Woman in Relation:

On Sisterhood, Self, and Marriage

From left to right:

Me with my sisters Thea and Talia

—

by Naomi Sweo

This is the story of a storied woman.

I believe research is a lived process (Kirsch and Rohan). My research interests cannot be separated from who I am as a person, or who I was, or what my experiences have been. In her research presentation "Techne, Rhizomes, and the Authored Self," Jacqueline Rhodes asked, "How does lived experience work towards systemic critique?" How do our lives contribute to our research? How can our stories work to dismantle unequal patriarchal power structures? I am an unmarried woman who has qualms with the institution of marriage, and yet the topic fascinates me and guides my research. Why? How can I critique the institution of marriage from outside of it? Why does it often consume my thoughts? And in answer, as Rhodes said, "The gap between knowing and the desire to know is all we have." The institution of marriage affects all of us, top-down, if the people around us are marrying and divorcing. Even if (like me) we aren’t married. Research is one path to take towards understanding.

Writing is not a reflection of knowledge, but a creation of it (Estrem). I write to understand, to grasp some of the thoughts flying around in my head like scraps of paper in a wind tunnel, to read the slip of paper closely, to touch it, to make it real.

______

"The gap between knowing and the desire to know is all we have."

(Rhodes)

In this piece, I trace back my enthusiastic academic obsession with marriage to its rhizomatic beginnings; to my parents' divorce, to being raised as a girl with outspoken sisters in a Christian household in a Christian country, to the instability that comes with being raised as an American nomad, to finding intellectual community in the digital world. All of these parts are visible in pieces in the purposeful multimodality throughout—my attempt at visibly rendering life. I initially attempted to create a research narrative based on my family members' gender performances, to understand how my learned and made femininity related to the instruction passed down to me by my older sisters and mother. Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity and Gayle Salamon’s Assuming a Body: Transgender and Rhetorics of Materiality gave me words to understand and articulate the ways that gender performances had become a part of my identity, whether I wanted them to or not. I use Judith Butler's phrase “gender performance” (Gender Trouble 187) to mean those actions and rituals we repeatedly do that add up to an overall impression of “gender,” however inconsistent across individuals. But more so than general issues of gender or femininity, the topic of marriage kept butting its way in, as it is wont to do in my family.

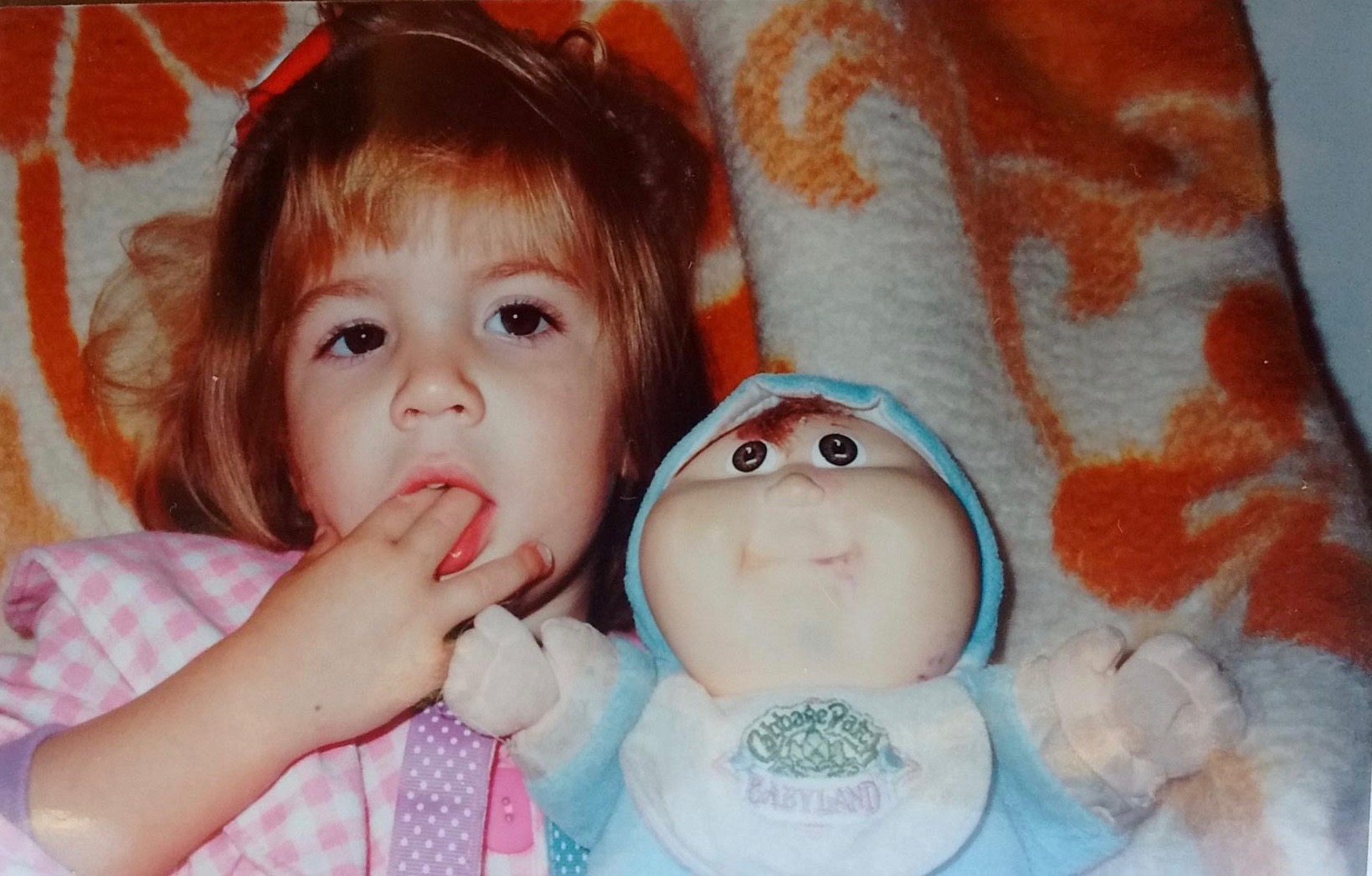

The past is an incomplete archive that is constantly reshaped by remembrance. This piece is a mixture of memoir, in which I draw upon my own memory, and feminist theory, in which I draw upon the memories and musings of the feminists, rhetors, and memoirists who came before me. Peppered throughout are family photos provided by my mother, who took photos of photos and emailed them to me from her phone—a feat, if you know my mother, and an even more impressive one because she accomplished this with very little visible flash. Some media used within are videos—some screen captures and others interviews—I completed with my mother and my two sisters, Thea and Talia, in December of 2015. I kidnapped my mother and Thea separately for several hours before their flight back to California after visiting me in Lansing, Michigan, where I am attending graduate school. I pointed the camera of my MacBook Pro at them and asked them to tell me about our lives, which they kindly did, and then they pretended to be unfazed by the narrative that came out of it. I interviewed Talia several days later over Skype.

I am a woman only in relation to the other women who have come before me and raised me, either as my family members or my intellectual forebears who I have met mostly through the melding of minds. I thank them all, as this piece would not look or sound or read the way it does without them.

***

I moved to Portland, Oregon, from Granada Hills, California, where I’m from, when I was twenty-two. A few months later, I was sitting cross-legged in Laurelhurst Park, learning to meditate with a group of people I’d never met. We sat in a circle on the patchy grass as a bearded, tattooed man advised us to gently lower our eyelids.

“Count your breaths, in and out,” he said soothingly. “In: five, four, three, two, one. Hold it. Hold it. Hold iiit. Aaand out: two, three, four, five.”

I looked around at the other members of the group and closed my eyes. “If you have any thoughts, it’s okay,” he instructed. “The purpose is not to omit all thoughts, because it’s not possible to. I find it helpful, if I have a thought, to imagine writing it on a little slip of paper. Then crumple the thought-paper into a little ball, and set it in a river. Let it float away down the river, for when you’re not meditating. You can come back to that thought after. For now, just look at the slip of paper, read it, and imagine it floating away to be dealt with at another time. Breathe through it.”

Laurelhurst Park is full of trees taller than buildings, much taller than my seated form, with winding walking paths. I could hear people passing by us, talking. I mind-wrote it on a slip of paper. What are they thinking about us? They probably think we’re fuckin’ weird, granola, artsy super-Portland people. They think we’re hippies. I could feel their eyes on my back. I could feel their eyes on the hairs on the back of my neck. I could feel their eyes in my head. I couldn’t put it in the river. After five minutes, the phone timer went off and we all discussed what we learned from the experience, what meditating was like for us. Most of us had never done it before.

I started to talk, without thinking this time. “I was noticing everyone walking around us, the talking. I was wondering what they were thinking about us. But I realized that it’s not the people passing by whose voices I heard in my head. They were my sisters, Thea and Talia, and my mom. I imagined them judging me, all the way up here.” The other people in the group nodded.

Me, Talia

My oldest sister, Thea, was twenty-one when she got married to her high school boyfriend. My oldest brother, Casey, was nineteen when he married his now-wife. My dad was nineteen when he married my mom. Talia was a virgin until she met her now-husband. The longest relationship I’d been in lasted a year and a half and ended when I told him I wanted to move to Portland and he didn’t want to come with me. I went through a phase of not wanting children, considering whether or not I was queer or polyamorous, sleeping around. I had to get away from home and figure out what I wanted and what I believed without the voices of my sisters and my mom in my head, pulling on my neuron-strings, whispering, Marriage (lifelong). Babies (an even number, four). Sex (after marriage).

My mom's mind-voice is especially loud. Many days, say, before traveling in Europe alone or just going to class, she would remind me to not walk in alleyways or parking lots, to be vigilant at all times, because some girl somewhere far away had gotten raped yesterday walking from class to her car. It's become a familiar familial refrain. I'll pull on my jacket as I walk out the door and say, "Going to the movies! See you all in a few hours!" Thea or Talia will jump in, smirking in the direction of my mom, "Be careful of rapists! Don't walk anywhere that isn't well-lit!" Constant sexual vigilance was my birthright.

My mom emigrated from Communist Romania when she was nineteen. I wonder if the emigration is a part of all of us now, along with the sexual-violence paranoia, renewing over and over in us each time we move. My oldest brother, Casey, lives in Abu Dhabi now, Talia in Santa Barbara, me in Michigan. Thea is the only one that stayed in our hometown—well, one of the many almost-hometowns. Home is wherever my mom is, an ever-moving mark, yet I'm rarely there.

The life of an academic should be well-suited to me, as it generally requires moving, an experience I'm more than acquainted with by this point. My experience mirrors what Ashley J. Holmes writes in "The Essence of the Path: A Traveler's Tale of Finding Place": "My reflections on the past draw a connection between my initial sense of placelessness and my developing desire to discover a new home." This feeling of placelessness that I've felt since moving to California from Tennessee when I was seven has never left, and I'd like it to. As a graduate student, having a "home" is still far off.

Gloria Anzaldúa writes in Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza that knowing is moving, that one who learns something new is no longer the same person, and can no longer be in the same place.

They inhabit a new plane. "'Knowing’ is painful," she writes, "Because after ‘it’ happens I can’t stay in the same place and be comfortable. I am no longer the same person I was before” (Anzaldua 70). I live in her nepantla, an in-between space, a severe loss of life control and the ensuing rush of anxiety.

_____

"'Knowing’ is painful because after ‘it’ happens I can’t stay in the same place and be comfortable. I am no longer the same person I was before."

(Anzaldúa 70)

When my understanding of life changed, so did my surroundings. Moving to Portland was a sort of reminder that I was a storied individual, but changeable.

In "Narrative Analysis: A Feminist Approach," by Roberta G. Sands, she differentiates between the narrated self and the narrating self, or the self constructed in the narrative and the self that does the telling (qtd. in Sands 62). As part of a postmodern feminist methodology, this sort of narrative analysis can be applied to research participants. In the case of an academic memoir, I am applying narrative analysis to my own story. I am both the narrator and narrated. In my application essay to Michigan State University's graduate program in the Department of Writing, Rhetoric, and American Cultures, where I am now a student, I write, "After a lifetime of reading novels, of quiet epiphanies and overlooked papercuts, I cannot help but to occasionally imagine myself the heroine of one." Our life is a story we create over and over.

Moving can feel like a new chapter. Moving to Portland wasn't my first big move. Or the third. Or the fifth. My mom moved me and my sisters and brother to California from Tennessee when I was seven. My parents had just gotten divorced after being separated for two years. Marriage always fascinated me due to its felt absence from my life. I only have one memory of my parents together. My memories associated with marriage are conduits of my mother's pain at their divorce.

I lived all over Southern California before I graduated high school, moving every three years or so when my mom felt like a change. I can't sit still for long, in life or in a relationship. I'm used to moving on when something feels lukewarm, on to the next place to be learned and known.

From front to back: Thea, Talia, me

My sisters and I had a ritual each summer when we would visit my dad in Tennessee for a month. Dad would drive us to the big bookstore in Chattanooga and let us roam for hours. I’d read the back cover of every new fantasy YA novel, the first few pages, a full chapter if I liked it. Other shoppers would mill around me, trying to peek at the books behind my back, but I didn’t notice or care. My favorite books were adventure stories with a young female protagonist. My favorite was the His Dark Materials series by Philip Pullman, in which the young main character Lyra leaves her world to travel in another, and eventually helps lead an uprising against God. While my body was in my bed in suburbia, my mind was far elsewhere.

Over time at the book store, I’d make my way over to the wedding magazine aisle. The Knot, Martha Stewart Weddings, pink and spring green and looping white calligraphy and pages upon pages of dresses. Always a smile on the cover. The dad walking the bride down the aisle. Both parents’ names on the invitations. I could never quite find what I wanted, so I’d pull out my lined notebook paper and draw a picture of the dress with little penciled arrows that pointed to specific details. A ruffle here, cap sleeves. On top: fall wedding. Colors: orange, brown, red, green. Yellow velvet shawl. Place cards set on pumpkins and squash. I’d rip out magazine clippings of dresses and rings and cakes I liked, but it would rarely be exactly what I’d imagine. One summer I picked out a wooden box at Michael’s. I wood-glued filigree to the top and screwed on ornate gold clasps. I stained it a warm chestnut color. I put all my magazine clippings and drawings into it, filled it to the brim. I’d get home from school and thumb through the pictures, add a few more from my new subscriptions. Fantasy Me went on adventures in other worlds. Real-Life-but-Imagined Future Me would marry in the fall, when the leaves were changing.

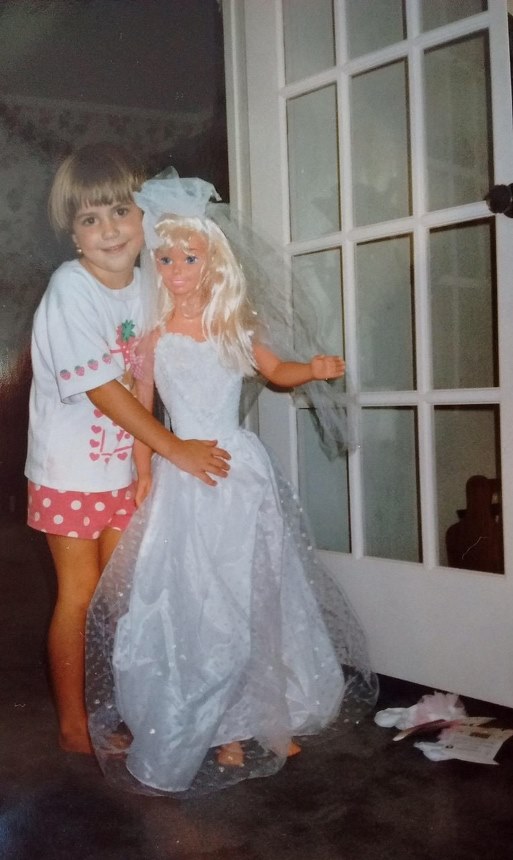

Me with My Size Bride Barbie

After watching The Wedding Planner over and over during the summer, I wrote in my journal that I wanted to be a wedding planner when I grew up. This was just after I grew out of wanting to be a supermodel, a future occupation I had chosen simply because my oldest sister, Thea, told me that's what I should want to be. I didn’t quite know who Cindy Crawford was, but I did know that I would love to be my Barbie made flesh.

That wedding box doesn’t exist anymore. Or, I suppose it’s sitting in a trash heap somewhere in Southern California decaying very slowly. After years of not looking through it, I looked through it one last time when I moved to Portland to make a life for myself that wasn’t based on the opinions of others. For some, home means safety and security. For others, as Jacqueline Rhodes said, "Home can wound and stagnate us."

_____

"Home can wound and stagnate us."

(Rhodes)

Nothing was my taste in my wedding box anymore the last time I went through it. The clasp on the box I had stained one summer in my dad’s backyard in Tennessee was broken. I threw out the box and the clippings inside. Wedding blogs gave me a quicker fix than my monthly magazine subscriptions when I needed to calm down. Pinterest allowed me to take pictures from the different blogs I liked and put them in a digital mood board. It allowed me to collage my ideal future, to feel the creative sensation that creating and adding to the wedding box had given me. but quicker, like a syringe straight to the vein. A few weeks before I graduated from undergrad in 2011, I had my first panic attack. I scrolled through my secret Pinterest board labeled “Wedding” until I stopped hyperventilating. I fetishized marriage, treating it as the answer to my life's instability. Staring in the face of a major life upset, falling back on the idea of a stable, traditional, pretty life calmed me. Nepantla. Academia lends itself to anxiety and placelessness more so than to a sense of home and stability.

In "Super Mom in a Box," Lindsey Harding writes about the experience of being a Pinterest user. Spending hours on the site imagining a happy life with perfectly crafted birthday parties served as an illusion of productivity, an escape from the tedium of her real experience of being a wife and mother. Her "interactions with Pinterest pulled [her] into 'the omnipresence of postfeminist identity paradigms' and defined [her] according to hyperdomestic, hyperfeminine, and hypermaternal responsibilities." This safe haven of imagined happy domesticity allowed her to feel like a happy housewife without actually being one, effectively trapping her within a virtual domestic sphere. Pinterest's "conditions enable[d] meaning to be abstracted into a simplified representation that precludes messy, uncomfortable contradictions." Pinterest allows its users to live in a story, to pin and pin and pin as a way of feeling productive, while really spinning in the hamster wheel. It's a digital narcotic.

My mom became a Christian when she was in her thirties, and she went full Christian. Her particular denomination is called Charismatic. How apropos. She started believing in tongues, demons, especially virginity, and generally controlling every aspect of her daughters’ lives. Until I started going to a public high school, I thought I was going to be a virgin until I married. Marriage was always the goal. Dating wasn’t allowed.

Gloria Anzaldua writes, “The Catholic and Protestant religions encourage fear and distrust of life and of the body; they encourage a split between the body and the spirit and totally ignore the soul; they encourage us to kill off parts of ourselves” (Anzaldúa 59). In Borderlands, Anzaldua writes of the knowing, the understanding of the connection between mind, soul, and body. This false ternary plagued her in her early days, as it did me. Instead, the mind/spirit/body should be understood as a trichotomy. In accepting one's "animal body" and "animal soul" along with the "mind" (Anzaldúa 48), they can begin to feel more complete.

So I got my first boyfriend and my first thong. The boyfriend was sixteen and the thong had a little plastic heart attached to the G- string. As far as my mother knew, I was with my best girl friend every weekend at the mall movie theater. My mom called once and asked to speak to her.

“She’s . . . in the bathroom,” I said.

“I’ll wait."

My mother must have heard rustling on the other end. I thought about changing my tone of voice, saying my friend didn’t want to talk to her, saying my friend was throwing up in the bathroom, saying there was a bomb threat and EVERYONE HAD TO LEAVE NOW!

“Is Colin there?” my mom asked.

“Yes,” I admitted.

“I’m coming to pick you up," she said.

I was working at an educational publishing company in Los Angeles when I first found A Practical Wedding, a website "working to build a cultural conversation about what it means to be young(ish) and married right now, in this cultural moment, [and] working to collectively build a positive egalitarian idea of what marriage can be in society, and what it can mean in our lives" ("About APW"). It was four months post-panic attack.

The front showroom at my company was floor-to-ceiling glass. The cubicles in the back had no windows and no ventilation. I drove three hours each day on the 405 freeway to sit in an office chair from the ‘60s with a perpetual stain in the grey? brown? tweed underneath my ass. Everything smelled like dust. I imagined there was a thick layer of dust settled at the bottom of my lungs. I sneezed periodically as I copyedited sanitized history textbooks. I was dating a boy I hoped to marry. We had issues. I could see through to the end of my life, I could see the shape of it, the muted colors. All I knew was my family’s and church’s approaches to marriage. All I’d ever wanted was to get married. All I ever heard about was how my parents’ marriage went awry. I had to make sure to choose someone who would stick so that one day I would be a wife and mother. A woman was a woman only in relation to a man.

I was antsy. I went to therapy. I thought love meant sticking by somebody whenever things were difficult, no matter what. As an atheist, I needed something new to believe in, to ground me. Every session, instead of talking about myself, I’d be talking about my relationship. Or I’d be asking my therapist about hers, trying to read her face, picking apart her microexpressions. What is she thinking? I didn’t know what a good relationship looked like. Mine didn’t feel right, but I wasn’t sure if that was because I was young or wrong. "I feel like I'm constantly trying to apply permanence to changeable situations," I said.

Martha S. Cheng writes in "Ethos and Narrative in Online Educational Chat," "It is through the narrative of our lives that we maintain a sense of continuity or stability but also negotiate the events of our lives and social and cultural influences. Narrative is the nexus of identity" (198). As the narrative of my life was changing around me, I hadn't quite caught up to it. It felt as though my identity were unstable, in flux, and I couldn't place my feet.

_____

"Narrative is the nexus of identity."

(Cheng 198)

Sitting in my cubicle, I'd casually scan the perimeter, making sure my bosses couldn’t see my screen, and open A Practical Wedding. I read articles like “Why Do Feminists End Up Stuck in Gendered Marriages (and How Can We Avoid It)?” and “Do I Have Cold Feet or a Chemical Imbalance?” People like me were asking questions like me. People like me were commenting. People like me were replying to them. They were academics flung around the country and world. They were women struggling with gender roles. They were smart and funny and supportive. They were feminists and in relationships. They were my book heroines, all grown up and living in the real world. I read their words and inhabited them, imagined myself a writer/professor. The compulsive desire to get married turned into something a bit more nuanced. I started to understand that marriage could look different from the way I imagined it growing up. It could fit the person I was becoming—some day . . . maybe.

I broke up with my boyfriend, quit my job, and moved to Portland.

Hélène Cixous writes in “The Laugh of the Medusa,” “Woman must write her self: must write about women and bring women to writing, from which they have been driven away as violently as from their bodies—for the same reasons, by the same law, with the same fatal goal. Woman must put herself into the text—as into the world and into history—by her own movement" (875). Reading and writing gave me agency. Reading other women's writing gave me agency as well. I didn’t need to be in an unhappy relationship because my eggs were slowly dying and my siblings were all married and ten-year-old me thought I would be married by twenty-three, or at least on the way.

_____

“Woman must write her self: must write about women and bring women to writing, from which they have been driven away as violently as from their bodies—for the same reasons, by the same law, with the same fatal goal."

(Cixous 875)

When I moved to Portland, I started working at Hawthorne Books, the indie publisher responsible for my favorite memoir, The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch. In it, she traces her life from her early days with an abusive father and the freedom she finds in beginning to swim competitively, in using and strengthening her body to enact her own will. I saw myself in her descriptions of her troubled childhood, her page-consuming sexuality, her commitment to a haptic narrative that refused to kowtow to the sanitized modern-day Harlequin novels that had eaten up the women-focused literature sections of bookstores and best-of lists. In a supposedly postfeminist world, a corporeal and raw memoir written by a female felt like an act of defiance. The corporeal act of writing, of not only penning a memoir but also devoting her time to earning a PhD in English literature, became a model for me.

“Ask me about my life as a sexualized, gendered body, and I can tell you tales,” Yuknavitch writes. “Ask me about my writing, well, that’s a fierce private” (The Chronology of Water 181). Writing is a greater risk, a greater transgression of gender roles than having sex with men, women, and trans people, anecdotes she relays without pomp and circumstance. It is a greater transgression than openly discussing BDSM, rape, and molestation, which she does also. Writing is a risk because it disrupts the social order. It does not hide the female experience. It is not meek.

_____

“Ask me about my life as a sexualized, gendered body, and I can tell you tales .... Ask me about my writing, well, that’s a fierce private.”

(Yuknavitch, The Chronology of Water 181)

Sexuality complicates Yuknavitch. Desire complicates us all. As an adult, her sexuality becomes an extension of her inner turmoil. She throws her body and self-worth into others. Yuknavitch writes, “And when we’d fuck I’d climb on top of him and ride the art of his cock as hard as I could, wishing I was his guitar and not some fucked up damaged girl so that his fingers would strum me to death, strum me clean, strum me calm, strum me into a woman he’d write a song for” (The Chronology of Water 59). She describes sex with raw, vulgar language, concomitantly rejecting the sanitized language of traditional critical discourse. There is a sort of power in her self-deprecation, in presenting her sexuality tactilely. She does not reject her sexual past or former self. She simply presents her as is. No moral, no clean package for marketing purposes, just a sexual, physical being. Her sexuality makes her feel something, reattaches her emotions to her physical self. It spoke to me, like bell hooks speaks of Paulo Freire's work in Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. She writes, "Paulo was one of the thinkers whose work gave me a language" (hooks 46). Yuknavitch gave me a language to voice my sexualized and gendered experiences before I'd discovered academic theory.

Lidia’s sexuality allows her to be intimate with others without having to actually reveal her inner self. Her sister is the only person she is truly intimate with for the greater part of her life as a young adult, though she's sexually active. My sisters were my best friends and my role models, and still are. There is safety and tenderness in female relationships, separated from the issues of sex and dating and men. Lidia’s skin is a barrier between herself and the world, but by taking another’s skin into herself, she momentarily inhabits the space of another. Yuknavitch writes in "About a Boob Or The Hermeneutics of a Woman's Body," "The text is saying something about how an ordinary woman found a self by and through her own body. Between seeing and saying, a dialogic exists."

That's what I was doing in Portland, at night. I embraced my sexuality. I embraced men. I was pursuing my passions. I was pursuing men. I was single, but it was okay. I wasn’t looking for anyone to complete me anymore. I inhabited my mind and my body in a way I never had before. But I ended up feeling guilty because these men were not the people I saw myself marrying. I couldn't quite figure out the line between embracing my sexuality and my feminist self and also dating towards an end goal. I couldn't figure out if the guilt was coming from my Christian upbringing or if my sexuality was making me devalue myself or others.

Me

It was only in attending graduate school and beginning to write again that I achieved some peace, divorced from my relationship status. Well, also through daily yoga and swimming.

When I was packing to move to Michigan to attend graduate school, my mom told me, “You’ll meet someone when you go to grad school. A man. Not those boys you’ve been dating.”

Then when I got to graduate school and remained single: “Have you tried the library? Where do they all hang out? The science buildings? You’ll meet someone when you move back to California and start working.”

"I'm just going to write and read and focus on grad school," I told my mother. I had a long history of women to catch up on before I was going to think again about marriage, and a lot of writing to do.

And yet here I am, writing about marriage. When I set my hand to it, I felt nervous. I have a lot of qualms about the institution of marriage, although sharing my life with a partner is something I look forward to. I was afraid of feeding into my past obsession with relationships. It felt unscholarly, feminine. But Cixous’s "serious play of theory" (Rhodes), and Yuknavitch as her contemporary, posit that “feminine,” poetic lyricism and theory can go hand in hand. In fact, their writing styles subvert the cold, voiceless academic style of theory propounded by a patriarchal, colonial system.

Writing about marriage, I've learned, is allowing me to process the upbringing I had. I wanted to write about the way my sisters and I learned femininity from my mom, from each other, from our friends, and from our society. I was afraid of writing something too harsh towards all of them, something that blamed them for my previous obsession with marriage and relationships. But actually, in interviewing all of them and writing about it, I've experienced forgiveness for them and for myself.

From left to right: Thea, her son Ayden, me, Talia, my mom Ilona—all grown up

The interviews morphed from discussions about gender to our relationships, mostly my mother's relationship to us and to my father. I had a list of questions, but quickly left them for a more grounded-theory approach, allowing my mom and sisters to mostly guide the conversation. At first, I kept trying to pull a narrative thread from them, to bring it back to the topic I wanted to write about, but our conversations would not obey me. How could we move on to other topics when eighteen years on, we're still not over my parents' divorce? How could I not be obsessed with marriage when its dissolution still impacts my life?

While interviewing my mother, I could see the strides she has made as a partner, mother, and human. I could also tell she was trying to be very progressive and even-keeled in her responses regarding my marital status, more so than in her phone conversations with me. She knew she was on video. It is a strange thing to interview family members, to know so intimately their every expression. My mother has not remarried, and she has not forgiven my father for their divorce, but she has gleaned meaning from it. I think, in some way, if my siblings and I can have happy relationships, her marriage can still hold meaning. So she continues to ask me, as she always does a few weeks into me seeing a new guy, "Is he The One?" "I don't know yet," I always respond. I don't tell her that I don't believe in the idea.

My sister Talia got married recently. Each relative who came up to me did not ask me about how graduate school was going or how teaching was. They all asked me, "When are you getting married?" I would imagine that, by 2017, a woman's worth would be tied to other things than marriage. Maybe my Hungarian-Romanian and Irish-American family is old-fashioned, but also maybe this root-searching and experience-mining will be of some use to you, dear reader.

By feeling the societal and familial pressure to be married all throughout my life, so much of my brainspace was tied up with thinking about myself in relation to men.

Don't misunderstand me, romantic relationships are important. Essential. But they do not total my worth. They do not total a woman's worth. Of course, I am not an island. Parts of me and my brain are my sisters, and my mother, and my mentors, even my ex-boyfriends, and while we're at it, the whole human race.

By exploring why I'm fascinated by marriage and feminist theory, I had to go back to the root. My roots. I had to think about my past and ask my sisters and my mom for their versions. Then I had to filter all those inputs through feminist and rhetorical theory, and other memoirs.

Stories are the way we make meaning of the world, and sharing those stories are how we all learn.

***

A note: In an earlier part of this piece, I am somewhat explicit regarding my sexuality. It was recommended to me to remove this section. However, after much thought, I have very purposefully left it in. As Jacqueline Rhodes said, "As a feminist, my body is already on the line, so why not put it in?"

Works Cited

Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute, 1999.

“About APW.” A Practical Wedding, 2008, https://apracticalwedding.com/about-apw/. Accessed 9 Nov. 2018.

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge, 2006.

Cheng, Martha Sylvia. “Ethos and Narrative in Online Educational Chat.” Rhetoric in Detail, edited by Barbara Johnstone and Christopher Eisenhart, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2008, pp. 195-226.

Cixous, Hélène. “The Laugh of the Medusa.” Signs, vol. 1, no. 4, 1976, pp. 875-893.

Estrem, Heidi. “Writing is a Knowledge-Making Activity.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State UP, 2015, p. 19.

Harding, Lindsey. “Super Mom in a Box.” Harlot, no. 12, 2014, http://harlotofthearts.org/index.php/harlot/article/view/197. Accessed 9 Nov. 2018.

hooks, bell. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. Routledge, 1994.

Kirsch, Gesa E., and Liz Rohan, editors. Beyond the Archives: Research as a Lived Process. Southern Illinois UP, 2008.

Rhodes, Jacqueline. “Techne, Rhizomes, and the Authored Self.” Michigan State University, 8 Feb. 2016, MSU Writing Center, East Lansing, MI. Research presentation.

Salamon, Gayle. Assuming a Body: Transgender and Rhetorics of Materiality. Columbia UP, 2010.

Sands, R. G. "Narrative Analysis: A Feminist Approach." The Qualitative Research Experience, edited by D. K. Padgett, Wadsworth/Thomson Learning, 2004, pp. 48-78.

Yuknavitch, Lidia. “About a Boob Or The Hermeneutics of a Woman’s Body.” The Rumpus, 16 Feb. 2011, https://therumpus.net/2011/02/about-a-boob-or-the-hermeneutics-of-a-womans-body/. Accessed 9 Nov. 2018.

---. The Chronology of Water. Hawthorne Books, 2010.

Hidalgo | Chambers | Hutchinson

Shade-Johnson | Brentnell | Leger

Braude | Sweo | Nur Cooley

__________________________________

Intermezzo, 2018