Call: Sheeko sheeko.

Response: Sheeko xariir.

When I travel at night I have this habit of looking for the moon, even

when I know it's on the other side of the world. Even when I know I

won't see it. But when I do see it – those moments when the sky I

look up at matches the sky of my memories – I'm taken back to the

many times I've stared out the window of a car/train/bus/plane on

the way to somewhere.

I then also hear the faint sound of my mother singing huuwaya

huuwa – lulling me. I am orienting myself in the cocoon of my

memories – my homes.

I guide you to the words of Royster and Kirsch in Feminist

Rhetorical Practices: New Horizons For Rhetoric, Composition,

And Literacy Studies as an example of why I am making these moves in my scholarship. I engage you in what they call a "whole-body experience," inviting all those reading, listening, or scrolling "to engage in a process of strategic contemplation, using their critical imaginations to get inside of a moment of critique and productivity; to look around, think about what they are seeing and thinking, and come to a new level of understanding; to use this base of information for reflection, speculation, talking about writing, writing, and critique" (97).

I remind you. This thesis is a narrative. A digital presentation. A

performance. A story. One situated specifically in my own

experiences as a woman of the Somali diaspora – one filled with

much movement, migration, and memory.

When I speak of movement and migration in this text and context, I understand the complexities connected to my choice of words.

However, I intentionally dissociate movement from migration. I

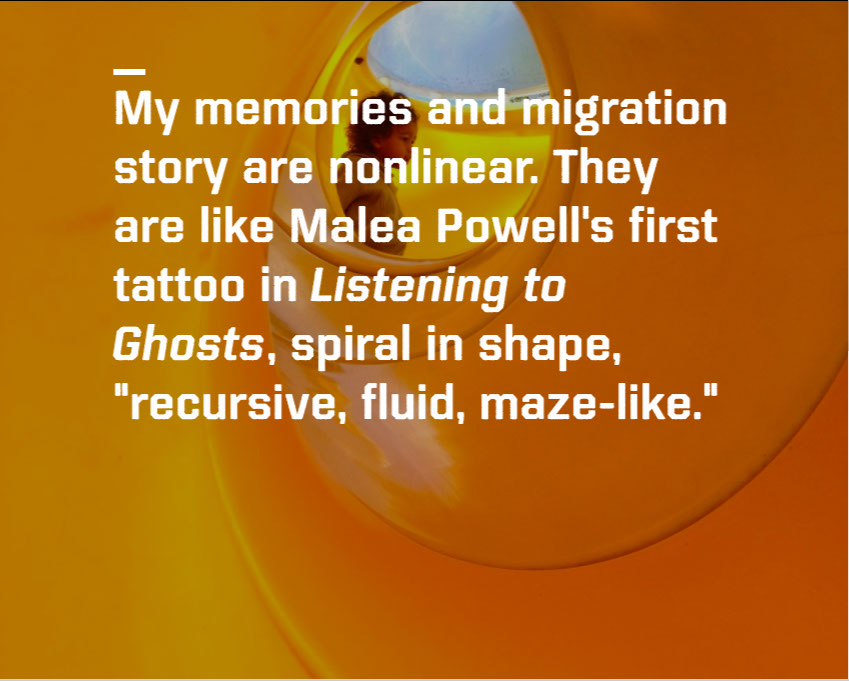

And in the same way that Powell's tattoo denotes meaning in both what is and what is no longer, this narrative will also represent "another set of meanings delineated by dis- and re-appearance" (13). I will leave spaces, as Powell states, "to mark the presence of absence" (18). Whether it is in the absence of memory, of story, or of people – I leave room for the ghosts to speak.

In Techne, Jacqueline Rhodes and Jonathon Alexander discuss the ways in which those in the field of rhetoric and composition have used personal narratives to interweave with theoretical conversations, utilizing their own lived experiences to theorize and connect the personal with the political.

In Techne, the writing of the self also "attempts both to map out and to provoke visceral awareness of the interimbrication of bodies and technologies, orienting and reorienting one another" ("Introduction"). To me, the personal and political are inseparable, and the culmination of my experiences and orientations are – in themselves – disorienting.

I want to use my own experiences to situate others in what Ahmed would consider the queer orientation of my lived experience, "a way of inhabiting the world by giving "support" to those whose lives and loves make them appear oblique, strange, and out of place" (179). I will do this by using a multimodal, performative approach at attempting to orient your bodies with my experiences and memories, reorienting you only when something is familiar – whether it is through the technologies used, or the experiences/stories in my narrative you can relate with.

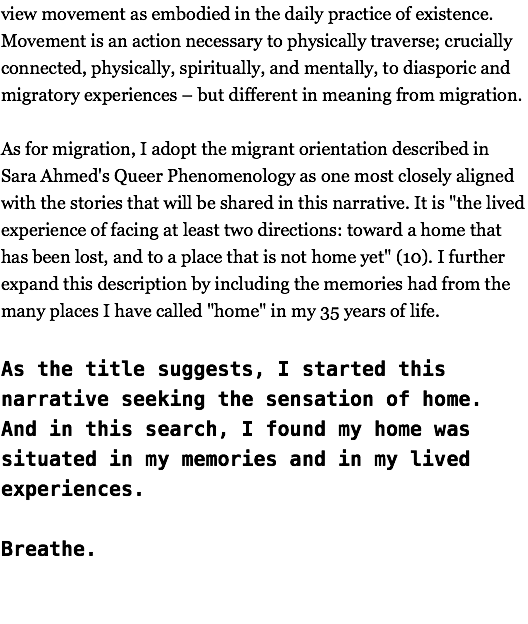

If I have to respond to the question, "where are you from?" then my answer would be that I am from Somalia. But I am a product of the diaspora. I am all at once a migrant and a refugee – my ancestral lineage and my lived experiences also making me a nomad.

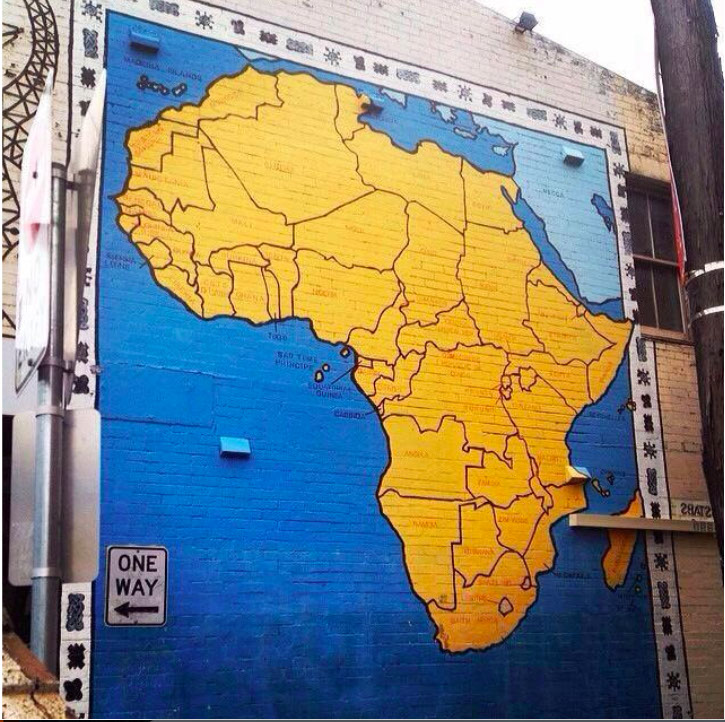

Defining myself as a member of the diaspora, I use Furusa, Little, and Vasquez's concept of Diaspora – a dynamic process; one that aims to explain the actions of people of "African, Asian, and Latin American descent who have been forcibly or voluntarily dispersed throughout the world" (1). The authors also accept the term's complexities – its cultural dynamism involving "substantive intercultural exchanges between peoples from different ethnic groups. It frequently requires the reconstitution or reconstruction of a culture and society by peoples uprooted from homes that borrow and adopt new cultural elements as the plaster to patch up the fissures in their cultural foundation" (3). I personally see these fissures in cultural foundations as an opening and opportunity for diasporic individuals to interpret and understand the world and its complexities through their lived experiences; one that does not reside solely in a particular culture, place, or space – but blends them in ways that enable for the existence of a diasporic orientation

In Cultural Identity and Diaspora, Stuart Hall further develops the

concept of diaspora and allows for some fluidity to exist around

diasporic identity production. Unlike the fissures aforementioned,

Hall explains that there are at least two different ways of thinking

about cultural identity and diaspora, and both are situated in the

post- and de-colonial experience. The first, Hall argues, can be

witnessed in the unity found in the imagined 'cultural identity," a

sense of oneness and connectivity to an overarching identity as

positioned by your identifying culture. According to Hall, this

'oneness' in our cultural identities is a reflection of the collective,

"the common historical experiences shared and cultural codes which provide us, as 'one people', with stable, unchanging and continuous frames of reference and meaning, beneath the shifting divisions and vicissitudes of our actual history" (223). In effect - and in connection to my work – this explains my identifying as black, woman, as pan-African, as Somali. Cultural codes and ways that exist as an expression and connection to a particular culture or way of being. Hall believes this conception of cultural collectivity has played a critical role in "all the post-colonial struggles which have so profoundly reshaped our world," and can be attributed to my ability to write this, or read this to you today (223).

Hall's other way of thinking about cultural identity is more directly connected to my diasporic experience. "Cultural identity, in this second sense, is a matter of 'becoming' as well as of 'being'. It belongs to the future as much as to the past. It is not something which already exists, transcending place, time, history and culture" (225).

Here, Hall speaks to the fissures mentioned by Furusa, Little, and

Vasquez; speaks to Powell's dis- and reappearance – speaks to the

many ghosts that haunt us from our past, and from the futures we

may or may not see or experience.

Now, I speak briefly to all those who belong to the diaspora – those who never had to leave their homeland to understand this queer orientation imposed on them by the same colonial constructs we still navigate today. I speak to these diasporic communities because my movements, migrations, and memories – my homes – are, and have been, situated in their lands; right here in Lansing, Michigan – and also in Canberra and Melbourne, Australia.

Furusa, Little, and Vasquez touch on this notion of displacement and diasporic difference specifically: "As we grapple with the complex dynamics of Diasporas, we avoid privileging migrations, whether they resulted from involuntary Diasporas or self-selective

migrations. Worldwide, colonialist and imperialist forces disrupted and dislocated indigenous peoples, economies and cultures and imposed their own governing assumptions as values in the lives of enslaved and colonized peoples" (2).

To all of you diasporic beings – on your land or away from it – I say mahadsanid. Waan is fahamnaa.

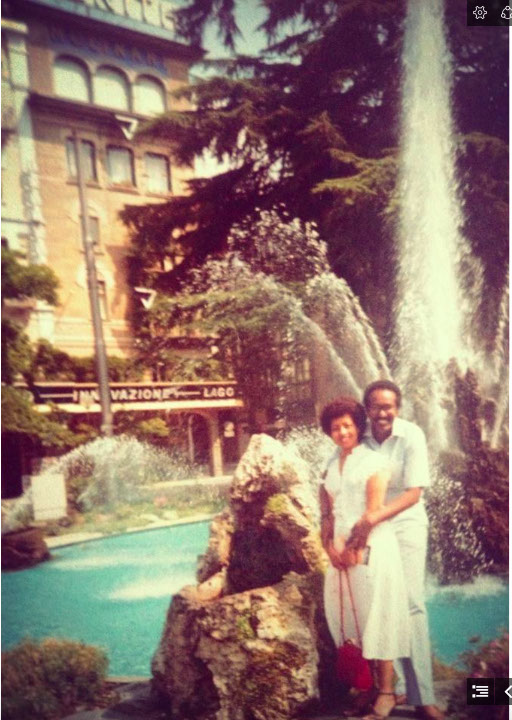

My father was born in Gaalkacyo, my mother in Muqdishu. She is of Yemeni/Eritrean descent, but her cultural claim is with the Somali people.

I do not have time to explain the complexities of her narrative,

politically and culturally, but I am addressing them for those who

may already know the nuances of her lived experience.

If you were Somali and asked me for my name, the answer would be different. My name is Suban Ahmed Mohamed Nur-Bile Koshin Ali Faarah Ismael Mohamud Saalah.

These names are my patriarchal lineage. And where the names end – as expressed to me – so does my known genealogy. Many of my cultural practices are based in story. Even our names are situated in story.

Thomas King points out in The Truth About Stories that the truth

about them is that they are all we are (62). We are all but made of

story. Some are ours; our experiences, memories, moments,

identities. And some of our stories are the stories of others.

I am not a metaphor.

Black as night, eyes like pools ...

I exist as you exist, immersed amongst other versions of me.

Tell me my story. Be the author of my world, and compare your

created world with others.

Do the similarities in your stories make it true?

A fuel for fusion.

Where do I fit when conversations about my story happen in your mind, or on patios far from my ears?

I am here. Ready to hear your version of my story.

.

Because I belong to the Somali diasporic community, I am obsessed with the telling of stories. Writing is just one of the many ways I enjoy doing so. Orality is also very important to me. I believe its practice relies more on trust, relationships, and memory.

You see, my country did not have an official written orthography

until October of 1972. Though attempts had been made earlier, John William Johnson's article, Orality, literacy, and Somali poetry explains: "In the decades before and after independence, the choice of an orthography for Somali was a volatile religious and political issue, rather than a mere academic problem of adopting or inventing a script suitable for this Cushitic language. Over twenty different writing systems, some Latin-based, some Arabic-based, and some based on scripts especially invented for Somali, were argued and debated over for twenty-five years before a government in Somalia finally felt powerful enough to implement one of them" (120).

The Latin-based Somali orthography adopted in 1972 was a decision of the Maxamad Siyad Barre regime; the same regime that would lead Somalia into its ongoing civil war. An important note made in this article – and much of what I aim to do in my future work – is Johnson's revelation that this decision to adopt an orthography had little impact on the practice and performance of oral poetry in Somalia.

Johnson discusses the theoretical arguments made in technological determinism; that the progression from orality to literacy (print and electronic based) has been connected to a progression in human mental ability (130).

Johnson, however, found for this to be untrue of the oral poetry practices of the Somali, arguing that literacy – written, oral, and electronic – are all tools of expression. But that here in the West, written literacy is privileged over orality, "giving literacy a power it does not inherently possess" (131).

In The Movement of Air, the Breath of Meaning: Aurality and Multimodal Composing, Cynthia L. Selfe argues that "our contemporary adherence to alphabetic-only composition constrains the semiotic efforts of individuals and groups who value multiple modalities of expression." Selfe then mentions scholars in rhetoric and composition – specifically mentioning Jacqueline Royster, Geneva Smitherman, Adam Banks, Scott Lyons, and Malea Powell – who have displayed the intrinsic value of other modes of literacy and ways of communicating ideas, reminding us that there is value to both/and; both the written and other ways of making meaning (visual, aural, oral, digital, etc.), academically or otherwise.

Selfe adds that these scholars remind us "in persuasive and powerful terms that people of color have historically deployed a wide range of written discourses in masterful and often powerfully oppositional ways while retaining a value on traditional oral discourses and practices" (625).

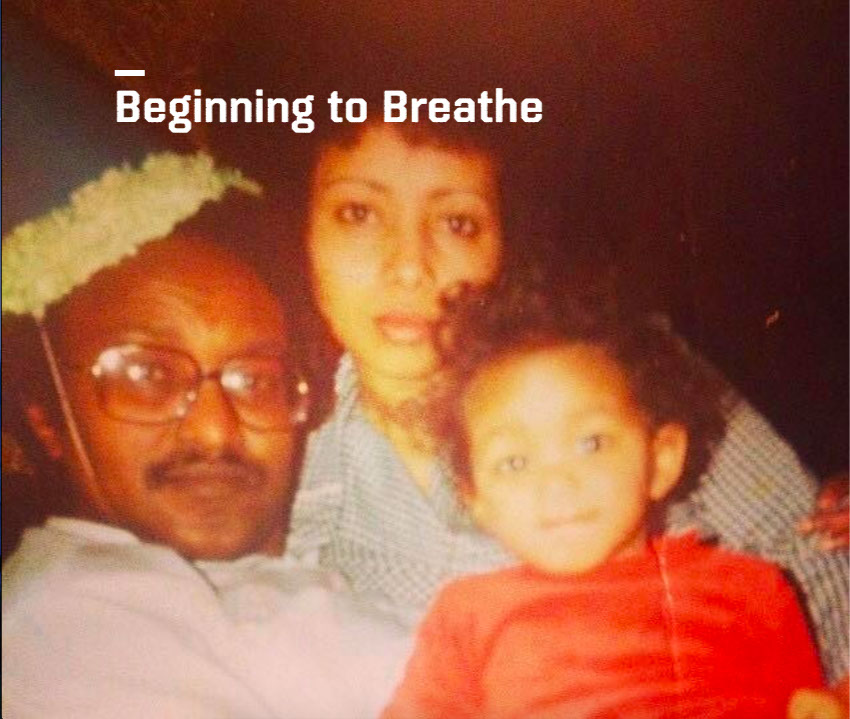

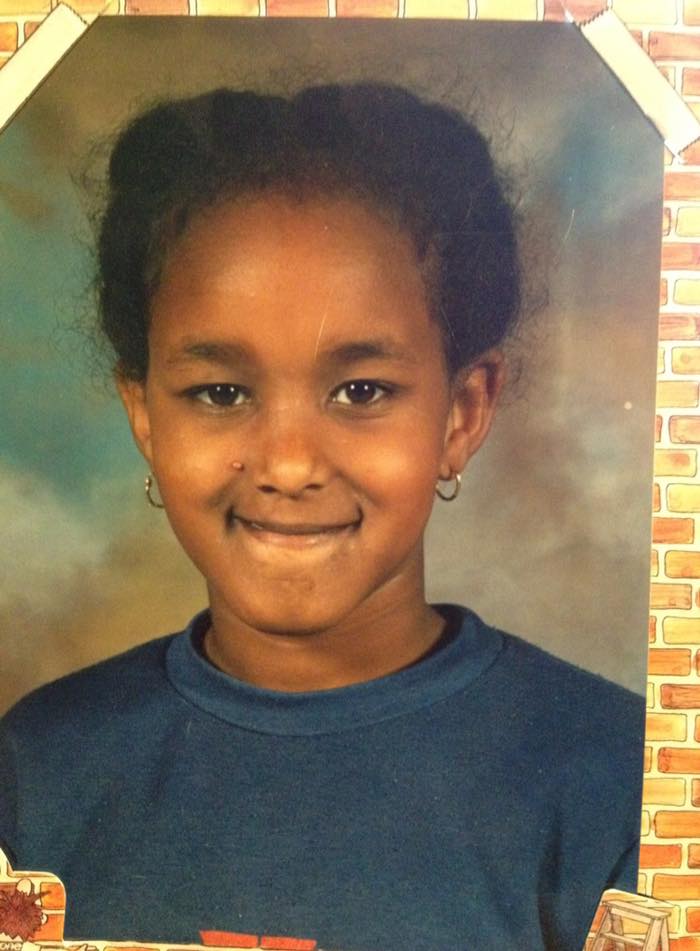

This story begins on the 18th of July, 1980, at 8:42 p.m. at Hôpital

Cantonal in Geneva, Switzerland. A Yemeni/Eritrean woman born

and raised in Somalia pushed her final push – and with the help of

forceps – her hefty-headed daughter slid into the doctor's arms.

The father, a tall, dark, mustachio-ed geel gire cut the umbilical cord and placed it lovingly in a bag where he would keep it for years to come; this physical embodied connection between two women he holds dear. He does that for all of his children. The ones that survive, anyway.

This is the fourth time Shahrazad and Ahmed have awaited the

arrival of a child. On this day, they rejoice because their child is

healthy, crying, alive. This child is me. I am the fourth born. The

second living daughter of the Nur family.

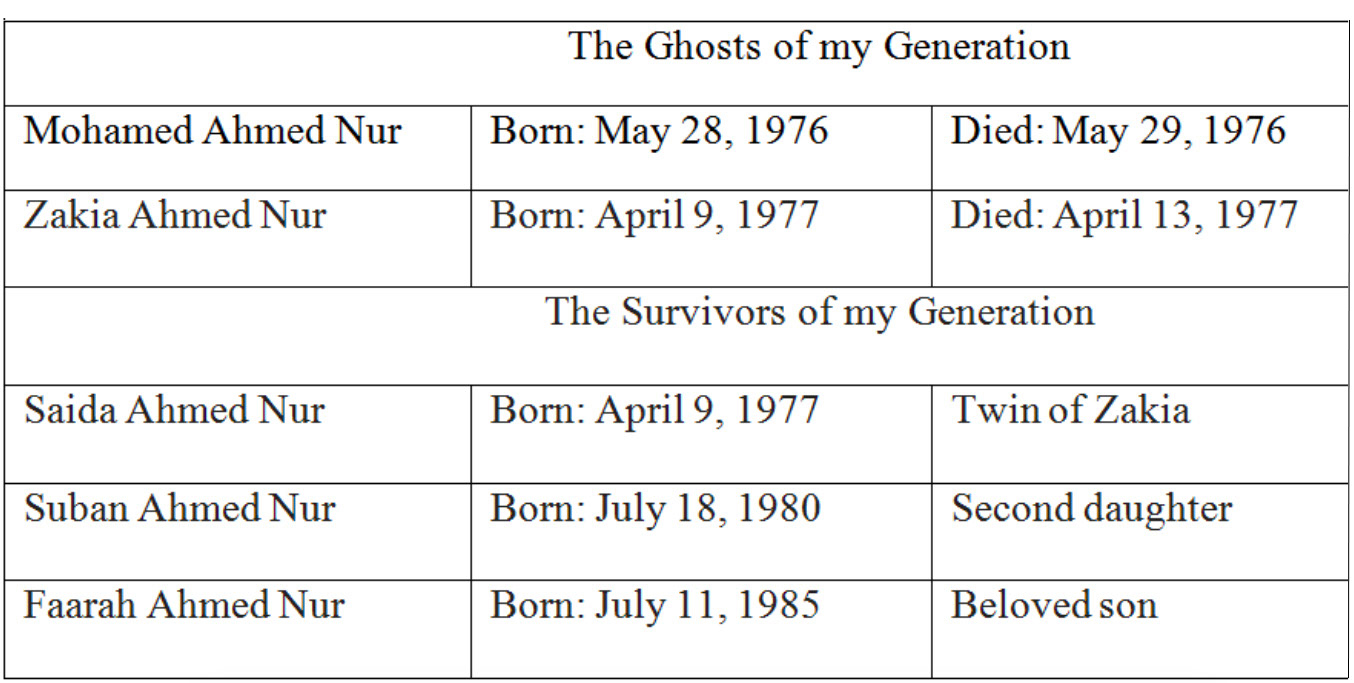

In the above table, I tell you a story. It is brief. I want to use Powell's tattoo again as an analogy for where meaning lies here. Powell talks about the visible line of the tattoo, and the space it denotes having meaning, "one an erasure of the other–the line an erasure of space, the space an affirmation of the line" (13). Here, the ghosts and the living coexist and make meaning in the same way. We, the survivors, are the line. And the ghosts of our siblings are the space, the affirmation of us, of our existence.

We are defined by our existence.

Being redefined, moment by moment, as new opportunities to be

become available.

I am becomes we are.

We give these connections a name: mother, father, brother, sister, wife, husband, lover, fiancé, friend, cousin, niece, daughter, son - the list goes on and on - 6.974 billion variations of relations.

We are, in essence, surrounded by strangers.

We linger in the lives of others; we are the strangers being passed on the way to somewhere, captured in the background of someone else's vacation photos, waiting behind someone in a checkout line.

We linger ... fortunate to find commonality amongst the ones we

know, the ones who help define our existence.

Ones like you.

Connecting and disconnecting

Getting engaged and disengaged.

You, give me a different smile.

You, get to pull my hair back from my face and tell me when I have spinach in my teeth.

You, get to walk with me places, be in my photos and wait in

checkout lines with me.

You get to watch me cry, make me cry.

You get to hurt me if you choose to. And sometimes, you will.

But only because we are connected.

We are fortunate enough to linger here together

I feel the need to talk to you about my feelings towards Switzerland

because it is where I came into literal existence – and yet, I have no

ties to this place or space. I think of this country and I make no

claims. I have soft, almost forgotten memories of Lac Leman,

laughter, and life-sized candy canes. This place is not a part of my

heritage, but it is a part of my history. I began to breathe here. It’s also a place in my past I don’t bring up often. It is the surprise element in my 'home' narrative. A perfect way to deflect the, “I see. But – where were you born?”questions I sometimes get when my skin color and colloquialisms

don’t make sense to others. It doesn’t help them to know I was born

in Geneva, it just confuses them. Being born in Geneva (while also

being Somali with an Australian accent in the Midwest) is

nonsensical. This place is only a part of me in that it is a place where

I spent my first four years of life. My feelings about Switzerland are

as neutral as the country is stereotypically known to be. Though I was born there, I am not granted citizenship.

In Switzerland, I was nothing but the child of a U.N. economist. Like

an army brat, I was a U.N. brat – born into the transience that

foreshadowed my journey and embodied my nomadic genes.

I write this migration story because it is not something I can ignore.

As Edwidge Danticat explains in Create Dangerously, it is impossible for a nomad or immigrant to not have travel and movement on the mind, "just as the grief-stricken must inevitably ponder death" (16). As a Somali woman, it is part of my narrative to be thinking about travel, movement, and my memory of it.

Sheeko sheeko.

Sheeko xariir.

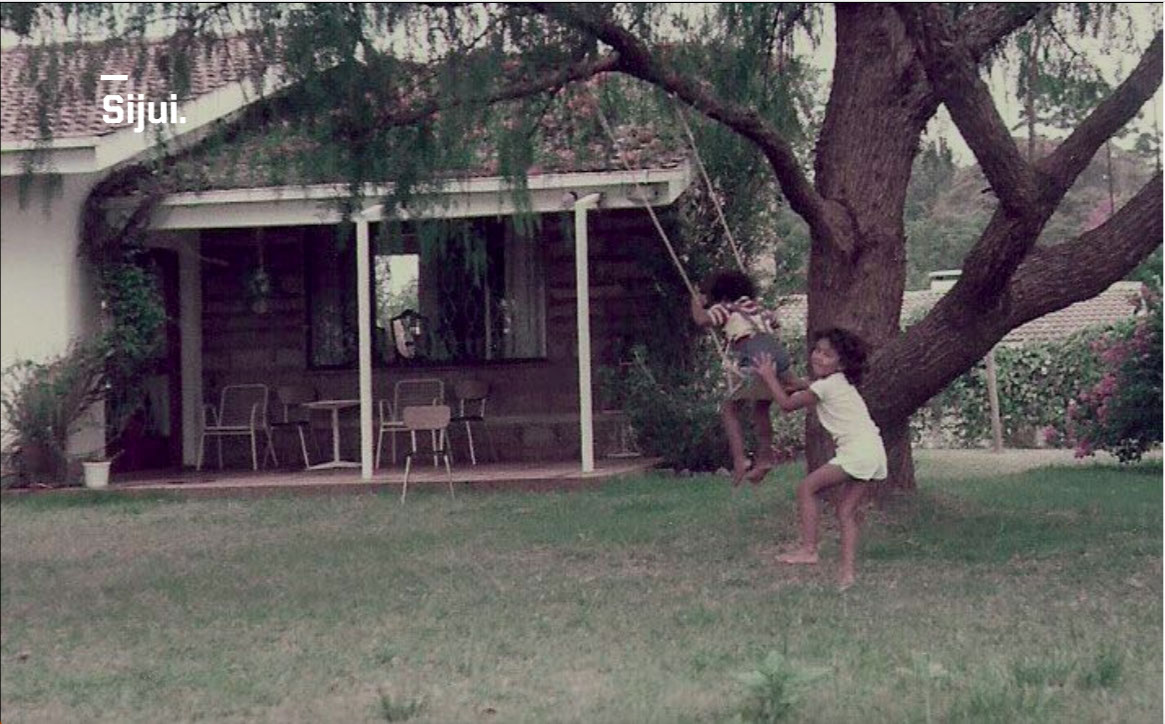

At age five, my father took a different U.N. job that moved my family to Kenya. A neighboring country to Somalia and in much closer proximity to our large extended family. Though my memories here are opaque and hard to grasp, the feelings they generate are ubiquitous in my body. I want to speak more directly here about my orientation to my nostalgia as an object of my imaginary. Ahmed explains what orientation denotes to her philosophically. "Orientations are about how we begin; we how proceed from "here," which affects how what is "there" appears, how it presents itself … orientations, then, are about the intimacy of bodies and their dwelling places" (8). Ahmed also discusses finding out about our orientations through disorienting experiences. By experiencing the unfamiliar – whether by getting lost, or via migration – I am made aware of what I orient my body (internal and external) with. My orientation to Kenya, then, is alive in my memory.

This place still feels like home in my memory. I made my first friendships there.

The German girl next door that taught me how to sunbathe like a movie star on deck chairs in our backyard.

My aunt who tried to explain why we didn't do that, but it didn't make sense yet.

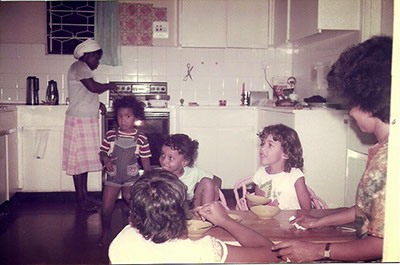

The daughter of Grace (our live-in cook) who played for hours with me in the garage, braiding my hair and playing with Barbie dolls.

Gigi – Abdi Steakhouse's daughter – whose family was also famed for being related to Faarah; a character in the film, Out of Africa.The Indian girl at Braeburn Primary School who stole my gold necklace and inspired me to slather my hair in Vaseline to replicate her straight hair.

Kenya was where I learned to speak English. It was also where I learned to begin feeling uncomfortable in my own skin, throug racism and colorism. On the one hand, I learned I was black and that this was something bad – but on the other hand, I also learned I was Somali' black, which came with its colorism privileges.

Racism and colorism are steeped in this colonially constructed knowledge Anzaldua speaks of in Borderlands – the knowledge that to acknowledge darkness as something sinister, we must first turn lightness into something positive. And as such, with this duality of light and dark now in existence, we can now ensure "Darkness, my night, is identified with the negative, base and evil forces … and all these are identified with dark skinned people" (Anzaldua, 71). Colonization has created human hierarchy through the tones of our skin. The darker you are – the darker your darkness. The more sinister, the less worthy you are.

I returned to Kenya as an adult last year and stayed with family friends who lived near my old neighborhood. Though I didn't get to see my old house, I got to see my old school. Just being in Kenya gave me a strong sense of nostalgia. I'd almost forgotten about the landscape: so green it hurt your eyes, and the loud and glaring matatus on the road. My love for Kenya returned instantaneously upon receiving its moist air in my lungs.

There is also the skin of the social that Ahmed warns we must navigate – its borders; affected by the "comings and goings of different bodies, creating new lines and textures in the ways in which things are arranged." When I asked you all to stand earlier, I was connecting you with the skin of the social, and the ways that things can change, even in the same space, due to the movement of others (9).

The following night, we went to Havana Bar in Nairobi to celebrate my return to Kenya since childhood. A group of us. Four Somali women. Catching up and grabbing a drink at a bar. As we sat there enjoying our beverages we heard glasses break behind us and a man yelling at the bartender. My one friend facing the scene stood up immediately to ask for the man to be escorted out.

"I shouldn't leave," he screamed. "You are the ones who need to leave, you fucking terrorists. You are killing our people and ruining our country!"

This man was already drunk, violent, and angry – but he directed his anger towards us in the end. And as he yelled for us to go home, we just stood there – some of us fighting him with our words, the rest of us fighting off tears.

In Joanna Pfaff-Czarnecka's article From 'Identity' to 'Belonging' in Social Research: Plurality, Social Boundaries, and the Politics of the Self, Pfaff-Czarnecka uses a horrific case in Dresden, Germany, where Alex Wiens, a right-wing extremist of Russian-German origin attacked and killed Marwa al-Shirbini, a "33-year old academician of Egyptian origin." Before killing her, he asked her what she was doing in Germany, and didn't understand why and how she could feel at home there due to her Muslim background. In essence, "Alex Wiens couldn't imagine feeling at home in Germany as long as Marwa felt

comfortable there. Belonging is thus the object of continuous negotiations between individuals and collectivities" (200).

The social skin of Kenya has changed since I was a child. What we, as a group of diasporic Somali women had done at Havana Bar disrupted the notion of belonging in this Kenyan man's homeland, causing him to become tense and threatening because the current

narrative links Somali with terrorism. His reaction was not in tandem with the fact that our physical presence was accepted by the collective. We lost our negotiation with the

individual, but not with the collective. It's an awful feeling knowing you are hated for reasons you have no control over. A feeling I'd been used to in the West, but shocked to

know I'd feel that way in Africa, too. I can't breathe.

Sandy streets, the smell of smoked goat's milk and gasoline, and Iftah Ya Simsim* on TV … these are memories from my six months living in Muqdishu. I am seven. Muqdishu is a place where you could feel the sun permeate through the walls at the break of daylight, like the insects that worked their way into your skin if you played outside too long.

No one needed a watch there. The longing sound of the adhan* silenced the streets, redirecting everyone with new found purpose – serving as a reminder of our mortality, five times a day.

Broken green glass glistened atop the high white stone walls, protecting our home from the dangers of the world outside our gates. Beyond the white walls, we played gariir and kuu kuun with the neighbor children. The occasional goat would disrupt someone’s hiding place and we’d laugh watching them run circles around the bleating, bloated animal. We’d reward ourselves with a day of play by running to the corner to buy ice cream; tin cups full of milk and sugar, frozen into little cylinders of quenching sweetness.

My mother’s sister lived around the corner, and my younger cousin Edebo was a constant source of annoyance. Her father would return from his travels with chocolates and Barbie dolls, and anything else she’d ask for. An only child, she was spoiled and sulky for a good hour before she’d warm up and play with the rest of us. I didn’t know at the time, she was compensating. Her father, a military general in Siad Barre’s regime, would be known for his violence and anger.

I paid little attention to the adult dynamics around us. Things were tense and people were anxious, so the farther you could stay away from conversations being had in the kitchen or the living room, the better. We knew things were bad, we just had no idea how bad. War was just a word at this point.

And then one day I watched my mother hug her sisters the way she hugged people at funerals; their shoulders drenched in tears. We were leaving. For good this time … to a strange place called Australia.

I like to tell people I was seven when I moved to Australia, when I

was really eight at the time. I don't know why, but eight just feels so

grown, like I should remember more than I actually do.

I do, however, remember the first time I saw a vending machine. I

blame the Archie comics we read in Muqdishu, riddled with Mars,

M&Ms, and Skittles commercials. And though I was born in

Switzerland, I remember wondering what these candies tasted like.

You never saw Lindt ads on the back of Archie* comics so they had

no appeal to me at that age. Plus, good chocolate was plentiful in

Geneva. Who’d even think about M&Ms there? But those comics in

Muqdishu had me yearning to taste American chocolate. And there

they were, taunting me behind that glass pane at the airport on my

first day in Australia. My life there was much like that damn vending

machine. There was candy everywhere, but you had to have the coins

to access what it was you desired.

We moved to Deakin, Canberra. A posh part of the capital of

Australia. We lived in a set of flats across the road from the local

shops. It was the first time I saw Nosferatu's face on a television

screen.

Funny thing about places where horror isn't experienced by everyone

– it is watched on television and made up – it's like humans need

this horror to function.

Where there are no stories of horror, the stories are invented.

There we were fleeing to safety from an impending civil war in

Somalia, cooped up in a flat where an eight-year-old wakes up to

Nosferatu on television.

I want to call my mother and ask how many bedrooms we had in that

place, but she probably doesn't remember much either. She was 35.

The age I am today.

We stayed on that side of Canberra, finally moving across the

highway to Curtin. Short of having to share part of the backyard with

the next door neighbors, our house on McCormack Street was

dreamy in the way that one envisions the quintessential home

acquired when pursuing the American dream, for example. It had a

large stone fireplace (which isn't something you ever use in Australia,

but still), high ceilings and a guesthouse attached to the kitchen. If

the house had a color aura it would be green, all sunlight and trees.

McCormack Street was shaped like a horseshoe, and our house was

almost right at the center of it. I really loved that house. Curtin as a

suburb, I was indifferent to. Probably because I remember it as the

place where I learned what racism was. School was hard back then,

when it wasn't just kids you had to watch out for.

My teacher, Mrs. McArthur would single me out every week in some

manner, and humiliate me in front of the class. And though that was

hard, the worst part was having Virginia – a girl in my class – accuse

me of stealing her 8-color ballpoint pen and having that rumor

follow me into high school. Her mother had Multiple Sclerosis, if I

remember correctly. Virginia was hurting and just needed someone

to be angry with, and that person happened to be me. I guess that's

when I learned people are going to think what they want about you;

tell the stories that they want about you. I remind you of the words of

King again, "The truth about stories is that that's all we are."

Luckily, I changed schools and repeated fourth grade; I was put with

children the same age as me. Changing schools was partially to do

with our move to Hughes (back on the other side of the highway

again), but a lot more to do with the fact that my parents could now

tell that Mrs. McArthur was racist.

Hughes will always remain an ethereal place in my mind. The house

on Kitchener, though less idyllically situated than McCormack, is

what I recall when I think of home in the way you think of home

when you watch The Wonder Years: dreamy, of another time, and

constantly awash with a subdued golden hue. And in Hughes, there

was also Carroll Street: A place where all the international students

and other immigrants lived. We spent a lot of time there, and I had

no problems with the teachers at Hughes Primary School when I got

there. Hughes was a good fit.

It wasn’t until my first year at Alfred Deakin High School when my

friend Jill brought up the pen thing again. The conversation was

quick and awkward, at the end of the long hallway near our math

classes. I can't remember where I saw her, but Jill was quick to point

out her surprise in being in the same year.

"I remember you! You were in Mrs. McArthur's class, but you were in

year four, right? You stole Virginia's pen," she said.

I still cringe to this day. I recall asking my mother for that fabulous

8-point pen and owning one around the same time that Virginia

likely misplaced hers. If we're going by evidence, I suppose it looked

pretty damn bad. But that pen was mine, and I doubt I'd have had to

work so hard to prove it if I weren't the black immigrant kid of the class. I couldn't breathe.

Here, I remind you of Powell's meanings delineated by dis- and re-

appearance. To me, this pen story from my childhood was a ghost,

and yet, it reappeared in my narrative many years later.

-crop-u940.jpg)

1 - 4

<

>

I was a pretty good child, so my parents didn't get many reports.

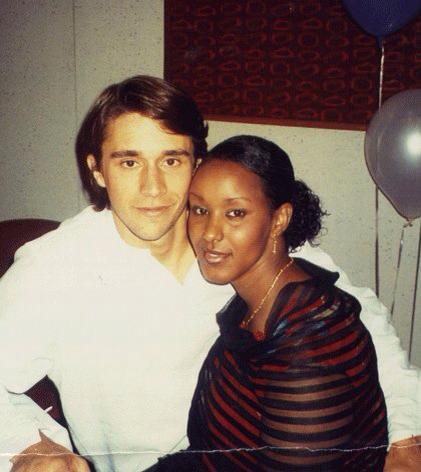

Then one day, I told them I was in love with a young, white American

man. Then four years later, this young white American man called

my father to ask for my hand in marriage after he had proposed to

me and I had said yes. I watched his face, awkward on the phone.

"Hi, Ahmed. I'm doing great. Yeah. Oh great. I just wanted to say …

and it would be an honor if you would bless our being married."

He looked over to me, cupped the base of the phone and whispered,

"He's noooot saying anything."

I am daddy's little girl. That call would have been hard for anyone to

make. But there I was, this 24-year-old woman, knowing I had

picked a partner that was everything they hadn’t expected. And

knowing full well I planned to move.

"Every increment of consciousness, every step forward is a travesia, a

crossing. I am again an alien in new territory. And again, and again.

But if I escape conscious awareness, escape "knowing," I won't be

moving. Knowledge makes me more aware, because it makes me

more conscious. "Knowing" is painful because after "it" happens I

can't stay in the same place and be comfortable. I am no longer the

same person I was before." (Anzaldua, 70)

It was January 6, 2006. My sister (who to this day begrudges me for

leaving) bought me a one-way ticket to Lansing, Michigan. It was my

wedding present. I flew Hawaiian Airlines via Honolulu. Having

gone through immigration via LAX, I expected my K-1 visa experience to be a nuisance. But the people I encountered working in immigration in Hawaii were happy and pleasant. It was a breeze. They

welcomed me to the United States and congratulated me on my

upcoming wedding. This was the first time I was migrating by choice

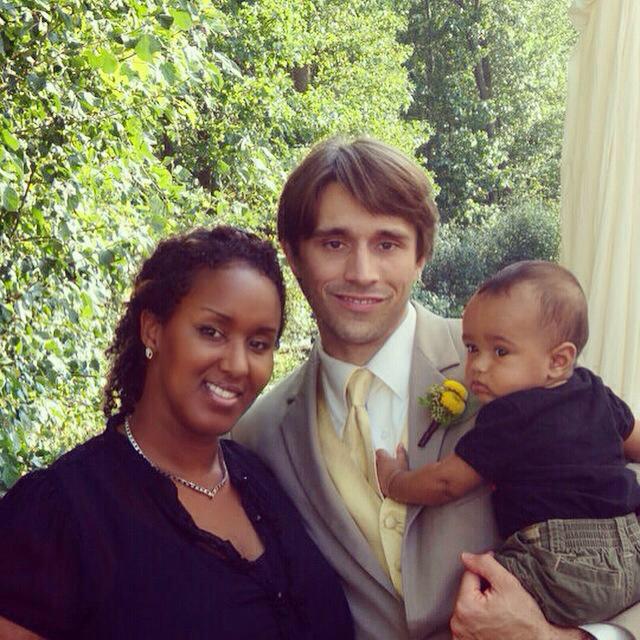

I am became we are. We bought a house in 2008. We had a child in

2010. Just as my idea of home was shifting, so was my idea of family.

My life in Lansing is not a memory; as I write this, it is my now –

affirmed in the lines – the space an affirmation of what I am no

longer around; The space in my heart affirmed by the lines of my li

I have made great lifelong friends, have had great jobs and have

volunteered and engaged heavily with the community of Lansing. I

did everything to get connected here. To feel rooted here. And

though I am in my tenth year living in Lansing, this place is just

starting to feel like home.

1 - 5

<

>

Hidalgo | Chambers | Hutchinson | Shade-Johnson | Brentnell | Leger | Braude | Sweo | Nur Cooley

___________________________________

Published by Intermezzo, 2018