Alisdayhv is a Cherokee term that means, essentially, "come and eat."

At family gatherings, I was the kid who was always helping my mom and grandmothers in the kitchen rather than playing outdoors with my cousins, so my job was to call my relatives in to eat. I would run up to the groups of cousins, uncles, and aunties, interrupting their conversations to yell "alisdayhv!" before running off to alert the next group. I have a big family. It took some time and repetition to relay the message.

For me, alisdayhv means more than simply an invitation to eat; it reminds me of my connections and responsibilities to my family and to my community. It reminds me of the loving work of putting meals on the table, and of the cultural practices that bring us all together.

Me, Grade 3

In her book Kaandossiwin: How We Come To Know, Anishinaabe kwe scholar Kathleen E. Absolon explains that “Meaning making is what we do with knowledge, and when we gather berries, we make meaning of those berries by making jam or pies and then we share all that we have gathered with the people” (22).

Through this project, I aim to make meaning of the foodways of my Cherokee family by sharing some of the stories, recipes, and food-based knowledges that have been shared with me. This memoir project is a compilation of my family photos, stories, histories, and recipes that traces the roots of my invested interests in the rhetorics of Cherokee foodways. Supplemented with photos and video clips, Creative Commons licensed images, and maps, I rely on the theoretical and methodological framework of Luce Giard and Kathleen Absolon to guide me along the way.

In The Practice of Everyday Life Volume 2: Living & Cooking, author and theorist of everyday practice Luce Giard explains, "The nourishing arts have come down to us from the depths of the past, immobile in appearance in the short term, but profoundly reworked in reality over the long term. Provisions, preparation, cooking, and compatibility rules may very well change from one generation to another, or from one society to another. But the everyday work in kitchens remains a way of unifying matter and memory, life and tenderness, the present moment and the abolished past, invention and necessity, imagination and tradition—tastes, smells, colors, flavors, shapes, consistencies, actions, gestures, movements, people and things, heat, savorings, spices, and condiments" (De Certeau, Giard, and Mayol 222).

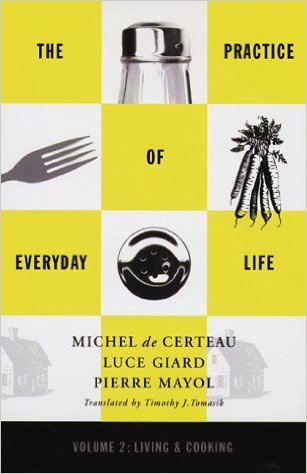

When I was born, my grandfather, Leonard (Galemi) Shade, named me ᎢᏯ (Iya), which means pumpkin in Tsalagi, the Cherokee language, because of my big, round, orange head. Pumpkin is variant of squash, one of the "Three Sisters" in Native food traditions, along with corn and beans, so it seems fitting that I am interested in food practicets within my tribal community.

Me as a newborn

Click the image for a mini-lesson on the word iya from Osiyo TV

Work found at Tambako, FlickerCreative Commons By-ND 2.0

The story of how I came to study the rhetorics of Cherokee foodways, however, began long before I was born. In order to discuss my relationship with the food traditions that inform my research, I look to my grandfather, who carried cultural food practices from his parents, grandparents, and the ancestors who came before; then, in turn, he passed some of them to my father and his siblings, and some of that knowledge has filtered its way down to me.

The history of my family is tied to the larger history of the Cherokee people. In the time of the Cherokee Removal in the mid-1800s, my ancestors left their homelands (some voluntarily, some forcibly removed) in Georgia and North Carolina and made new homes in Cherokee Territory and in western Arkansas (Smithers 195; Ehle 328-44). About 50 years later, from 1887-1889, the Dawes and Curtis Acts, federal land policies, separated Cherokee communities by partitioning land and allotting tracts of the land to individual tribal members (Smithers 229-32). During this period in Cherokee history, which we call Allotment, these land policies effectively distanced Cherokee families from their clans, other relatives, and community-centric ways of life.

The Cherokees who had survived the Removal and Allotment periods found themselves, like many other tribes who faced similar displacements, without access to their traditional hunting and gathering places. Eventually, after starvation continued to impact tribal communities whose populations were already decimated by colonial diseases, forced diasporas, and other forms of settler violence, the US government began distributing rations called commodities. The commodities, which are still distributed today, supplemented the diets of cultivated fruits and vegetables, wild game, and foraged plants with rations of food staples of Western diets (such as flour, oil, and powdered chicken eggs). Unfortunately, commodity rations proved to be yet another tool of erasure and assimilation of Native peoples.

My great-grandmother, Annie (Smith) Shade

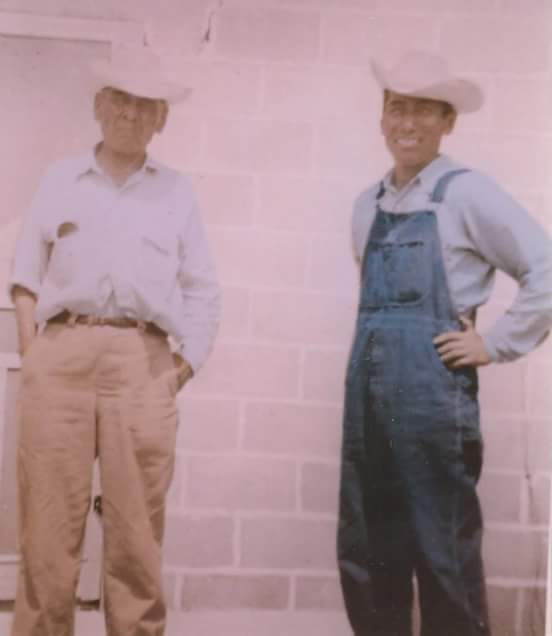

My great-grandfather, Albert Shade (right)

My great-grandparents' allotted homestead was located in Lost City, Oklahoma, a rural community near Tahlequah, the capital city of the Cherokee Nation.

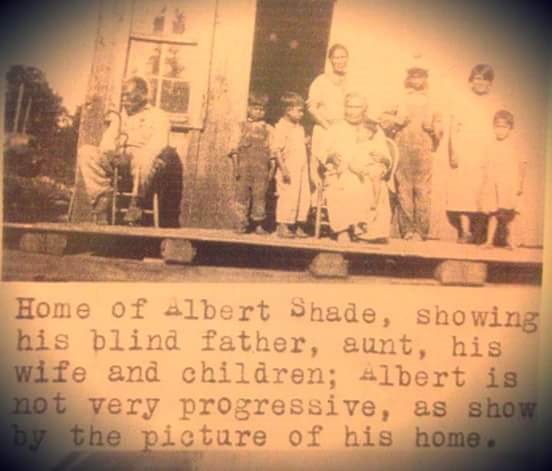

This newspaper clipping (right), recovered from an old photo album, depicts an image of my great-grandparents' homestead, captioned "Albert [my great-grandfather] is not very progressive, as show[n] by the picture of his home."

My grandfather built his home just down the road from his parents' homestead, where he and my grandmother raised their children.

Newspaper clipping showing the home of my

great-grandparents, Albert and Annie (Smith) Shade

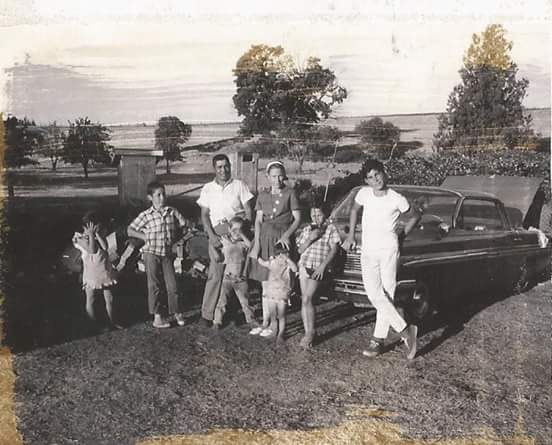

Leonard and Christine Shade with their children

.jpeg)

My father, Joe Shade, as a child

My grandfather on his front porch

It is through this long heritage of family and food that my story as a researcher and practitioner of Cherokee foodways begins. Giard tells us, "Good cooks are never sad or idle—they work at fashioning the world, at giving birth to the joy of the ephemeral; they are never finished celebrating festivals for the adults and the kids, the wise and the foolish, the marvelous reunions of men and women who share room (in the world) and board (around the table)" (De Certeau, Giard, and Mayol 222).

Wishi (hen-of-the-woods mushrooms)

Photo by Flickr user

Theogren, Flickr

Help Yahoo! Search

I have only recently learned the Latin word for what my tribal community calls wishi: Grifola frondosa. This mushroom grows in forests across the Northern Hemisphere, including Europe, Japan, China, the United States, and Canada. The Japanese word for this variety of mushroom is maitake. In English, it is known as hen-of-the-woods, sheepshead, or ramshead.

Cherokees call it wishi. We view wishi as a delicacy, and it is present at most holiday meals and large family gatherings. When I think of this word, I think of my family. I think of my grandmother and grandfather walking out into the woods with baskets to collect the mushrooms from the bases of oak trees—always on the east-facing side. I think of my father, who generally dislikes all other mushrooms, who heads out into the woods on his own during the autumn months, returning to the wishi that he's been watching all summer until it is big enough to harvest.

My grandmother cleaning wishi

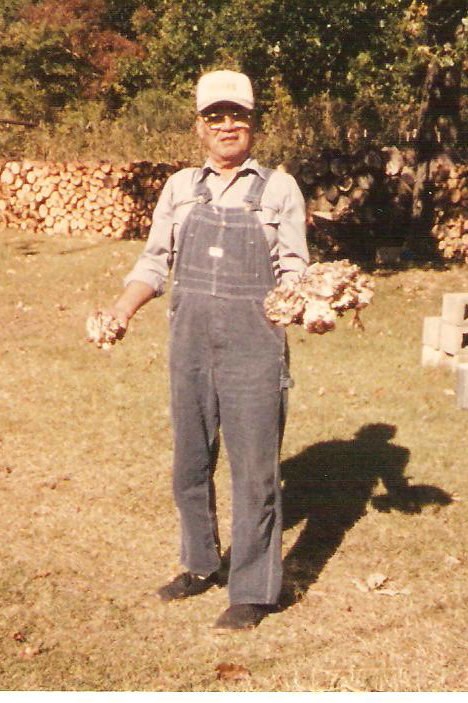

My grandfather holding wishi

There is a coded system for foraging wishi: A stake in the ground near it means that it is spoken for, that someone, like my father, has been tending to that wishi and has assumed stewardship over it. If there is no stake near the wishi, it means that it is available for gathering. It is considered an offense to take wishi that has been marked by someone else. Most Cherokees keep our "wishi trees" secret so that no other people will come and take the wishi that we've been tracking over a period of time.

Absolon considers the concept of "research" as a process of Indigenous ways of knowing:

"We gather berries, plants and herbs, and we hunt moose, deer, geese and ducks. We also trap rabbits, beavers and muskrats. We harvest food and medicines from the forest and earth, and the knowledge of how to do these things has been developed, shared and passed down from generation to generation. Terms that reflect Indigenous ways of collecting and finding out are searching, harvesting, picking, gathering, hunting and trapping.... It is the process of how we come to know" (21).

Wishi tree (Photo by Joe Shade)

My father, trained from an early age to hunt wishi, can instantly spot them from a distance, yet it takes me much longer to find them. He tells me, "Look over there," gesturing with his lips and chin. I look and look, and he'll laugh and watch me peering around at trees. I'm sure his parents were even better wishi hunters, and that their parents were better still. I wonder how long it will take my niece and nephew to find them, how the skills of wishi hunting will dwindle with each passing generation, and whether or not we will be able to revitalize these foodways traditions as we grow, both physically and culturally, ever further from the land.

Young wishi (Photo by Joe Shade)

Roasted Wishi

The sections that follow focus on two common foods for Cherokee peoples: wishi (hen-of-the-woods mushrooms) and svgi inage ehi (wild onions). Each section contains recipes that use these two foods, some of which also include Western ingredients. While I was initially inclined to reject those colonized recipes, I find that those in particular speak to the survivance ("survival" + "resistance") of the Cherokees and to our realities as contemporary peoples (Powell 400).

This recipe is a fairly healthy way of cooking wishi. The thyme could be substituted with sage for a completely Native dish.

What you need:

2-1/2 cups wishi

2 tablespoons finely chopped thyme

3 tablespoons sunflower oil

natural salt

ground black pepper

My grandfather holding wishi (Photo by Edna Shade)

What to do:

- Put the oven rack in the middle position and preheat the oven to 300 degrees F (150 C).

- Trim any tough bits of stem and then shred the mushrooms into small clusters. Put them in a bowl and toss with the sunflower oil and thyme.

- Line the clusters up in a single layer on a sheet pan and roast until the mushrooms are golden brown and crisp around the edges (50-60 minutes).

- Sprinkle with salt and pepper to taste, and serve immediately.

Yield: 2-3 servings

Fried Wishi

Fried wishi (Photo by Edna Shade)

What you need:

3 cups wishi (cleaned, trimmed, and chopped)

1 cup all-purpose flour

plenty of oil (for frying)

plenty of water (for boiling)

natural salt

ground black pepper

Preparing the wishi (Photo by Edna Shade)

Photo by Flickr user evefox, Flickr Help Yahoo! Flickr Search

Every holiday, we have a big bowl of fried wishi on the table. This is the most common preparation method for wishi in contemporary Cherokee communities. This method of preparing wishi is one that results directly from oppressive land-based policies of the United States government. Fried wishi is typically prepared using commodity flour and oil.

Frying the wishi (Photo by Edna Shade)

What to do:

- Partially fill a large soup pot with water and boil.

- Add wishi.

- Boil until wishi is softened and tender; drain and set aside.

- Heat a frying pan with oil.

- Add flour to a bowl and toss wishi in it until coated.

- Slowly add wishi into frying pan, taking care to not crowd the

pan.

- Fry until crispy and golden.

- Sprinkle with salt and pepper to taste, and serve immediately.

Yield: 4 servings

Svgi Inage Ehi (wild onions/ramps)

Land policies that impact our foodways continue into the present day. The exerpt below is from the opening statement of defense attorney James Kilbourne on November 23, 2009, in U.S. v. Burgess, a case in which a citizien of the Eastern Band of the Chrokees had been charged for foraging ramps in a national park:

''[T]he Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and Cherokees have been harvesting ramps in this area for over 10,000 years. You're going to hear testimony, your honor, about this particular land—this land where the park is presently located where these incidents occurred—which was part of the traditional Cherokee homeland . . . And you're going to hear about the ramps [and] the traditional method that [the Cherokee] use to harvest these particular plants . . . So, your honor, I believe that when we're through, I'll be able to make to you the legal argument that the Cherokee have an easement that allows them to take [ramps] and that they have not just a legal right, but a moral right to do so as one of their inherent cultural rights as native Cherokee people" (qtd. in Lewis 104, , ellipses are Lewis’s).

Photo from Wikimedia, Conniemod

(licensed under Creative Commons attribution)

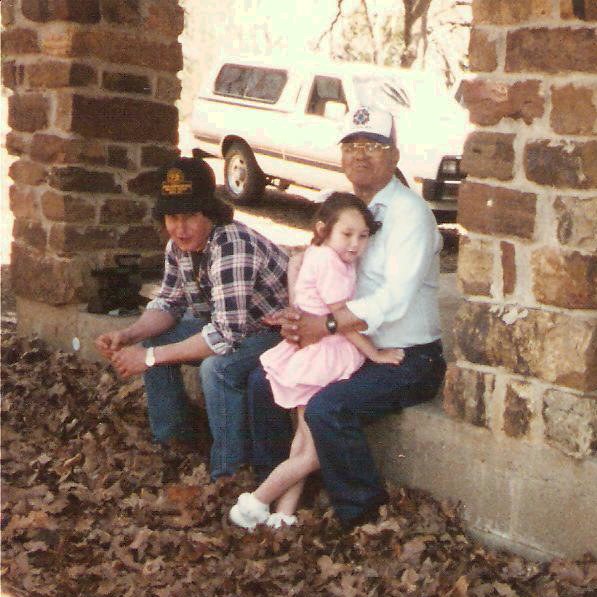

From left, my uncle, Albert Shade,

me, and my grandfather

My grandparents used to take me with them out to wooded areas to gather wild onions and wild garlic. We would each carry a plastic or paper grocery sack, whatever they had on hand, and we would walk around, stopping every so often to harvest onions from the earth. My grandfather showed me how to use his pocket knife to cut off the stems and the top of the bulb before patting a little bit of dirt back over the rooted bulbs that we left behind so that they would grow again. Then, he would leave some tobacco behind as an offering to the land.

I cannot think of wild onions without thinking of my grandfather. While I was growing up, my grandfather always made sure to have a plate of fresh wild onions on the table at mealtimes. He ate them uncooked alongside his meal, as most of us do with bread.

Even as a young child, I enjoyed eating onions, both wild and store-bought bulb varieties, so I loved working with my grandparents to gather them for meals.

"Wooo-weee!" my grandfather would say, "Jaquetta Leanne, you shore picked a lot of onions!"

I still remember the pungent onion-y smell on my hands afterward.

Eggs and Wild Onions

Work found at

evefox, Flickr

Help Yahoo! Search

Eggs and wild onions is common Cherokee food. It can be cooked with chicken, goose, or duck eggs and foraged wild onions. If fresh eggs are not available, commodity eggs, or dry powdered eggs, will do.

What you need:

2 dozen wild onions (rinsed and trimmed)

2 tbsp. water

6 eggs

1 tbsp. butter

natural salt

ground black pepper

What to do:

- Coarsely chop the onions.

- Melt butter in a skillet over medium heat.

- Add onions and water, then sauté until onions are limp.

- Add eggs.

- Scramble eggs with onions.

- Add salt and pepper to taste, and serve immediately

Yield: 4 servings

Rhetorical Foodways

In The Practice of Everyday Life, Volume 2, Luce Giard explains, "from the moment one becomes interested in the process of culinary production, one notices that it requires a multiple memory: a memory of apprenticeship, of witnessed gestures, and of consistencies, in order, for example, to identify the exact moment when the custard has begun to coat the back of a spoon and thus must be taken off the stove to prevent it from separating" (De Certeau, Giard, and Mayol 157).

What Giard describes here as a "multiple memory" of cooking I see as an embodied cultural literacy. Now that I live in Michigan for graduate school, far away from my mother, I find myself fumbling in the kitchen as I attempt to cook by myself the foods that I have helped my mother and grandmothers cook in the past. She, as my grandmothers before her, makes swift, accurate, and nimble movements when handling the food. My hands are clumsy in the kitchen, while my mother's hands are agile and deft. They know what to do—they have the memory.

This "multiple memory" is fundamental for the practice of Cherokee foodways and our stewardship of the land. Our everyday food practices are part of a much larger narrative. This project has shown me that there is space for more expansive research on how we Cherokee peoples make meaning through our food. I see in our foodways deep connections to other Indigenous concerns, including reciprocal relationships with the land, how these practices are decolonizing acts of survivance, and how they promote Native food sovereignty. This project is both an exploration of my personal and academic positionality and a springboard from which I enter into scholarly discourses about the concerns facing my community and Indigenous peoples everywhere.

Works Cited

Absolon, Kathleen E. Kaandossiwin: How We Come to Know. Fernwood, 2011.

De Certeau, Michel, Luce Giard, and Pierre Mayol. The Practice of Everyday Life, Volume 2: Living & Cooking. U of California P, 1998.

Ehle, John. Trail of Tears: The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation. Anchor Books, 1988.

Lewis, Courtney. “The Case of the Wild Onions: The Impact of Ramps on Cherokee Rights.” Southern Cultures, vol. 18, no. 2, 2012, pp. 104-117.

OsiyoTV. “Wild Onions, a Cherokee Foraging Tradition.” YouTube, 12 Apr. 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gUL7I7OtPS8. Accessed 7 Nov. 2018.

Powell, Malea. “Rhetorics of Survivance: How American Indians Use Writing.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 53, no. 3, 2002, pp. 396-434.

Smithers, Gregory D. The Cherokee Diaspora: An Indigenous History of Migration, Resettlement, and Identity. Yale UP, 2015.

Visit Cherokee Nation. “CHEROKEE WORD OF THE WEEK: PUMPKIN.” YouTube, 13 Oct. 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HNCsP5UpgXE. Accessed 7 Nov. 2018.

Hidalgo | Chambers | Hutchinson

Shade-Johnson | Brentnell | Leger

Braude | Sweo | Nur Cooley

__________________________________

Intermezzo, 2018