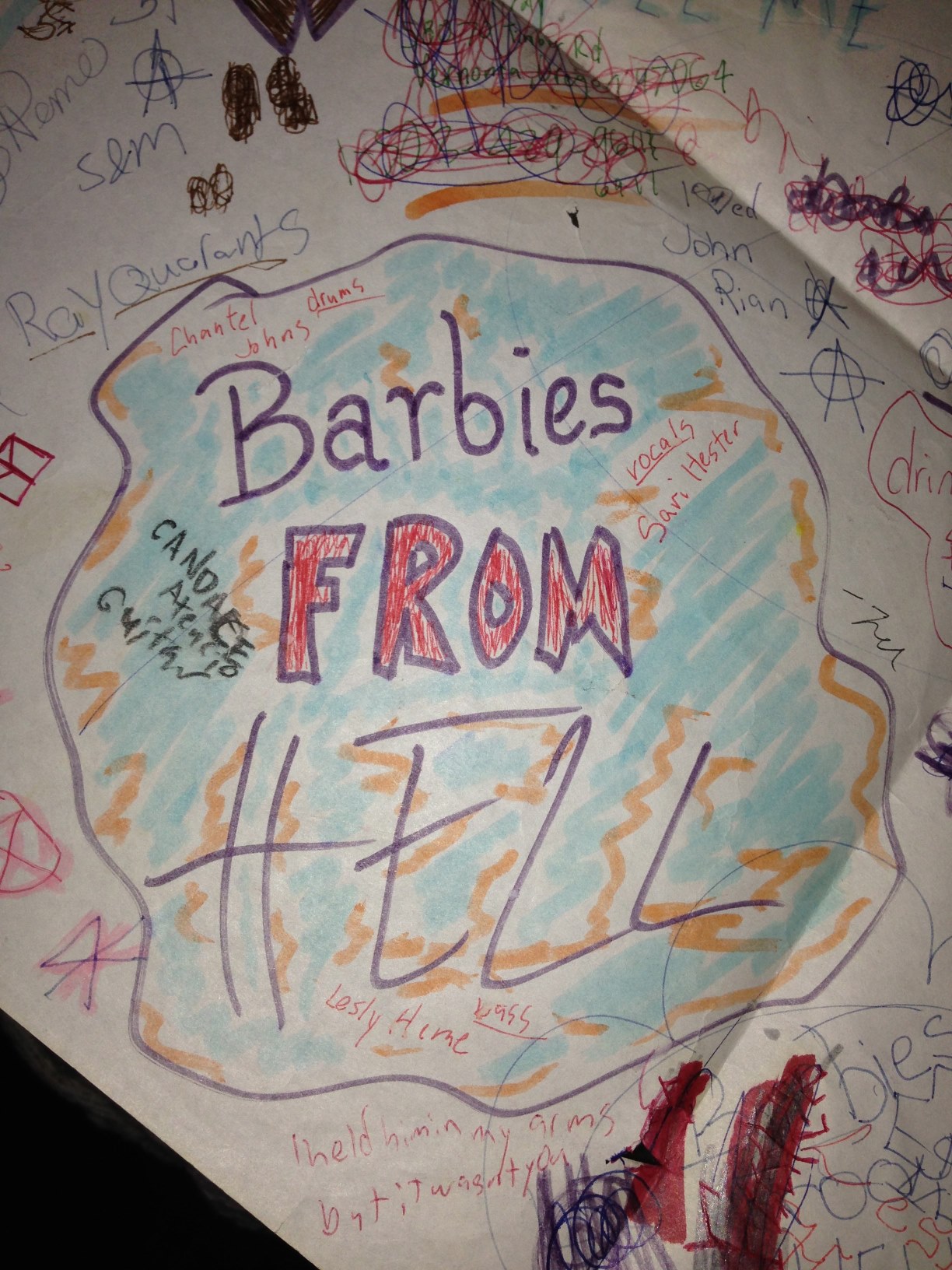

A drawing of our fictional girl punk band, Barbies from Hell. 1995.

A series of pictures taken in a photo booth.

Unison rave, Las Vegas. 2000.

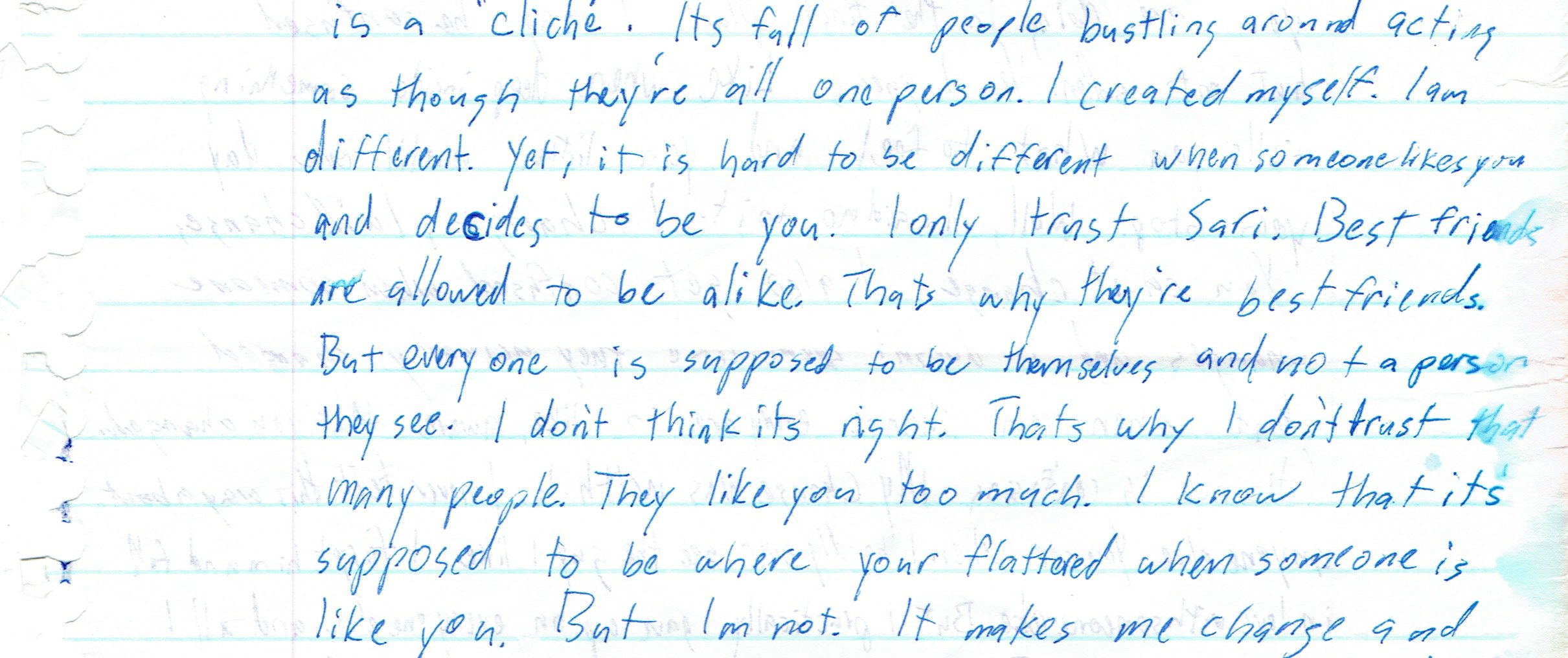

Journal entry. 1994.

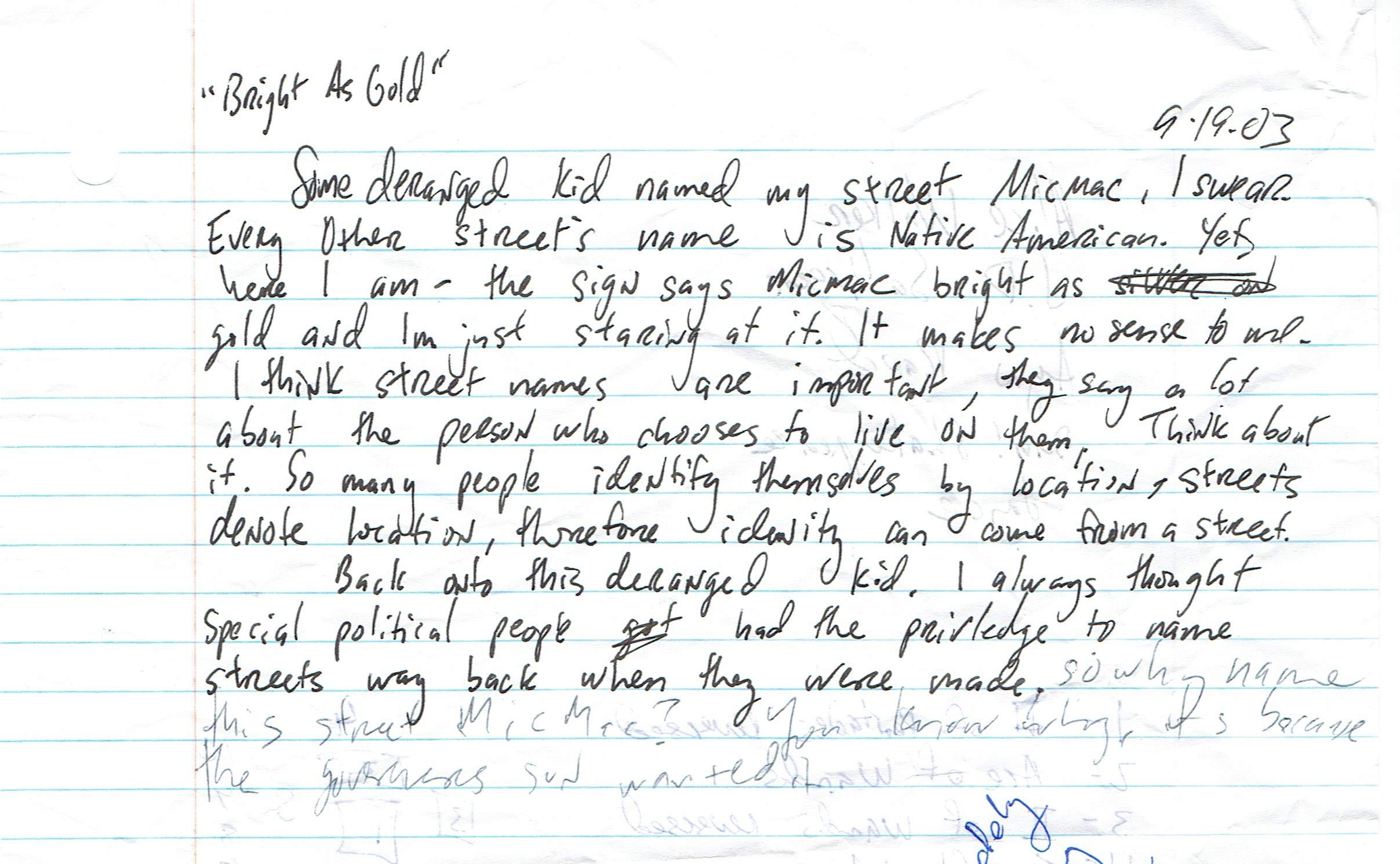

Journal entry. Micmac was a street we lived on together.

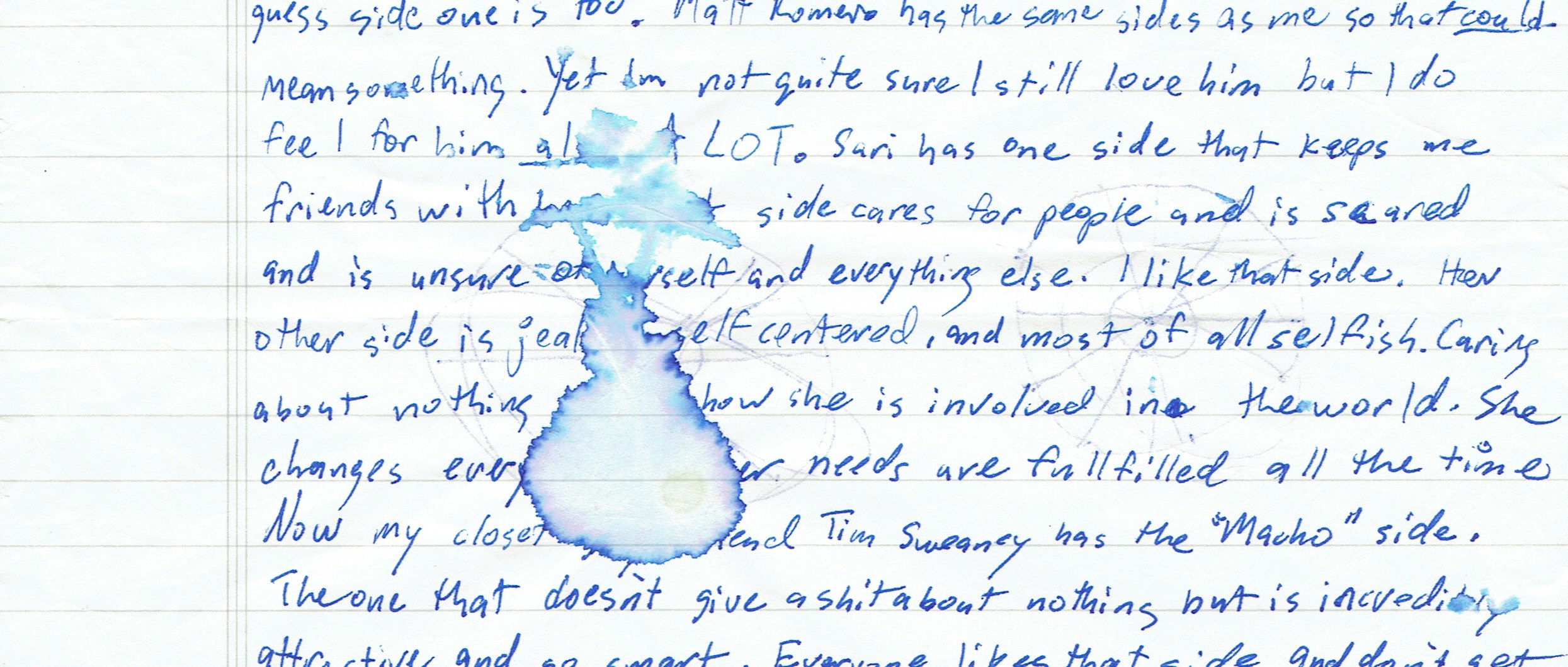

Journal entry. 1994. Sari's two sides.

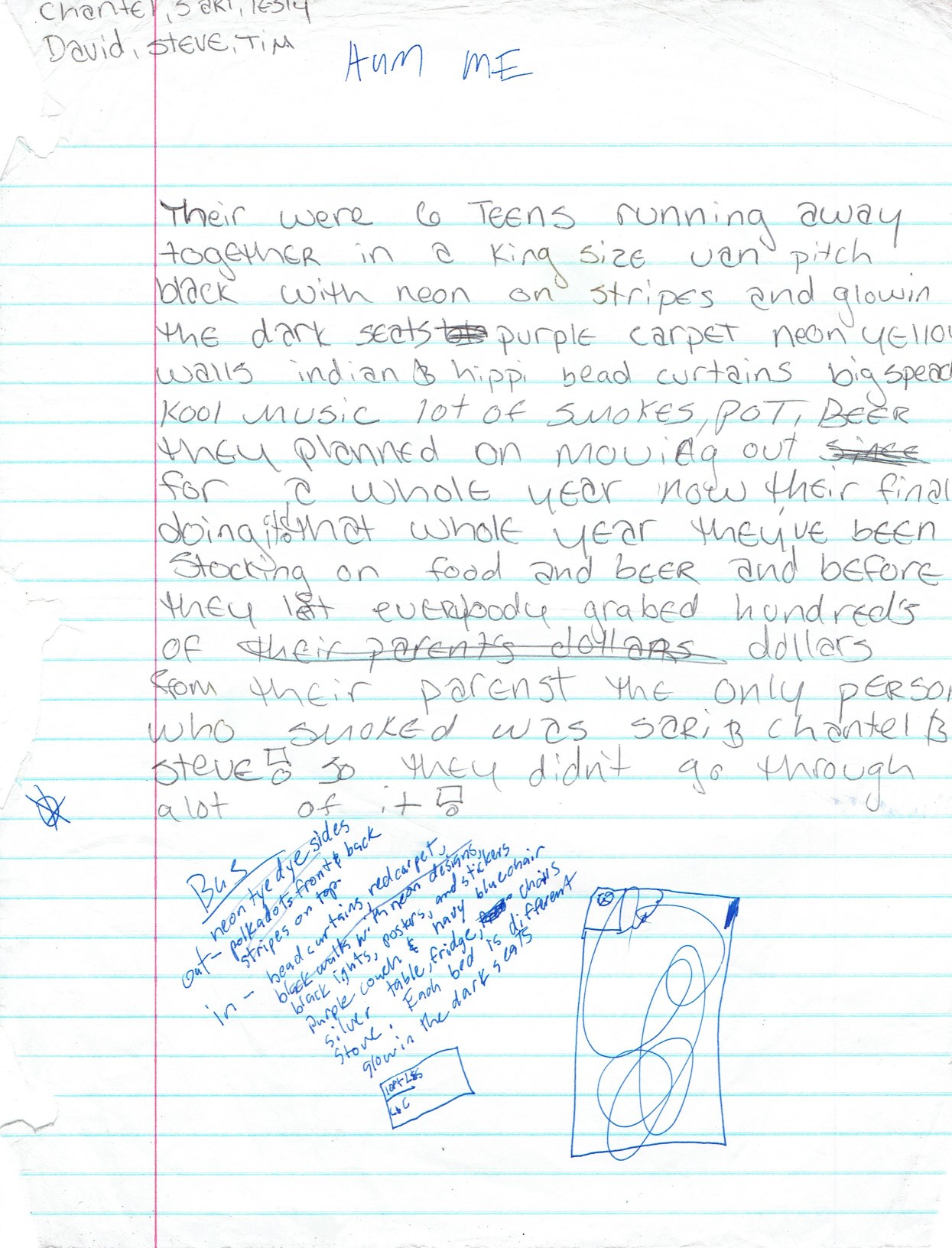

Sari's story about us running away. 1996.

Me, Sara, Sari, and Celia.

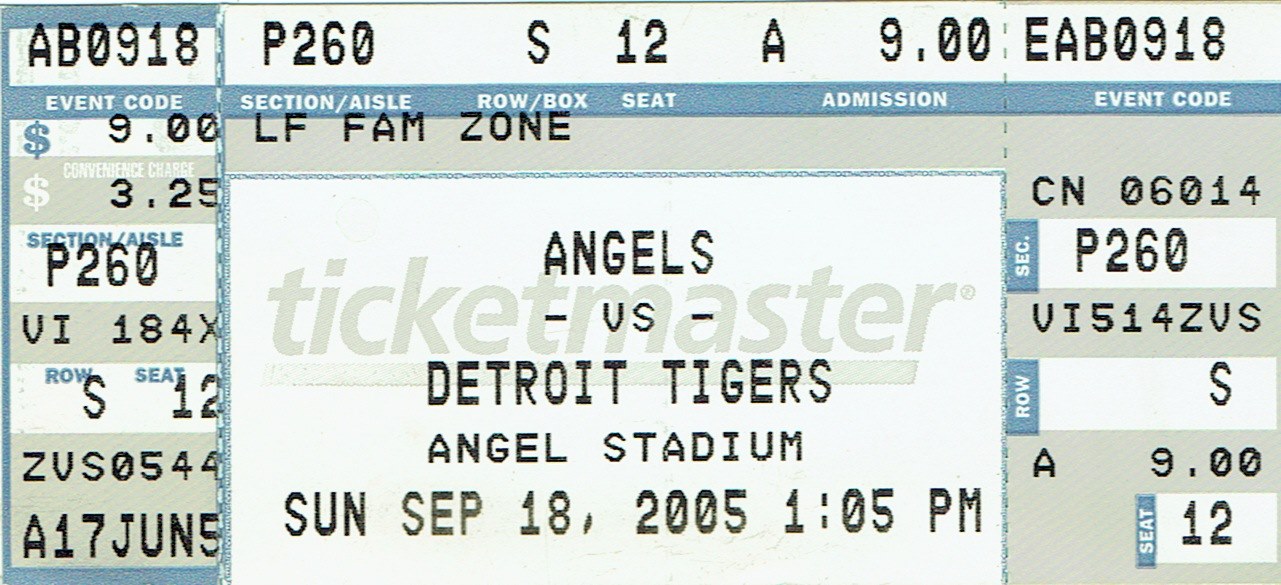

Sari the night before the Angels game.

Sari was with me the first night I drove my very first car and we parked in the country club parking lot. An old Hyundai Accent. It was a stick shift and I was a terrible driver.

***

Sari was with me a few weeks later when I wrecked that car. Bryson, Bryan, and Candace sat in the backseat, but that night, it felt like just me and Sari. We were driving down the main road in my hometown. It was dark, cool, but not too cold. February 13th, 1997. Friday, February 13th.

Bryan had his arm out the window, surfing the wind. Candace was giggling with Bryson. Sari and I were chatting. That’s when the left front tire of my car came off the axle. I overcorrected. We rolled over three times. Bryan just got his arm inside seconds before.

Everything went dark.

My eyes slowly began to open. I could see dust clouding around the cabin of the car, lit up by the light from the radio. I heard Sari softly singing Sublime. I began yelling in a panic,

“Sari, we have to get out of here! What if the car explodes?”

We both unlatched our seatbelts, which sent us falling on our heads. The car was upside down. We crawled out over broken glass and who-knows-what-else to get out the back window, or what was left of it.

Then, standing outside the car, Sari and I looked at each other: “We have to turn this over and get out of here before anyone sees!”

I remember looking up at a stream of cars lining up on the side of the road, their headlights making a line into the distance. They had seen us.

Me with Sari. Sari with Lilly. Sari with Candace.

Sari dancing with Chantel's brother at Chantel's wedding.

Chantel's bridesmaids: Sari, me, Janet.

The four best friends.

Sari had one of those smiles that lights up a room.

A laugh you could hear throughout the house.

We lived together off and on for the first five years of my adult life.

I was there for her during her pregnancy.

I was there for her daughter's birth.

I was there when her boyfriend beat her. She had called me at work and told me to come over, that something was wrong. I rushed right over. I saw her boyfriend holding her by her neck, choking her as her feet dangled inches from the floor.

I screamed at him to stop. He let her go and charged at me, his fist raised.

But he stopped right before he hit me. I did not flinch.

Ignoring him, I turned to Sari.

"Leave with me. Let's go."

She refused.

A few months later, Sari would move with that boyfriend to Arizona and never come back. She would die there, without me.

I would not be there.

Sari and Lilly at a Lorene Drive show. 2002.

Lilly, Sari, and Chantel at Sari's baby shower. 2000.

Returning to Wider, and connecting her with Hurlbert and Blitz, I see a methodology for writing that gets me to think about the personal archive as what helps us (re)construct a life. I think about how I am able to tell a story about loss because I have saved so many pictures and objects with which to remember the lives of my loved ones.

As I turn back to my plastic bins, my photo albums, my computer files—my archaeology of knowledge—I see pieces of my life unfold. I think about my children having access to these forms of storage and I see the importance of writing this story (and many after).

To write a story is to construct a history.

I hear Malea Powell from her essay "Dreaming Charles Eastman: Cultural Memory, Autobiography, and Geography in Indigenous Rhetorical Histories" in my head.

This is bigger than me.

I see a future without me in it. I begin to ask questions like,

- What other stories live in my archives of these two women?

- What violences am I erasing by writing this story?

- Who have I been archiving all these materials for?

I consider sending all of the pictures of Sari to her daughter, Alizabeth. I wonder how she will receive this memoir. I realize . . .

This is bigger than me.

A Christmas photo from Sari.

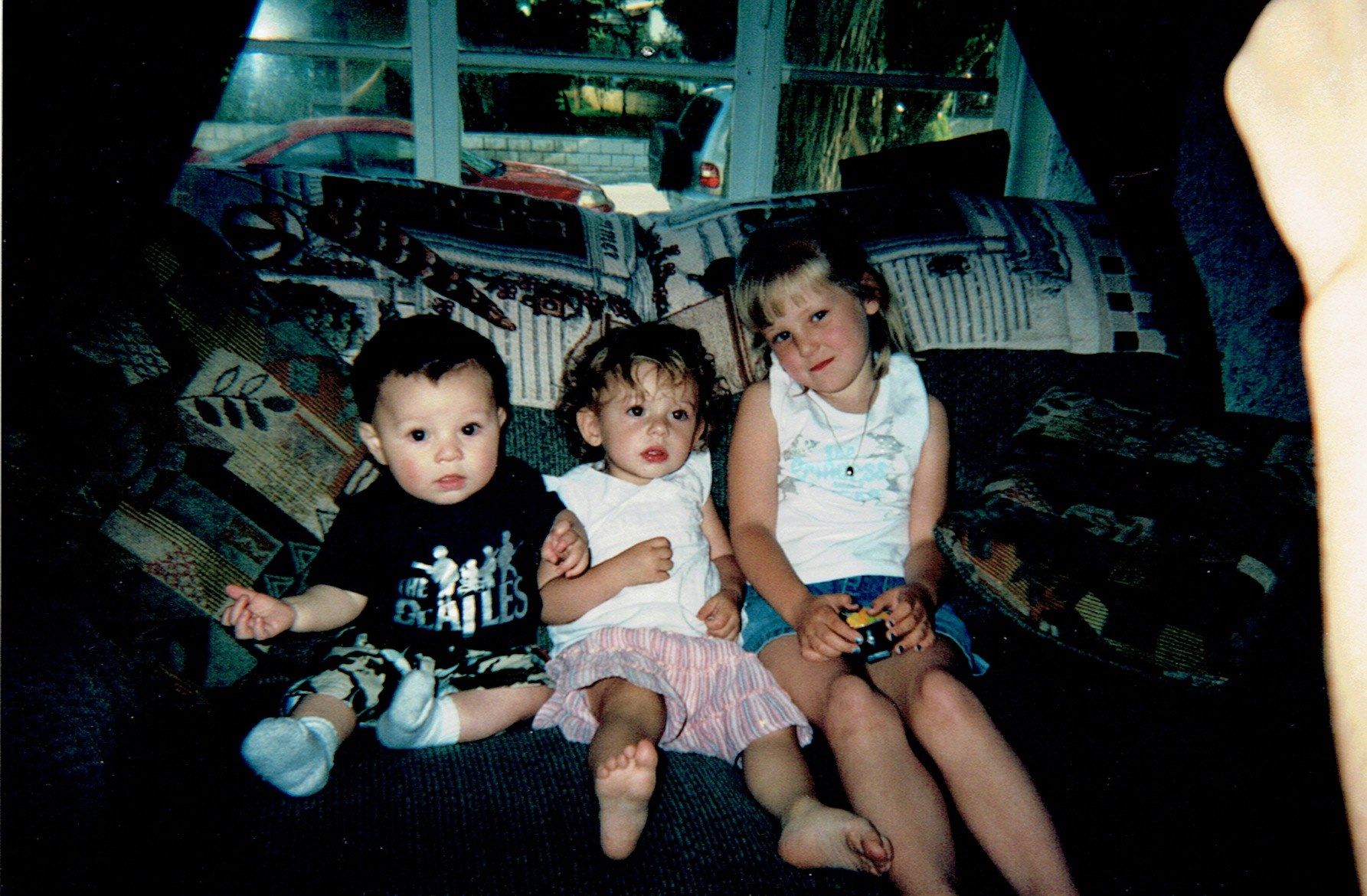

My son, Ben; Chantel's daughter Camryn; Sari's daughter Alizabeth.

Sari left behind a beautiful daughter to carry on her legacy—to remember her. Liz will surely have her own stories and maybe even write her own memoir one day. But, for now, this section is for her.

Alizabeth.

This memoir leaves me questioning:

How do we pass on the archives in our bodies to our children?

Evoking the Act of Memorializing

I return to my thoughts about the archive, my archive, and the politics that are carried within them. Powell writes of “the epistemology of the letter” or “the thingness of meaning” (115) as a reminder to attend to the effects of the marks and how meanings die when put to print. A shudder runs up my spine as I recall the histories my body carries, the archive that cannot be read.

No story will be more real than the one my skin can tell.

But my skin, does not speak in words; it writes its story through memory and emotion. So, going back to the question: how do we pass on the archives in our bodies to our children? How do we make a memoir meaningful to the people who death leaves behind?

I cannot offer a perfect answer for either of these questions. Instead, I want to focus on evoking the act of memorializing as an epistemology that makes knowledge known through embodied experience. To come to know by moving and doing.

As I remember my grandmother and my best friend, I begin a process of learning about their lives in a different way than I have known them while they were alive.

I have learned more about the lives of my family by how they were shaped by my grandmother. I have learned how my best friends and I will lean on one another through the loss of our best friend. But, most of all,

I have learned how to lose people I love.

Through the process of composing this memoir on loss, I have learned that remembering--memorializing—is a healing process that has taught me how to live on when people I love die. Because people I love will die. That truth is a fundamental part of living (to loosely paraphrase Hurlbert and Blitz).

It has taken me these last few years to realize this truth, but is a realization that I needed to have. And we all will need to have this realization eventually.

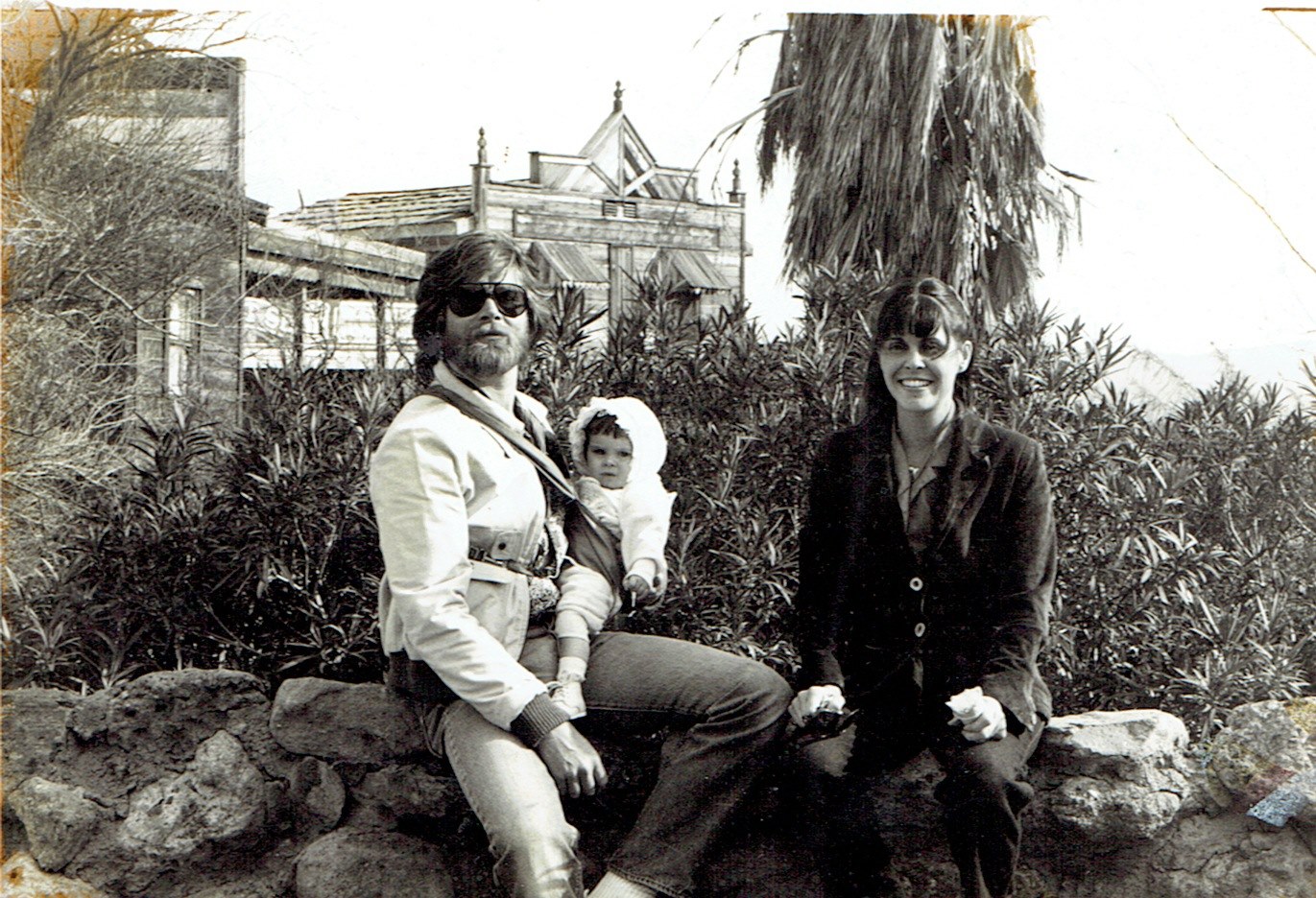

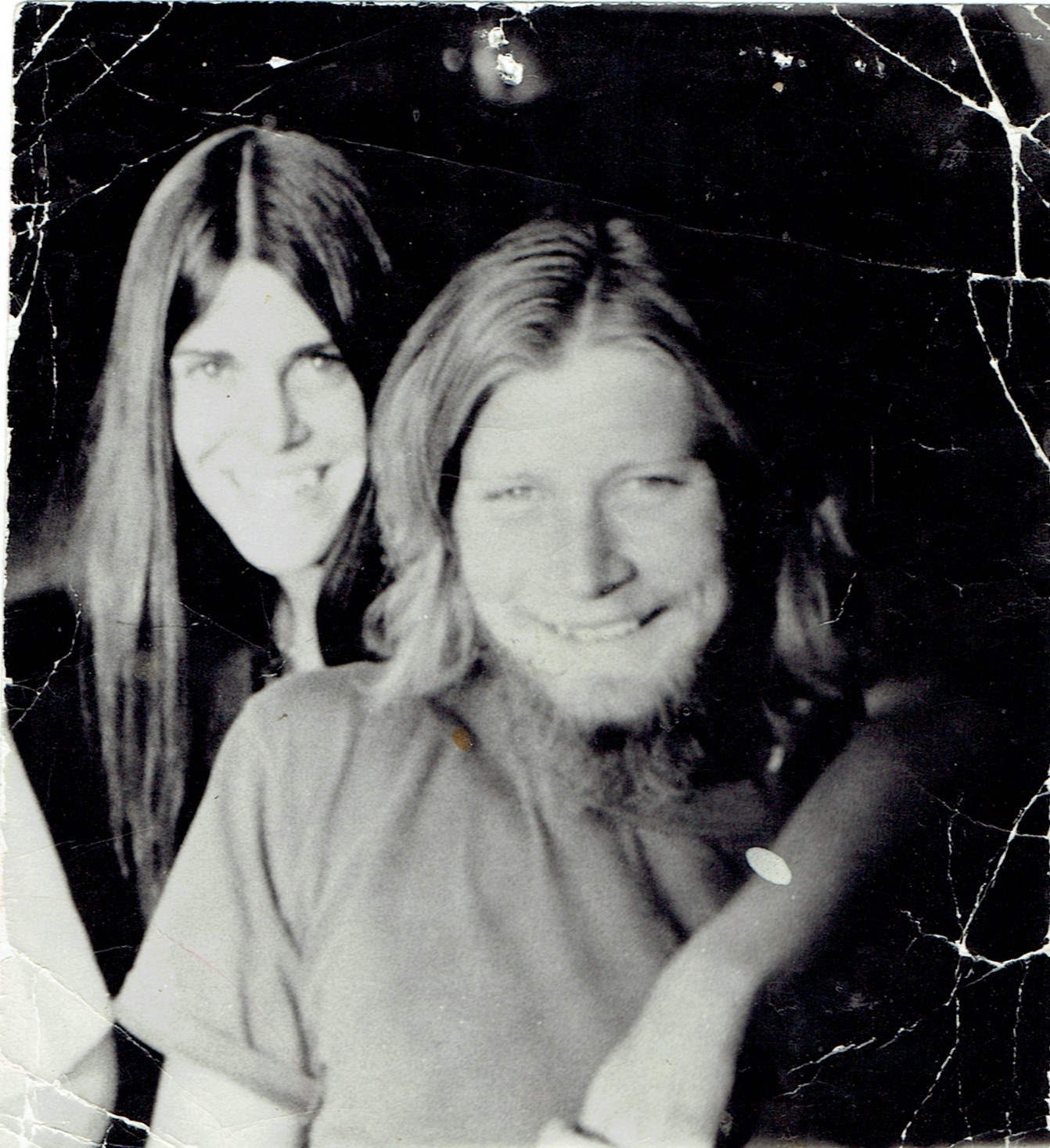

My parents. Photographer unknown. Year unknown.

The Body, the Land, and Academic Placelessness

To work with loss demands an attention to the relationship between my body and the objects that orient me to remembering the lives of those I have lost. As I theorize the loss of my grandmother and my best friend, I realize how significant a role the land plays in my orientation to memory. To physically touch the world manifests an engagement with healing. Unfortunately, I live far from home, far from the land that holds my memories.

The land of Joshua trees.

I began to compose this memoir in the deep recesses of my unconscious once I read Ashley J. Holmes’s “The Essence of a Path.” In her Finding Place section, she reflects on the act of experiencing a sensation of placelessness after moving to Tucson, Arizona, to start her PhD. Holmes's desire to make roots there, in the desert, prompted the writing of her article." Holmes forced me to think about my own placelessness, how leaving home brings back a desire to remember not just the lives of my grandmother and Sari, but the land where I made memories with them.

While I have been away, I have used social media to connect with friends and family and also as a source of scholarship where I have thought about the opportunities for embodiment in digital social spaces ("Writing to Have No Face"). It is with this work in mind that I reconsider the video I made, "What Does Being a Body Mean," as a representation of how I have used Snapchat videos as embodied epistemology.

This video shows captured moments pulled from everyday experiences that my body has had while I have grieved the loss of my grandmother and best friend. I compiled them into a cohesive narrative that reflects a poetic interpretation of healing. I screen the word RISK throughout the video as a thematic element that expresses how engaging as a body in the physical world after experiencing grief takes a considerable amount of courage. The short clips of video taken from Snapchat emphasize the hands-on, in-the-moment, and revolutionarily advanced ability of our current technologies to capture these everyday moments. Shifting between portrait and landscape views, the clips expose their being snapped on the fly.

Marc Santos speaks about the role technology played in his and his wife’s coping with their daughter’s diagnosis of retinoblastoma, a life-threatening eye cancer. He uses reflection on an interaction with another mother who also went through the same debilitating experience with her own daughter to think about the ways in which social media was instrumental for his coping. I too have turned to social media to cope with my traumatic experiences of loss.

The video and still images of flowers, leaves, and the sky throughout this memoir highlight how I used Snapchat to work with loss. Essentially, these images and videos have made Snapchat a place where I can be there.

Press to play.

As I shared bits of memories written out, images, and videos on social media, I engaged in an act of remembering as a form of visual narrative. To do so was an embodied act of memorializing —one that foregrounded the experience of remembering as a function of composing this memoir. This process also makes way for healing.

Both my age and my apprentice-level status in academia call into question the capacity in which a memoir can be written from my particular subject-position. I have been asked by our thoughtful editor and reviewers who saw previous versions of this text and offered their keen eyes for its revision to address: what does loss do to scholarship, particularly for a young scholar?

I realize the memoir as a genre is generally saved for late reflections from the sunset period of one's life and that this generic tradition holds, for the most part, valid. But as Cynthia G. Franklin determines in Academic Lives: Memoir, Cultural Theory, and the University Today:

"The free play and seeming frivolity that accompanies the genre constitutes not grounds for its critical dismissal but engagement: academic memoirs provide not only an index of scholars' lives and why they matter, but also unparalleled ways to catch the currents that define the U.S. academy" (2).

Franklin's words here give me (and all the women in this series, for that matter) space in which to compose ourselves as women, as feminists, and as relatively young scholars. We seek to bring into conversation issues graduate students have and continue to face through the form of memoir and storytelling.

If anything, I want to emphasize that I seek not the egotistical platitude that my own memoir here stands alone as some new text with which to disrupt the genre. Rather, I see myself carefully and respectfully constructing this text with an awareness of its other textual relations. Texts like Sharer's "Traces of the Familiar," Wider's "In a Treeless Landscape," and Powell's "Dreaming Charles Eastman" have inspired my thinking. Theirs are this text's relations. I learn from these women who wrote about navigating loss and theorized through story the ways in which loss not only impacted but formed their research. It is alongside them that I speak and write.

Sharer's suggestion that we draw on the affective connections we have with our research projects in itself led me to the creation of this memoir. She says,

I hope that, by presenting my story, I can foster a desire in future scholars to explore the rhetorical practices of family members and friends and, at the same time, to counteract the restrictions an assumptions that place family and friends—"personal relationships" and the affective domains that surround them—beyond the boundaries of valid research. (55)

And the presentation of her story, indeed, encouraged my initial questions about the affective and rhetorical practice of loss as a person who, like others in our early- to mid-thirties, would start experiencing the death of our loved ones. The truth is that many of us have had this experience.

I hope that, by presenting my story alongside the stories in this collection and the stories I have cited, I can encourage future scholars to take their time when grieving lost loved ones and to find a way to write through their pain and create for themselves their own memoirs about loss. Funerals need not be the only Western memorializing practice we have for the living.

An ofrenda honoring my grandmother and Sari I made for Día de los Muertos 2016.

I conclude this memoir with several enacting evocations:

I think about my grandmother, a woman who composed her life around her family. A matriarch. A single mother. A working mother. Remembering Shirley Hutchinson teaches and reteaches me about the role my academic success plays in the narrative my family will tell.

I come from a long line of strong women.

I think about Sari. We were supposed to grow old together. We once joked about living in a nursing home and sharing a room. We had dreams of living near the ocean. Those dreams are not dead; they are forever buried there.

I have learned how to speak in waves.

A squash flower from my garden weeks before I left California.

Works Cited

Franklin, Cynthia G. Academic Lives: Memoir, Cultural Theory, and the University Today. U of Georgia P, 2009.

Holmes, Ashley J. “The Essence of the Path: A Traveler’s Tale of Finding Place.” Kairos, vol. 16, no. 3, 2012, http://www.u.arizona.edu/~ajholmes/finding_place.html. Accessed 6 Nov. 2018.

Hurlbert, Claude Mark, and Michael Blitz. “Equaling Sorrow (A Meditation on Composition, Death, and Life.” Composition Studies, vol. 31, no. 1, 2003, pp. 83-97.

Kirsch, Gesa E., and Liz Rohan, editors. Beyond the Archives: Research as a Lived Process. Southern Illinois UP, 2008.

Murray, Joddy. Non-Discursive Rhetoric: Image and Affect in Multimodal Composition. SUNY P, 2009.

Powell, Malea. “Dreaming Charles Eastman: Cultural Memory, Autobiography, and Geography in Indigenous Rhetorical Histories.” Kirsch and Rohan, pp. 115-127.

Rhodes, Jacqueline, and Jonathan Alexander. Techne: Queer Meditations on Writing the Self. Computers and Composition Digital P, 2015, https://ccdigitalpress.org/book/techne/. Accessed 6 Nov. 2018.

Santos, Marc C. “How the Internet Saved My Daughter and How Social Media Saved My Family.” Kairos, vol. 15, no. 2, 2011, http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/15.2/topoi/santos/index.html. Accessed 6 Nov. 2018.

Sharer, Wendy B. “Traces of the Familiar: Family Archives as Primary Source Material.” Kirsch and Rohan, pp. 47-55.

Wider, Kathleen. “In a Treeless Landscape: A Research Narrative.” Kirsch and Rohan, pp. 66-72.

Wysocki, Anne Frances. “Seriously Visible.” Eloquent Images: Word and Image in the Age of New Media, edited by Mary E. Hocks and Michelle R. Kendrick, MIT P, 2003, pp. 37-59.

*All images and writing other than those cited above are the property of Les Hutchinson.

**However, much of this ongoing memoir has been inspired by other works read in Alex Hidalgo's Academic Memoirs Across Media course.

Hidalgo | Chambers | Hutchinson

Shade-Johnson | Brentnell | Leger

Braude | Sweo | Nur Cooley

__________________________________

Intermezzo, 2018